It’s a haunting image and it has branded itself on the British consciousness over the past two weeks: Richard Ratcliffe on hunger strike outside the Foreign Office in London, as he begs the UK government to pay a decades-old debt so that his wife, mother to their seven-year-old daughter, can come home from Iran, where she has been detained on spurious charges for more than five years.

As each day has passed, pushing Ratcliffe closer and closer to physical collapse, anger has mounted and the calls have grown louder for Boris Johnson’s government to act urgently to end the family’s ordeal and bring Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe home. Although the fault lies with Iran, the solution is within our government’s grasp. But with foreign secretary Liz Truss tweeting photographs of herself in the jungles of Malaysia this week, there are few signs it is listening.

And this is why Ratcliffe feels compelled to act, forced to put his body on the line for the second time in two years as he campaigns for 43-year-old Nazanin – a British citizen with dual Iranian nationality – in the face of what he calls a failure of UK diplomacy that is robbing himself, Nazanin and their daughter Gabriella of years of their lives.

“It’s a way of putting pressure on the British government,” he says when I visit him on day 11 of his protest. “The threat is there and (Iran) will follow through if they think things are too quiet. So (my hunger strike) is a way of keeping Nazanin safe. That’s in my head. I’m not sure Nazanin’s quite so confident but I thought if we didn’t do something she’d be in prison by the end of the month, certainly by Christmas. And hopefully now, we’ll buy some time. It won’t buy endless time but it will buy some time.”

Iran has linked Nazanin’s detention to a decades-old £400million debt owed by Britain to Iran for tanks that were never delivered by the International Military Service, a now defunct arm of the Ministry of Defence. An international court has ruled that the money should be paid, the cash is in an escrow account and yet the debt is still outstanding, with the UK arguing that sanctions against Iran make payment tricky.

Ratcliffe says sanctions are no longer an issue and the money can, and should, be paid.

“Fundamentally, Nazanin is innocent. The British government took a very long time to acknowledge that innocence, a very long time to actually make any strong statements and has made no actions to challenge Iran on holding her hostage. They’ve also not given Iran what they’re asking for, which is also very simple and clear, unpalatable but clear.

“Ultimately from the Iranian perspective, it’s their money, they went to court and they want their money,” he said. “It’s a cold policy choice to leave us languishing in that context.”

He eases himself on to the hot water bottle his sister has placed on the seat of a canvas camping chair and starts to break down the stages of a hunger strike.

“The first two days you get hungry then that goes away and your metabolism slows down and your body starts eating itself up,” he says. “What that means is it’s hard to keep warm. I feel the cold most.”

