Amiens railway station, late afternoon on 23rd November 1889. An elderly couple on the platform peer anxiously up the line into the gloaming. They’ve come to meet someone from a train that should have arrived a few minutes

earlier and are concerned about the consequences of a delay for a guest already on a tight schedule.

The man, his long white beard spilling down the front of his overcoat, spots a light in the distance. At the sound of a whistle, the couple look at each other and exhale with relief. The train hisses to a halt in front of them, carriage doors open along its length and from one of them emerges a young woman in a long coat carrying a small carpet-bag. Jules Verne steps forward, holds out his hand and introduces himself to Nellie Bly.

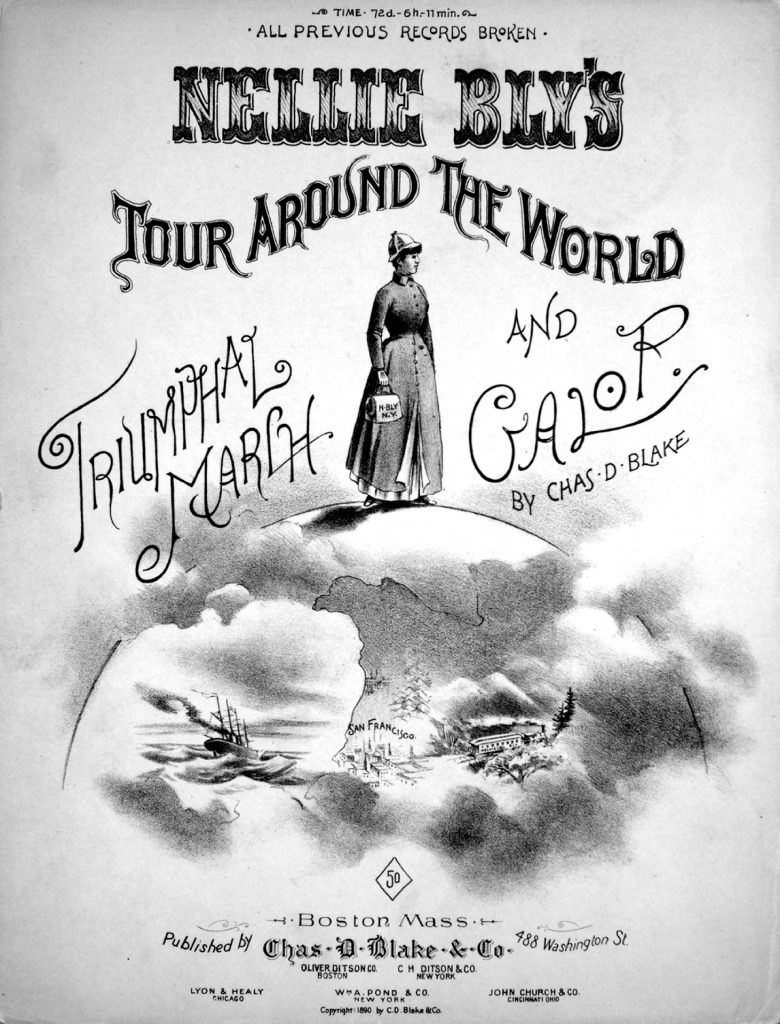

The current BBC adaptation of Around the World in 80 Days, loosely based on Verne’s original text, arrives 150 years after the classic novel’s publication in France in 1872, but another significant anniversary related to the book falls next week. January 27 marks the centenary of the death of Nellie Bly, the first person to prove that Phileas Fogg’s fictional global circumnavigation could not only be done, but done faster and by a young woman travelling alone. Indeed, Bly would lop off a week from Fogg’s literary achievement, completing her journey in just 72 days, 6 hours and 11 minutes.

Unlike Verne’s creation, Bly was no wealthy idler roused from his armchair only by a lucrative wager. A record-breaking circumnavigation was just one remarkable achievement of a pioneering investigative journalist, novelist and, later in life, industrialist.

Her epic voyage was a commission from the New York World, owned by Joseph Pulitzer who, when Bly appeared in front of him waving a copy of one of the most popular fiction titles of the age insisting she could do it faster, recognised a huge publicity opportunity when he saw one, even if John Cockerill, the World’s managing editor, had taken more convincing.

“It’s impossible,” he insisted. “You are a woman and would need a protector, and even if it were possible for you to travel alone you would need to carry so much baggage that it would detain you in making rapid changes. No one but a man can do this.”

