As far back as we can go, they are there, waiting for us. 40,000 years ago, or so, a figure known today as the Löwenmensch, or “lion-man”, was carved from a mammoth’s tusk in the Swabian Jura, combining features of human and beast. In the oldest written tale, the 4,000-year-old Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh, the eponymous hero confronts the forest guardian Humbaba the Terrible, a tusked giant born from a mountain, whose “speech is fire, and his breath is death!”

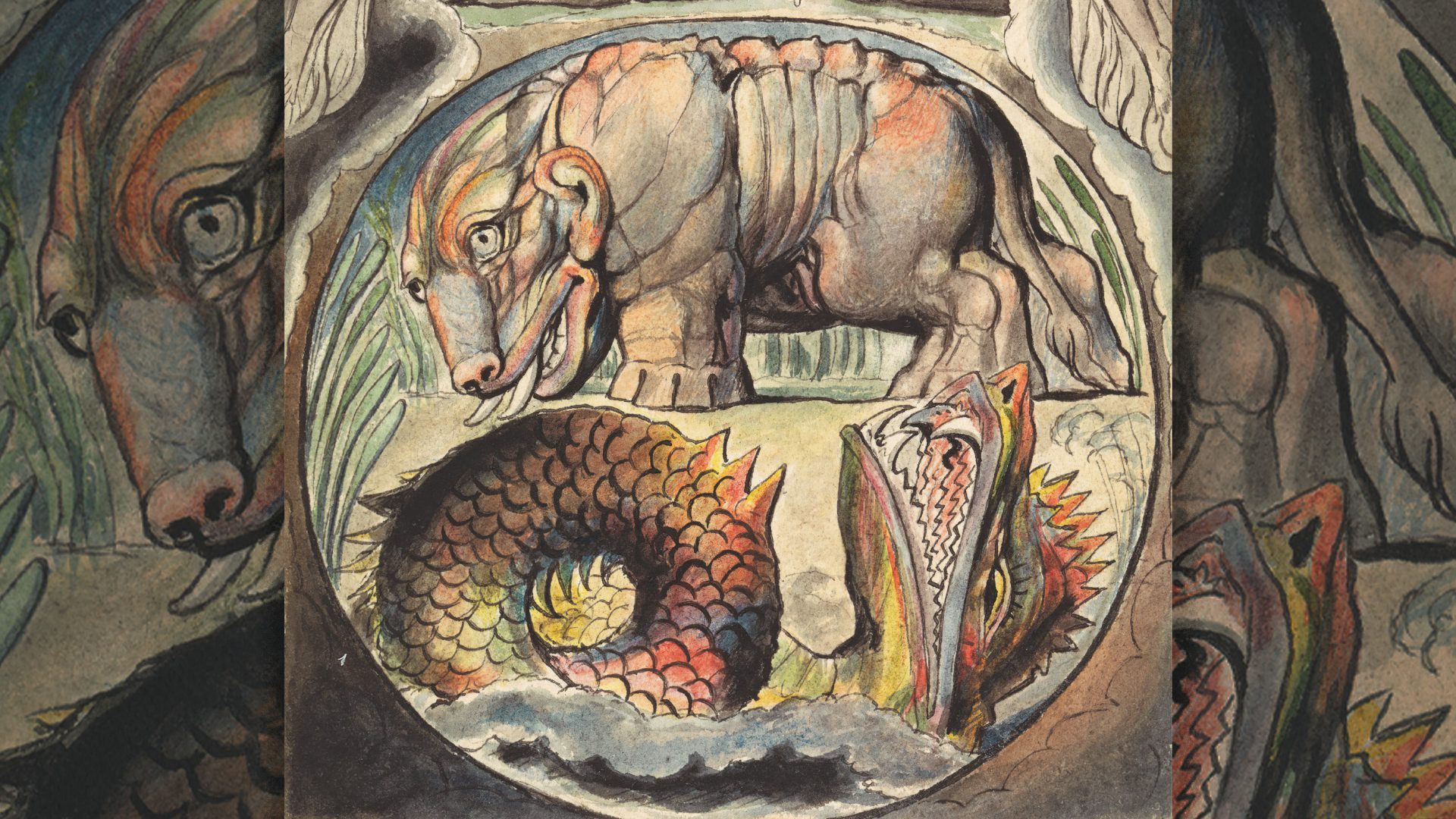

The Bible tells of Behemoth, the chaos-monster at the beginning of creation. Browse the pages of The Tibetan Book of the Dead and you’ll come across Wrathful Deities with the heads of wild beasts, garlands of snakes, and corpses over their shoulders, stirring the cycle of existence with their lions’ manes and bulging eyes.

The stories of the ancient world can be so boggy, with their arcane rites and auguries, baffling hierarchies and obsession with honour; it’s a challenge to find an accessible entry point. What guides us in, again and again, are the monsters: Odysseus and his crew trying not to get eaten by the Cyclops, the Hindu hero Rama and his monkey army battling demonic Rakshasas, the great northern strongman Beowulf ripping the clawed arm from the fen beast Grendel’s shoulder. A few things may have changed over the millennia, but our fascination for monsters isn’t one of them.

What is different, however, is the way that we perceive the monsters. For the people who told those long-ago tales, they were more than mere fodder for heroic deeds. They were palpable threats to life and (even more worryingly) the afterlife, liable at any moment to tear through the flimsy barrier between our world and theirs. The earliest monsters were scarcely distinguishable from the gods — terrifying beings that decided when avalanches fell and thunder roared and floods drowned the early settlements.

