To invent the ship, wrote the French philosopher Paul Virilio, is also to invent the shipwreck. Every technological innovation brings both gains and unintended losses – and one of the great challenges for modern governments is to help maximise the first while mitigating the second.

From the cutting edge of scientific research to self-driving vehicles, from new human-machine interfaces to the automation of swathes of drudgery, technologies like artificial intelligence – which Tony Blair is urging the new government in No 10 to exploit – promise vast benefits to humanity. But they also offer a pointed case study in the risks of technological overreach. By the end of 2024, the greatest number of people in history will have participated in some kind of election (over four billion people, half of humanity). There has never been more information at citizens’ fingertips – or more opportunities for manipulation and misinformation.

As a species, our capacity to analyse and transform the world around us is unprecedented. But so too is the concentration of power in the hands of some individuals and corporations, the degradation of our environment, and the severity of the long-term challenges we face.

Amid all this, what can and should the new government look to do? In November 2023, Britain hosted an AI Safety Summit devoted to some of the greatest existential questions in the realm of technology. Will the rise of super-powerful machines pose a risk to the very survival of humanity? Or might they solve all our problems at a stroke? Figures like Elon Musk dominated headlines, warning of the arrival of “something that’s going to be far more intelligent than us”.

But representatives of most of civil society were absent, as were the voices of citizens concerned not so much by hypothetical super-intelligences as by the prospect of being made redundant, of suffering discrimination or exploitation thanks to the biases baked into algorithms, or of seeing their online activities tracked and analysed with a minimum of transparency.

It is, I would suggest, these everyday hazards and frustrations – not the science fiction scenarios beloved of futurologists – that present the greatest challenge and opportunity when it comes to technology, and the new occupant of No 10 must keep this in mind.

To live in a 21st-century society is to possess extraordinary opportunities for learning, communicating and thriving. But it’s also to inhabit an age where failures of technological design, foresight and deployment can engender a host of harms – and where accountability and transparency are harder than ever to enforce.

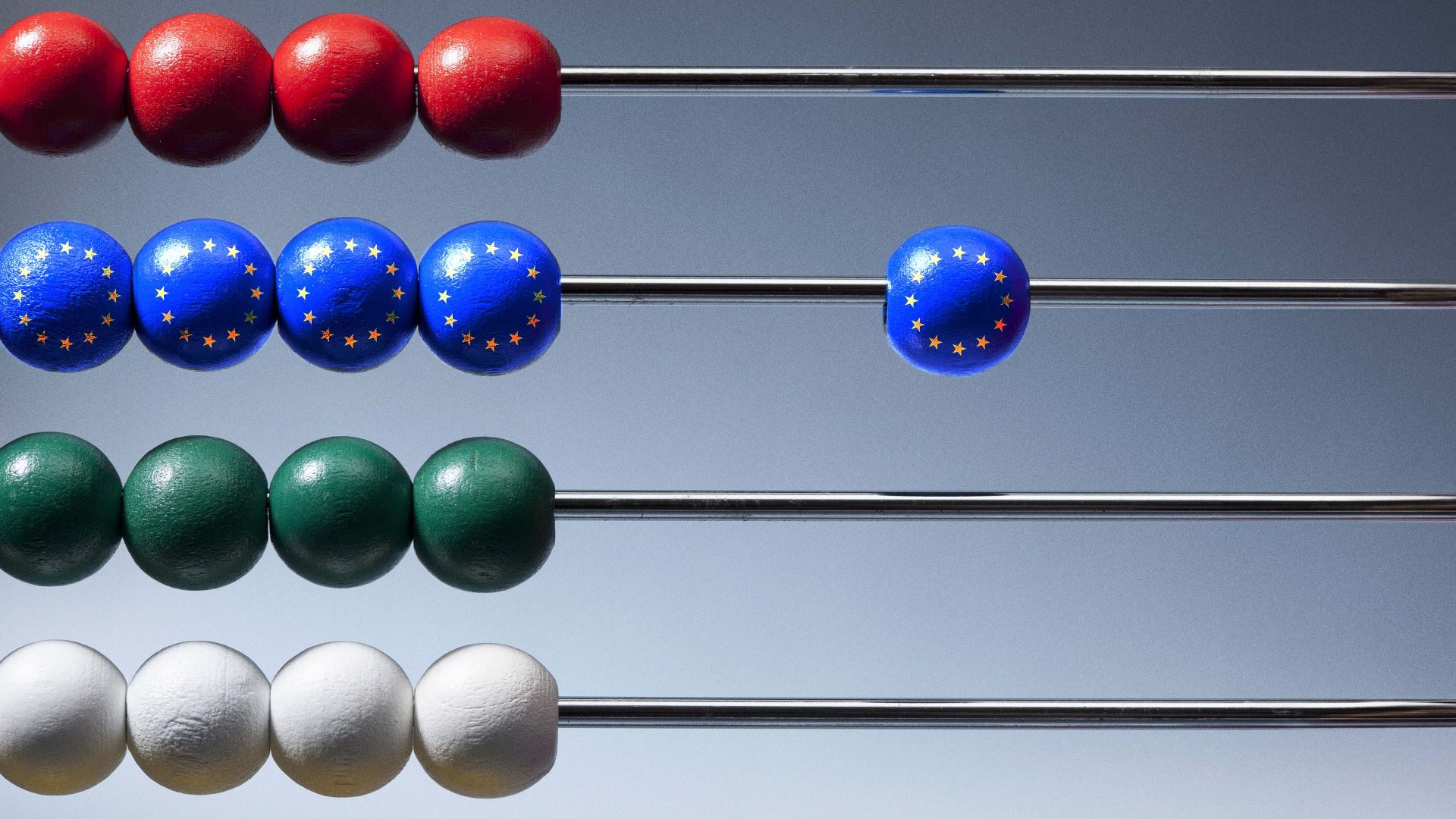

One of the boldest recent attempts to address such issues is the EU’s AI Act, passed in March 2024 after months of debate and lobbying, which attempts to create a common regulatory and legal framework for the deployment of AI. It is, to say the least, an ambitious piece of legislation, aimed at ensuring any AI systems deployed in Europe are trustworthy, fair and aligned with democratic values.