Bly had heard that old chestnut before. “Very well,” she said. “Start the man and I’ll start the same day for some other newspaper and beat him.”

She departed on November 14, 1889, carrying a bag containing just “two travelling caps, three veils, a pair of slippers, toilet articles, an inkstand, pens, pencils, paper, pins, needles, thread, a dressing gown, a tennis blazer, a small flask, a drinking cup, a few changes of underwear, handkerchiefs and a jar of cold cream”. She decided, despite advice, not to take a revolver.

“I had such a strong belief in the world’s greeting me as I greeted it that I refused to arm myself,” she wrote.

After a stormy Atlantic crossing, Bly arrived in England to an invitation from Verne to call upon him as she passed through France, hence that unusual juxtaposition of life and art on the platform at Amiens.

“Jules Verne’s bright eyes beamed on me with interest and kindliness, and Mme. Verne greeted me with the cordiality of a cherished friend and before I had been many minutes in their company they had won my everlasting respect and devotion,” wrote Bly in the bestselling account of her journey called, inevitably, Around the World in 72 Days.

“My line of travel is from New York to London, then Calais, Brindisi, Port Said, Ismailia, Suez, Aden, Colombo, Penang, Singapore, Hong Kong, Yokohama, San Francisco, New York,” she told the novelist.

“Why do you not go to Bombay as my hero Phileas Fogg did?” he asked.

“Because I am more anxious to save time than a young widow,” Bly answered.

“You may save a young widower before you return,” smiled the novelist, a lame joke about Bly’s marital status that, again, she’d heard many times before.

“I smile with a superior knowledge, as women, fancy-free, always will at such insinuation,” she wrote.

A young woman travelling alone in 1889 was always likely to raise eyebrows. Bly fended off a number of approaches on her way across the Atlantic, shaking off one persistent suitor by hiding his wooden leg.

Even the president of the Royal Geographical Society, Sir Mountstuart Grant Duff, reacted to her achievement by hoping it might secure Bly “a good husband”. Such relentless chauvinism might have exhausted other women, but campaigning for women’s rights is what had fired her writing from the start.

Born Elizabeth Cochran in Pennsylvania in 1864, Bly’s career in journalism began in her late teens with an angry response to a piece in the local Pittsburgh Dispatch called “What Girls Are Good For” – marriage, motherhood and the kitchen was about the size of it – that impressed the editor so much he took her on as a reporter, bestowing the pen name Nellie Bly from the lyrics to a popular local song. From the beginning, Bly’s pen highlighted the parlous state of rights for women in 19th century America.

“Instead of gathering up the ‘real smart young men’,” she wrote in 1885, “gather up the real smart girls, pull them out of the mire, give them a shove up the ladder of life and be amply repaid both by their success and unforgetfulness of those that held out the helping hand.”

When the Dispatch tried to nudge her towards less contentious subjects like flower shows and dressmaking Bly upped sticks for New York and in 1887 secured a job with the World, throwing herself headlong into publicising the unfairness of women’s labour laws and how divorce settlements were slanted outrageously towards men, as well as penning courageous undercover exposés.

Prior to her Vernean odyssey, Bly was best known for hoodwinking doctors into committing her to the Blackwell’s Island Insane Asylum for Women, about which she wrote a series of articles later published in book form as Ten Days in a Madhouse.

“What, excepting torture, would produce insanity quicker than this treatment?” she asked of beatings, ice baths and mouldy food, a question that appalled the nation enough to prompt major institutional change.

Back at Amiens, she waved goodbye to the Vernes from the Brindisi mail train, taking with her the author’s cautious best wishes.

“‘If you do it in 79 days I shall applaud with both hands,’ Jules Verne said, and then I knew he doubted the possibility of my doing it in 75, as I had promised,” she wrote.

After a series of adventures by train, ship, sampan, gharry, catamaran, donkey, barouche and at least one cart pulled by a bullock, Bly docked at San

Francisco on January 21, 1890. She arrived two days behind schedule, prompting Pulitzer to charter a train to ensure his protégé arrived in New York as planned.

When Bly stepped onto the platform at Jersey City in the late afternoon of 25 January, among the crowd of 15,000 to greet her were three official timekeepers from local athletics clubs clicking their stopwatches to confirm her finishing time. Pulitzer had maintained a fervent interest in a journey from which Bly could only occasionally file copy by running a sweepstake on how long the odyssey would take. More than a million people entered.