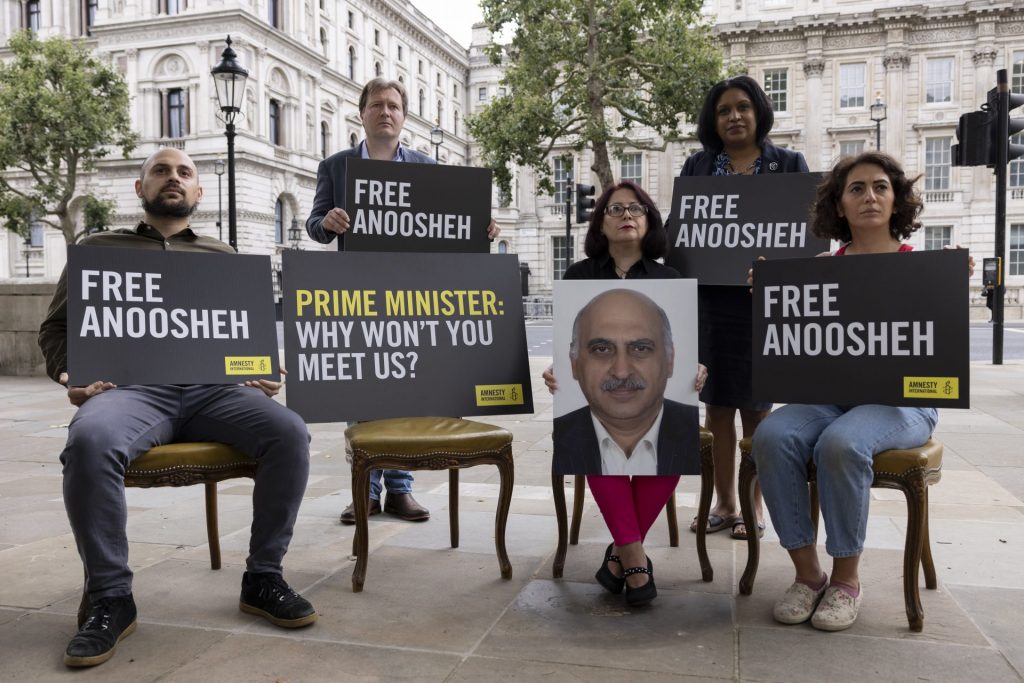

Ratcliffe is not alone in his despair. Also on the pavement on that cold November morning when I visit, stamping his chilled feet after spending a night in one of the pop-up tents is Aryan Ashoori, the son of Anoosheh Ashoori, a 67-year-old British-Iranian dual national like Nazanin, who has been detained in Iran since 2017 on accusations of spying, charges he denies. Aryan is not on hunger strike – his jailed father said no to that idea – but the two families have made common cause in their attempts to get their loved ones home.

Ratcliffe decided to embark on this second hunger strike after he met Truss the day after Nazanin’s appeal against a second jail term failed in October. Truss said the government would act if and when Nazanin was put back in jail because that would be a red line for them. But Ratcliffe has seen the red lines shift before and he says the endless legal to-and-fro over the unpaid money is just a fig leaf for what he calls “political resistance”.

But the Foreign Office does not seem inclined to budge. Asked this week what practical measures the UK would take if Nazanin was sent back to jail, it said in a statement: “Iran’s decision to proceed with these baseless charges against Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe is an appalling continuation of the cruel ordeal she is going through. Instead of threatening to return Nazanin to prison, Iran must release her permanently so she can return home. We are doing all we can to help Nazanin get home to her young daughter and family and we will continue to press Iran on this point.”

Iran is still insisting on the money though. On November 8, foreign minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian tweeted: “Useful phone call with UK FM.

Discussed bilaterals incl consular issues; and regional topics. Urged repayment of long overdue UK debt to Iran. On Vienna talks, reiterated return by other parties to full impl of obligations, lifting of all sanctions and verification and guarantees.”

Nobody denies Iran’s ultimate responsibility for this callous policy of seizing British citizens and other foreign nationals to be used as political pawns but the families and observers say the UK has also failed to show real commitment to bringing its citizens home.

“I am shocked that the Foreign Office under different prime ministers has not shown diplomatic muscle, creativity or the ability to make this a top priority,” said Hadi Ghaemi, executive director of New York-based advocacy group, the Center for Human Rights in Iran. “It is really a failure of the UK foreign policy establishment that has been in power over the past five years… They don’t seem to see this as a priority and it is very disheartening.”

What Ratcliffe also calls a failure of diplomacy and campaigning reached its nadir in 2017 when then foreign minister Boris Johnson claimed that Nazanin had been training journalists in Iran, remarks that Ratcliffe said enabled a propaganda campaign against her and were used to justify a second court case. Johnson was forced to apologise.

Nazanin was arrested in 2016 while visiting her parents in Iran with the couple’s then two-year-old daughter. She was accused of plotting against the regime and sentenced to five years in jail. She served out her time, enduring interrogations, months of solitary confinement, hunger strikes, ill-health and intense stress.

