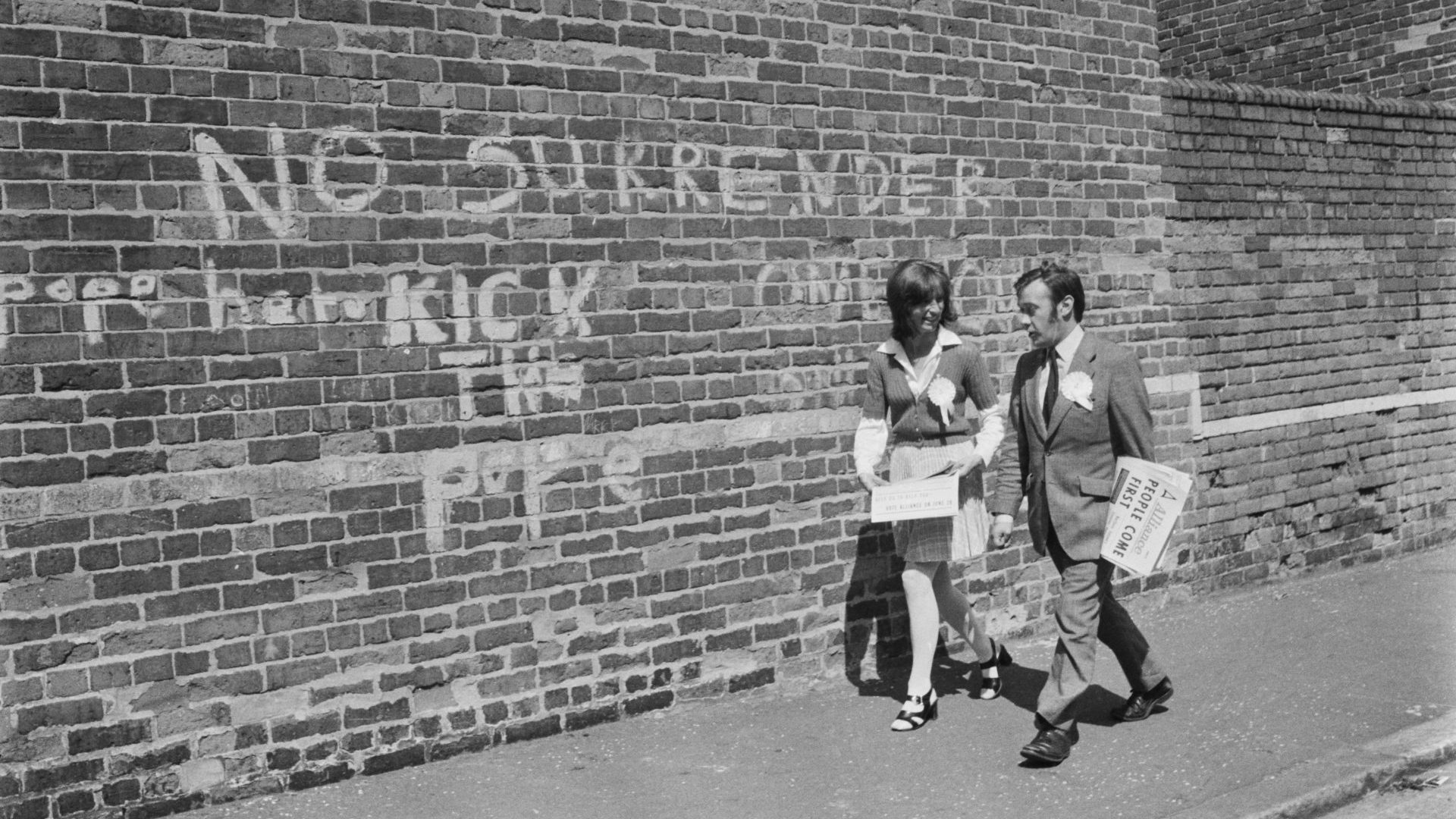

The first thing Patricia Burns remembers about the morning of July 14 1972 is the crowd of people that had gathered outside her Belfast home. Even if her six-and-a-half-year-old self hadn’t really known what to make of all the commotion, she recalls: “I knew something wasn’t right.” Soon, however, she was given an explanation: “They told me my father had been shot dead,” she says, “by the army.”

The night before, Thomas Burns had become one of more than 3,500 people killed during Northern Ireland’s decades-long agony known as the Troubles. What followed that devastating statement, made to her on the morning after her father was shot, were years of trauma and hardship.

“My mother could never speak about it,” Patricia tells me. “Suddenly, she had to look after four of us kids, from ages three to 11, all on her own. My brother went off the rails and ended up in a Christian brothers’ home, where there was all sorts of abuse, and we had no support, no counselling – nothing.”