Four thousand years ago, pregnant women in Mesopotamia feared a visit from Lamashtu, a skull-breasted figure with donkey’s ears, a bird’s talons, and a mantle of coarse black hair, whose companions included a hound with red and green eyes and a fourteen-foot jackal. Lamashtu was the daughter of the Sun God, not some wily outcast but a representative of the powers-that-be, and if she took against you, she would tear your newborn baby out of your arms, to suck its blood and chew on its bones. Like many of the gods that emerged across the Red Sea in ancient Egypt — jackal-headed, lion-headed, falcon-headed, guardians of mummies, night spirits, or deities of disease — Lamashtu was a god and a monster, appeased with ritual sacrifices and prayers.

But time slowly prised gods and monsters apart. Animism (the belief that spirits reside in all things) gave way to theism (the belief that power over all is the preserve of a few divine beings, or a single deity in the case of monotheism). Monster-gods were shunned in favour of gods made (to flip the biblical line) in humanity’s image. Even where the monster-gods were retained, they tended to slip down the hierarchy. The leading gods became ever more human-like, reflecting the soaring confidence of human societies.

As for those fanged, clawed, beast-like gods, they tended to fall out of the pantheons, doomed to prowl the earth, demoted and decayed but retaining something of their old mystique, repurposed as vanquishable monsters for human heroes to hunt.

It was the gods that had changed. The monsters had always reflected our uneasy relationship with the wild places around us, our fear of what might lurk in the dark. When a retired warrior called Guthlac decided to devote his life to prayer in seventh-century Lincolnshire, he knew he would have to reckon with the “multitude of fiends”. Kneeling in his hermitage, he was ransacked by “the loathsome clutches of spirits, wretched and wracking… fierce to rush upon him with greedy grasp”.

The monsters were existential torments, the old deities that men and women used to worship, but they were also physical. Mired in dirty water and swarming with insects, the fens of Lincolnshire were no place for the healthy. Dark stories hovered, incessant as the midges.

Roaring out of hostile environments as well as our own agitated psyches, monsters embody what unsettles us. Which is why they are so easily projected onto “others”: other races, other belief systems, other ways of living. Mediaeval writers and illustrators filled vast tracts of terra incognita, the yet-to-be-discovered world, with monstrous races – dog-headed Cynocephali, Blemmyes with their heads in their chests, Sciapods lying in the sun under a single clubbed foot; dragons, mer-people, wave-sweeping leviathans. Here be monsters: kicked out of the heavens, they were roiling around us on earth, and if we pointed our spears at them, we had a decent chance of laying them low. They represented the fringes, wherever civilisation had yet to assert control. And they represented other civilisations too – the ones our own had yet to conquer.

But if the wild places harboured many of the monsters of folk belief, others poured out of an even more unsettling realm. In 1642, the residents of Edgehill in Warwickshire reported a spectre of “incorporeall souldiers”, and so many testified to these apparitions that a report was commissioned by King Charles I.

Visions of the dead have been cited throughout history, manifesting as ghosts, vampires, and other eerie apparitions. They feature in many of the most troubling tales ever told, evoking our apprehension as well as our curiosity about the Great Hereafter.

Wild places and the realm of the dead: most folk monsters can be assigned to one or the other. But another, even more disturbing category, is required. Back in biblical times, King Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon suffered from a curse: “his hair grew like the feathers of an eagle and his nails like the claws of a bird”. He was a theriomorph, like the werewolves and other shapeshifters of more recent tales. There’s nothing freakier than the fear of turning into a monster. Except, perhaps, when the monsters turn into us.

Monsters flourished for millennia, pressing against the psyches of every stratum of society, from rulers like Nebuchadnezzar to the shepherds of Edgehill. But time caught up with them at last. The Age of Discovery revealed a lot, but it didn’t produce any dog-headed men or sunbathing Sciapods. Instead of nations of weird beings, monsters were reduced to isolated individuals with genetic anomalies: sufferers of elephantiasis, Proteus syndrome, hypertrichosis. Crowds may have gawked, but fear shrank as humanity’s knowledge and power increased. With the Age of Science, the traditional monsters found themselves against an insuperable barrier, dismissed from reality and excluded from scientific taxonomies. They were confined to the zone of storytelling, glamorous after-images of dying or disempowered cultures. Some of the most powerful manifestations of monsters exist in this limbo state, representing historical memories of times long past, emotional connections with periods of seismic change and traumatic loss.

But the world keeps turning, and in the industrialised world, a new perception of monsters emerged. In a world less and less convinced of their existence, they became monetised spectacles, marshalled for a rapidly increasing range of mass media. From macabre bloodsuckers in penny dreadfuls to stop-motion, rubber-suited, or (latterly) CGI movie behemoths, monsters have taken pride of place in commercial storytelling.

This doesn’t mean the old fears have been fully suppressed (or, at least, in being suppressed, they still have a knack for finding outlets). In an irony that says much about the twisty path of the monster story, science – which had done so much to smother the old beliefs – became the most fertile source of our modern fears, and inspiration for new hordes.

Now, instead of being spawned by gods or magic spells, monsters draw their power from electrolysis, poisonous chemicals, neutron radiation, fossil-fuel extraction, cloning technology; or they travel across the stars, alerted to our planet by the signals we’re relentlessly broadcasting. Punishments for human hubris, these new monsters transform our scientific achievements into visions of the apocalypse that will eventually engulf us.

Monsterland: A Journey Around the World’s Dark Imagination by Nicholas Jubber is published by Scribe (£20)