In March 2020, she was released from Tehran’s notorious Evin prison because of the Covid pandemic and served her final year under house arrest at her parents’ home but she faces the prospect of a second prison term after losing an appeal in mid-October against a second set of charges, which she also denies. She’s now waiting in her mother’s house in Tehran for the phone call that could summon her back to prison for another year.

Nazanin and Anoosheh are victims of what Anoosheh, who tried to take his own life three times in prison but who now has found the strength to fight for his freedom, calls the “anti-lottery” of life. Activists, analysts and observers call it hostage diplomacy – a uniquely cruel political strategy that makes losers of all involved.

The fate of unjustly detained dual and foreign nationals is not just linked to the British debt. Analysts also say there is a connection to the stop-start negotiations to revive the 2015 nuclear deal, or Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), which Donald Trump withdrew from in 2018, reimposing sanctions on Iran and prompting Tehran to breach mandated limits on uranium enrichment the following year.

The talks have been stalled since the summer to allow Iran’s new regime, led by hardline President Ebrahim Raisi, to review its negotiating strategy. They are due to resume at the end of this month.

“The reality is that unfortunately, these individuals are pawns in a much bigger geopolitical game that is completely out of their control,” said Ali Vaez, senior advisor and Iran project director at the International Crisis Group.

He said the British negotiators came close to a deal on freeing Nazanin, Anoosheh and other dual nationals this summer but talks fell apart when the Vienna negotiations on the JCPOA stalled because of the Iranian political transition.

“It has unfortunately become a Catch-22 in the sense that while both sides publicly say humanitarian and consular discussions should be separate from nuclear discussions in practice, because there is a financial element attached to the whole package, it’s hard to imagine that deal going through in the absence of sanctions relief,” he said.

Sherry Izadi, Anoosheh’s wife, says then foreign secretary Dominic Raab confirmed in the summer that a deal had nearly been secured. “He told us we came this close, he actually made this gesture,” she says, holding her thumb and index finger together as we speak over Zoom. Raab implied that the deal broke down over the fate of Morad Tahbaz, a businessman and wildlife conservationist with UK, US and Iranian nationality.

“The deal would have involved the debt payment and, I’m guessing, the prisoner swaps, which is where the American angle came in. The Iranians said it was the Americans who broke the deal. Dominic Raab told us it was the Iranians who asked too much so the deal broke down,” she said.

Vaez said this linking of American and British detainees could complicate matters, making it almost impossible for Britain to resolve the issue alone.

Sherry’s priority is to try to get diplomatic protection for Anoosheh as this would, in theory, elevate his case to a state dispute. Nazanin was granted this status in 2019. She applied for diplomatic protection in April but the Foreign Office has not yet made a decision and she fears they will say it will not help Anoosheh’s case.

“Anoosheh is paying for having a British passport,” she says. “We’ve been through all this pain because we have a British passport and the very people who are responsible for that passport are not doing anything,” she said.

Behind the anger is concern for her husband. “To say I admire him would be a massive understatement because he’s mentally and physically held up pretty well.”

But she adds: “If the British fail to do a deal, he could be looking at another six years in there. That’s a long time when you are 67.”

At the time of going to press, Ratcliffe was hoping to continue his hunger strike into this week. But he was worried about the effect on Gabriella, especially as he gets weaker. His daughter, who lived with her grandparents in Tehran after Nazanin was arrested and only returned to the UK in 2019, has been down to his ad-hoc campsite to carve pumpkins and paint pebbles with her classmates. But the situation will get tougher.

With diplomatic efforts now seemingly focused on creating a “grand bargain” for the British, Americans and Europeans who are being held unjustly in Iran, Ratcliffe feels that Nazanin has become an asset to be leveraged by the UK.

“There is a risk that by linking that simple transaction to a wider JCPOA agenda that she’s become an asset that’s leveraged by the UK as well. And that’s a challenge we’d put to the government: we think you’re playing chess with Nazanin’s life,” he said. “International diplomacy is rough but it’s tough when you’re the people being moved around the chessboard.”