Worrying away ever since then has been the dark uncertainty surrounding the exact circumstances of Thomas’s death that night, 50 years ago. Back then, he had been branded a terrorist by security forces and some local media. The official explanation for his death was that he had been shot down by soldiers defending themselves against a gunman. “I’ve spent my life trying to clear my daddy’s name,” Patricia says.

When the Troubles ended in the 1998 Good Friday Agreement, her chance came. Access to information about her father’s shooting and other cases opened up and, through her solicitor, she was able to see records from the official inquest into her father’s death, held in 1973. She was stunned.

“It was a complete mix-up of contradictory evidence,” Patricia says. “They kept saying my daddy had been shot by the soldiers, as he was a gunman, but the forensic swabs taken at the time showed that he hadn’t been carrying a gun.”

Years of further requests and appeals then followed. In a review of the case in 2013 by the now-disbanded Historical Enquiries Team (HET), one of the soldiers who had been present on the night her father was killed refuted the official record.

Finally, leave to apply for a judicial review was granted in March this year. The possibility of a full inquest is therefore finally – and tantalisingly – within reach. But if a new government bill currently before parliament becomes law, that possibility might be whisked away for ever.

The Northern Ireland Troubles (Legacy and Reconciliation) bill, which gets its second reading in the Lords on November 23, would see all current avenues for legal redress closed. Instead, they would be replaced by a government-appointed commission with the power to grant lifetime amnesties to those accused of involvement in Troubles-era crimes.

“If this bill becomes law,” Patricia told The New European, “only inquests that are already proceeding will continue, while any new ones won’t be able to start.” That would mean years of effort coming suddenly to a devastating halt.

Unsurprisingly, the bill has been almost universally condemned by victims and survivors’ groups on both sides of the Irish Sea.

“It’s obscene,” says Julie Hambleton, from the Justice4the21 campaign.

Her sister, Maxine, was among 21 civilians killed in the notorious Birmingham pub bombings of November 1974. Six men were arrested for the bombings, blamed on Irish nationalist paramilitaries of the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA), but the six were released in 1991 after being found wrongfully convicted. No one else has been charged with the crime.

Hambleton has since been campaigning for a proper inquest into the death of her sister and the 20 others – so far without success.

“The new bill is an insult to us and our loved ones,” she told The New European.

The bill is also opposed by all the parties in the Northern Ireland Assembly, whether Irish nationalist or British unionist, and all the Westminster opposition parties. It probably also breaks international law.

On September 23, the Council of Europe committee of ministers condemned the “minimal support for, and public confidence in the bill and its mechanisms in Northern Ireland from victims’ groups, civil society, the Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission and political representatives”.

Then on October 26, the joint UK parliamentary committee on human rights reported that the bill “risks failing to meet the minimum standards required to ensure effective investigations into Troubles-related cases concerning deaths and serious injury”.

The committee further urged the government to “reconsider”. The committee chair, Joanna Cherry, told the BBC she was very concerned that the bill was “not compatible with the right to life, which is guaranteed by article 2 of the European convention on human rights”.

Even Belfast-born actor Ciaran Hinds, of Harry Potter and Belfast fame, has issued a video for Amnesty UK appealing for the bill to be dropped.

Over the pond, both Republican and Democrat congressmen and women have objected to the bill, too. “Our united opposition to the legacy legislation will remain solid,” Republican congressman Mike Kelly told the Irish Times last month, when asked what impact Republican gains in the mid-term elections might have.

Yet the government still seems determined to push the bill through. “Why?” asks John Teggart, whose father, Danny, was among 11 civilians killed by the army in Ballymurphy, West Belfast, in August 1971. “Why should people who murdered civilians on British streets be given such treatment?”

Part of the answer lies in the long-running campaign by some Conservative backbenchers behind a 2019 general election manifesto pledge to “give veterans the protections they deserve”. This followed inquiries such as that into Bloody Sunday – the day in January 1972 when 14 civilians were killed by the army in Derry (then Londonderry), just six months after the Ballymurphy killings.

That inquiry took 12 years to complete and cost somewhere between £200m and £400m. In the end, four soldiers were found responsible for the killings, which Lord Saville, who headed the inquiry, described as “unjustified” and “unjustifiable”.

Only one of the troopers – known as “Soldier F” – now faces potential prosecution, after a September 22 decision by the Public Prosecution Service to resume proceedings against him following an earlier halt due to legal wrangling.

The case was polarising in Northern Ireland, while it also raised allegations of unfair treatment of servicemen elsewhere in the UK.