To this end, it has a dual focus. On the one hand, it seeks to limit the use of high-risk technologies that might cause harm, such as public facial recognition systems and forms of biometric categorisation. On the other hand, it enshrines in law a range of principles intended to align AI with fundamental rights like non-discrimination, dignity and privacy. These principles include algorithmic explainability, transparency, and safeguarding against bias, as well as environmental sustainability, resilience against manipulation and human oversight. The effects of the act are likely to be considerable.

It’s a striking, principled attempt to set a global precedent, and this boldness may prove both its greatest strength and its greatest weakness. It has placed the ethics of AI firmly on the international agenda, and offered a thoughtful vision of what it might mean for technology to serve rather than subvert democracy.

At the same time, however, high-level judgments such as what constitutes a “high-risk” system come with ambiguities that may lead to years of legal wrangling, while the demands its ambitions will make upon regulatory bodies are substantial.

For some critics, moreover, the very scale of its requirements seems likely to stifle innovation, leaving the EU at a disadvantage when it comes to attracting innovation and talent.

What can the new PM learn from this? Perhaps the greatest lesson to be taken from legislative efforts in the EU and elsewhere is that, despite the claims of promoters, too great a focus on cutting-edge systems like AI is itself problematic when it comes to making the most of technology – while the most important principles of all are inextricably entwined with other aspects of society.

Consider one of the most tragically impactful technological stories of the last few years: the Horizon IT scandal at the Post Office. Its details have been endlessly discussed, but their outline bears repeating.

In 1999, the UK Post Office introduced a new IT system called Horizon to centralise and automate accounting across its thousands of branches. However, the system was riddled with bugs and errors that led to mysterious accounting shortfalls. Rather than investigating and fixing these problems, the Post Office blamed them on sub-postmasters, ruthlessly prosecuting more than 700 for theft and false accounting over the next 15 years.

It also went to extreme lengths to cover up the truth. In 2009, Computer Weekly broke the story, leading to sub-postmasters forming a campaign group. In 2019, after a long legal battle, the true scale of the scandal finally became clear – although it took a 2024 television drama for the victims’ exoneration to become a government priority.

To borrow a phrase from the cultural anthropologist Madeleine Clare Elish, the sub-postmasters in effect acted as a “moral crumple zone” throughout this sorry sequence of events. Where the crumple zone in a car protects its human occupants, a moral crumple zone consists of humans taking the blame in order to protect a technological system.

The Post Office refused to consider the possibility that Horizon was flawed. Seduced by the apparent ease and infallibility of a cutting-edge technology, it proceeded on the basis that any errors must be the result of human incompetence or malice – and that its task was to protect the integrity of the system at all costs (not to mention the careers and consciences of those who had wedded their fates to it).

At play in the Horizon scandal were the corrupting effects of two all-too-common trends in public-sector technologies: the assumption of an automated system’s infallibility, and indifference towards the real-world experiences of its users. The lessons to be drawn here go far beyond the Post Office, and they emphasise the importance of a principle the UK government’s own digital services were founded upon in the early 2000s. Good design begins with identifying user needs. If you don’t understand these, you won’t be able to build something that works. And if you don’t talk to people, listen to what they say and follow the data where it leads, your understanding will never be adequate.

The best way to pursue grand technological purposes, in other words, may be a form of digital localism that attends to experiences, needs and concerns on a granular level, and that seeks to empower citizens rather than imposing on them from on high. And achieving this means investing in the kind of infrastructure that lets citizens engage meaningfully with the technologies shaping their lives: well-resourced libraries, universal access to the internet and digital devices, a thriving landscape of expert advice and guidance, genuine powers of democratic appeal.

It’s initiatives like these that make principles such as transparency and accountability powerful in practice; while it’s a failure to invest in this kind of support that is most likely to make citizens vulnerable to misinformation, manipulation and disengagement.

In this sense, the principle of keeping humans meaningfully in the loop applies to far more than AI. It’s also a golden rule of governance – and one that dovetails with the immense good that can flow from a skilled, dynamic digital economy, if it’s supplied with the right incentives and a principled vision for the future.

Beneath the hype and fairytales surrounding future technologies, then, lie real lives, harms and opportunities: inequalities and exclusions embedded in data; exploitative and inadequate forms of automation; inscrutable and unaccountable manipulators and rent-seekers. And the solution isn’t more storytelling, or the hope that fine principles will by themselves set people free.

Rather, technology is at root about making stuff that works: and, specifically, that works for citizens; that addresses their needs and empowers them to find fulfilment and create value; that delivers what it claims to do, without extracting a hidden toll; that is reliable, secure and sufficiently scrutinised, with robust avenues for redress. After over a decade of painful under-investment in the infrastructures that underlie all of these things – access to tools, training, support, education, consultation, investment and regulatory clarity – the UK has an opportunity now to lead the world once again. But only if its new government can think big enough to focus on the small picture.

Tom Chatfield is an author and tech philosopher. His latest book, Wise Animals (Picador), explores the co-evolution of humanity and technology