So, farewell then Vivienne Westwood, the dame of détournement. A disciple, sexual and business partner of pop impresario Malcolm McLaren, Westwood specialised in hijacking – or détourning – established styles and modes, so as to render them – at least superficially – radical. She took trousers – garments that by the 1970s had come to embody gender-neutral freedoms – and transformed them into items of fetish wear: strapping the legs together so the wearer was encumbered rather than liberated. She took T-shirts, those manifolds of the burgeoning classless, and ripped them, slashed them, and covered them with provocative slogans.

Then, in the 1980s, as punk rock was swamped by a new wave, she détourned the thriving British street fashion scene, of which she was the acknowledged avatar, by bootstrapping (an apposite locution) it into the realms of haute couture; becoming the first British designer to show in Paris for decades – and in the process spawning a gaggle of imitators, who waddled on after her, fastening corsets and brassieres over dresses, thereby reversing the inner and outerwear, just as she had inverted low and high.

There’s no doubt that she knew how to make clothes in every sense – but the idea that she represented a spirit of rebelliousness is frankly ridiculous: you are what you eat, and Westwood gobbled up till receipts from her numerous

brands. At her death she was reported as being worth in the region of £200m. At one time noted for her relatively humble and contemporary lifestyle, she died in one of the finest early-18th-century houses in south London. And then there was the “activism”: the Green Party’s principal donor, and a long-time supporter of fellow egomaniac Julian Assange, Westwood didn’t mind trashing her own money-maker, even as she shook it, urging people to buy fewer clothes, as this world-girdling industry is, of course, a major polluter.

As for the British establishment, Westwood went from lampooning the Queen to curtseying before her and accepting a title. That she twirled outside the gates of Buck House after the ceremony, thereby revealing she was naked beneath her sober skirt, was hardly likely to have the hierarchy quaking in its boots – after all, they share her avowed exhibitionism.

And then there was the occasion in 2016 when Westwood, together with her son by McLaren – Joe Corré, the lingerie magnate – took to the Thames, in emulation of the Sex Pistols’ notorious anti-Silver-Jubilee jaunt, and then burned what was allegedly a £6m collection of punk memorabilia.

This was perhaps the most egregious example of how Westwood had herself been détourned: it’s conceivably a radical gesture to expose the purely transactional nature of money when you don’t have very much of it – but when you have millions it’s both meaningless and deeply offensive to those who haven’t got any. The revolution will not be televised – and the acte gratuit cannot be scaled. She and her son were just as rich after the conflagration as before it – no one benefited, and moreover, no one really cared.