“Veterans are fed up with being demonised,” says Danny Kinahan, Veterans Commissioner for Northern Ireland. “Ninety percent of all those killed in the Troubles were killed by non-state forces, but if you read the national press, you might think it was always the army or police who were responsible.”

Boris Johnson himself promised to end “unfair” prosecutions of veterans in a campaign speech in 2019.

Tory MPs such as Jonny Mercer – reappointed by Rishi Sunak as Cabinet Office minister with responsibility for veterans after being fired by Liz Truss – have also argued strongly against putting now-aged former soldiers through the ordeal of investigation, particularly when the chances of a successful prosecution are close to zero due to the passage of time.

“The current system is broken,” adds Kinahan.

The bill therefore ends that system of inquests, civil and criminal prosecutions and other legal remedies and, instead, sets up a central, Independent Commission for Reconciliation and Information Recovery (ICRIR). Headed by a UK government-appointed official, this will hear voluntary testimony from those involved in Troubles-related cases. If the ICRIR believes these accounts “true to the best of [the testifier’s] knowledge and belief”, they will receive a lifetime amnesty in return.

Opponents of the bill argue, however, that the bill itself is what is really unfair. “This is all being done to meet the requests of a very small number of veterans,” says Ian Jeffers, head of the Northern Ireland Assembly’s Commission for Victims and Survivors in Northern Ireland (CVSNI).

Indeed, out of around 150,000 servicemen who served in Northern Ireland during the Troubles, only a handful of former soldiers are facing potential prosecution. “I know of only two,” says Julie Hambleton. “So why bring in a law that means murderers walk free, just for these?”

In addition, many victims and survivors’ groups blame the Ministry of Defence and other state institutions for the many years that inquiries and inquests can take.

“Everything has been a fight,” says Patricia Burns. “Obtaining papers, documents – they always put obstacles in your way and even when you get something, a lot is redacted.” Documents relating to the original, 1973 inquest into the death of her father, for example, were not released to the family’s solicitors for over two decades.

New procedures and technologies now available to investigators may also give current inquiries an edge over previous ones.

“At the height of the Troubles, inquests were done in hours or days, so you now have the opportunity to revisit these more calmly,” says Jeffers. In addition, ongoing investigations into Troubles-era crimes “show that through modern technology you can get to more information.”

The investigations Jeffers is referring to are those led by former Bedfordshire chief constable Jon Boutcher, including one into “Stakeknife”, the codename for a top PIRA leader who was also a British agent. This complex case is one of several controversial Troubles-related cases now being looked at. Back in 2020, the Lord Chief Justice launched a fully-funded five-year plan to look at 54 “legacy” cases involving 95 deaths.

“Much of this will stop if the bill becomes law,” says Patricia Coyle, from the Belfast solicitors Harte Coyle Collins, which is working on Patricia Burns’ case and has now lodged an appeal to the supreme court to halt the bill’s passage.

Stopping controversial investigations has also given rise to suspicions among victims and survivors’ groups – and others – that the bill is not concerned with helping them, but with preventing a light from being shone on some of the Troubles’ murkiest moments. Such inquiries have already revealed plenty of dark secrets.

Back in February, for example, an inquiry into a series of 1990s killings by pro-British loyalist gunmen held by the police ombudsman for Northern Ireland, Marie Anderson, found evidence of “collusive behaviour” between the gunmen and the Northern Ireland police of the time, the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC).

“You want to know who ordered some of the incidents back then, too,” says Jeffers. “Are we right in closing down that possibility for victims and survivors?”

The impact of the bill may also go far beyond the courts. Indeed, “It puts Northern Ireland in a very dangerous position,” says Coyle.

As the European human rights commissioner, Dunja Mijatović, said on July 4, the “virtually unanimous, cross-community rejection of the proposals also casts doubt over their potential to contribute to reconciliation in Northern Ireland”.

That process of reconciliation is a multifaceted one, but victims and survivors’ groups seem unanimous that this new bill, descending on them from Westminster, will do little to advance peace, let alone truth and justice.

After meeting Jeffers and the CVSNI, the secretary of state for Northern Ireland, Chris Heaton-Harris, said on October 10 that “the government remains willing to improve the legislation”, leading some to hope that the recent chaos in government might have given some space for a re-think.

Meanwhile, says Patricia Burns, “I can’t move on until we’ve cleared my daddy’s name.”

Ironically for a bill declaring its aim to be the ending of “vexatious” cases concerning veterans, Patricia’s father, Thomas Burns, had served in the Royal Navy for nine and a half years. He was also a veteran.

“No one wants this bill, on either side of the divide,” Patricia says. “For the first time in years, we’re at least all agreed on one thing.”