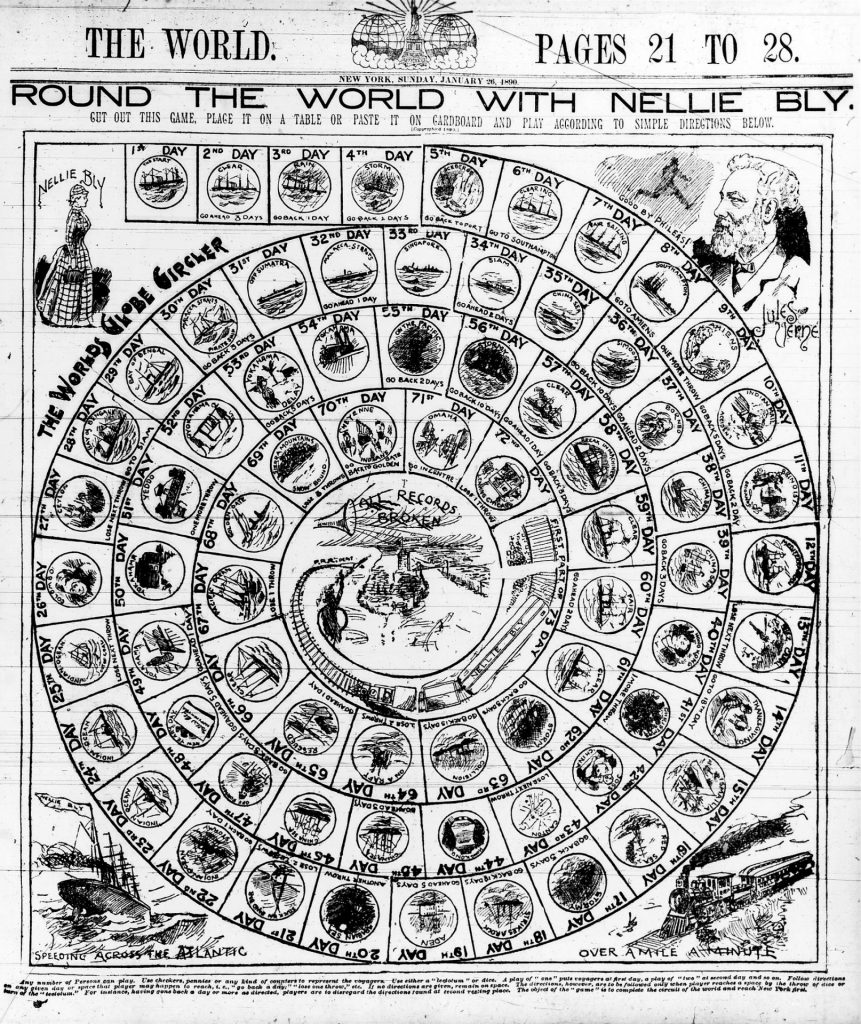

Despite her new-found celebrity – her voyage was turned into a popular

board game and she advertised everything from horse feed to Kodak cameras – Bly left journalism to write fiction, earning a whopping $15,000 a year penning serials for the New York Family Story Paper that became a dozen bestselling novels. In 1895 at the age of 31, she married industrialist Robert Seaman, 42 years her senior, taking over his steel barrel-making

company on his death a decade later, and setting about improving working

conditions and opening libraries and gymnasiums for employees.

When the business failed in the run-up to the First World War, 50-year-old Bly returned to journalism, travelling to Europe as a war correspondent for the New York Evening Journal. She returned to the US in failing health in 1919 and died in New York on January 27, 1922 at the age of 57.

While obituaries filled newspapers across the world, Nellie Bly is no longer a household name. The centenary of her death will likely pass largely unnoticed but at least the sesquicentennial of Verne’s novel gives us an opportunity to remember the woman who became the closest we ever had to a real-life Phileas Fogg.

The BBC adaptation of Verne’s masterpiece veers significantly from the original, not least in how the book’s Detective Fix of Scotland Yard is supplanted by Abigail Fix, played by Leonie Benesch. An independent young woman journalist joining Fogg and Passepartout on their voyage around the world is a perfect nod to an exceptional woman who, 17 years after Fogg departed the Reform Club, became the first to prove it really was possible to go around the world in 80 days.