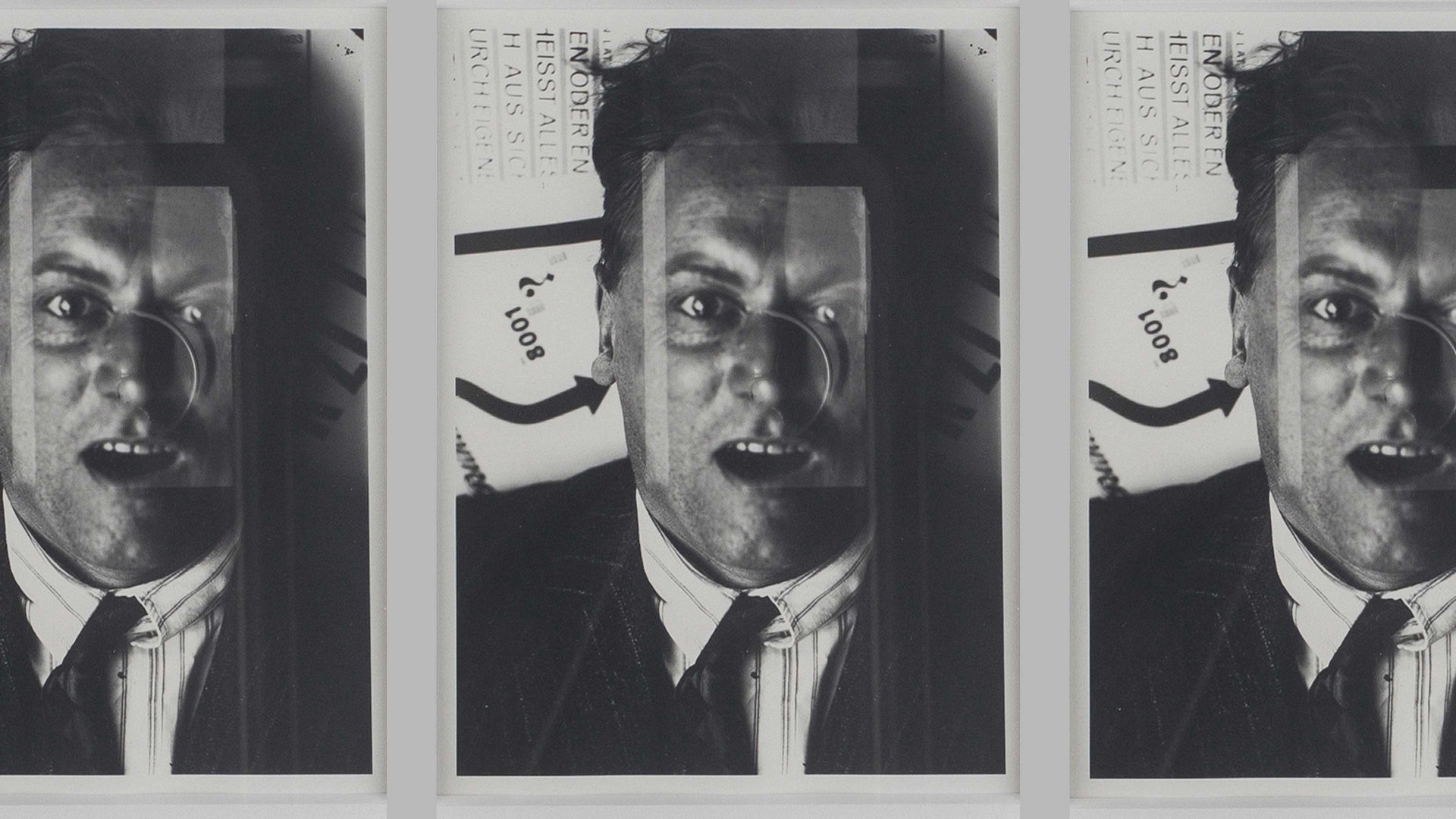

But then that was the fate Guy Debord, the ideologue of the Situationists – the Marxist art-revolutionary groupuscule he founded in 1950s Paris – had always envisaged for his ideas: for Debord détournement meant taking the techniques of consumer capitalism and using them to attack its spectacular forms. It was McLaren who cynically inverted this method by using the Sex Pistols’ anarchic rants to make hard cash. Westwood simply continued in the same lucrative vein. Punk was about doing it yourself – Westwood was about doing it to you… for a price.

As for the tired trope that she was a great English eccentric – she wasn’t: she was a great English hypocrite, and moreover, one who spouted nonsense about environmentalism and socialistic levelling the way a whale exhales: in great, foamy gouts of insubstantiality. Debord foresaw a world in which “A financier can be a singer, a lawyer a police spy, a baker can parade his literary tastes, an actor can be president, a chef can philosophise on the movements of baking as if they were landmarks in universal history.”

Westwood’s vapid, vatic statements made her a prime example of this development. By contrast, Debord viewed himself as being one of the last well-known individuals to have possessed “non-spectacular celebrity”, and when he realised the extent to which his ideas had been détourned by the ignorant army of which the likes of McLaren and Westwood formed the vanguard, he killed himself.

Requiescat in pace – and happy New Year everyone.