A teacher in a tough inner-city school hears one of his pupils fling a racial epithet at a classmate. Instantly, he calls the whole class to order and lectures them about the use of such terms: how they foster a climate of bigotry, exclusion and internecine conflict, and how they are completely unacceptable in his classroom. After this dressing down, the very pupil who was being racially abused goes to the school’s principal and reports the

teacher for having voiced these racial epithets in class. The principal calls the teacher to his office and gives him a severe dressing-down – the teacher, angered and bemused, replies that, yes, he did use them, but only to highlight their inadmissibility in discourse.

Sounds familiar, no? Highly contemporary, indeed – But no: for the teacher, a Mr Dadier, is played by Glenn Ford, and Miller, the pupil who has the n-word flung at him is portrayed by none other than the late – and deeply

lamented – Sidney Poitier, making his breakthrough film appearance. As for the film, it’s Blackboard Jungle (1955); which, if it’s remembered at all nowadays, is so for the use of Bill Haley & His Comets’ Rock Around the Clock, playing over the opening and closing credits.

This may’ve been the tocsin that awoke an entire generation to the rhythmic revolution of rock ‘n roll; but while the lyrics of Haley’s contemporaries, Danny and the Juniors, were prophetic: the music never has died – neither has the hate speech of the era: to this day the relationship between speech acts, physical ones, and institutional contexts remains deeply contentious. Glenn Ford’s Mr Dadier is exonerated once he explains the context to the principal, but 67 years later the consensus is that there can be no excuse whatsoever for certain words to be uttered. At least by certain people.

Each generation discovers this for themselves – and in the discovery imagines this to be their newfound, fissiparous land, and theirs alone. Yet something has shifted, nonetheless, in the arguments about sticks, stones, prejudicial epithets and broken bones.

Thirty years ago, I argued that while I had no wish to use the n-word, nonetheless I’d fight for the right to employ it in the appropriate context. But what was that context, and does it still seem appropriate to me now? I think so – but I’m conflicted: I deployed it in my novella, Cock (1992), to describe one of the characters’ sexual fantasies, and in so doing depicted the casual racism still current in the early 1990s.

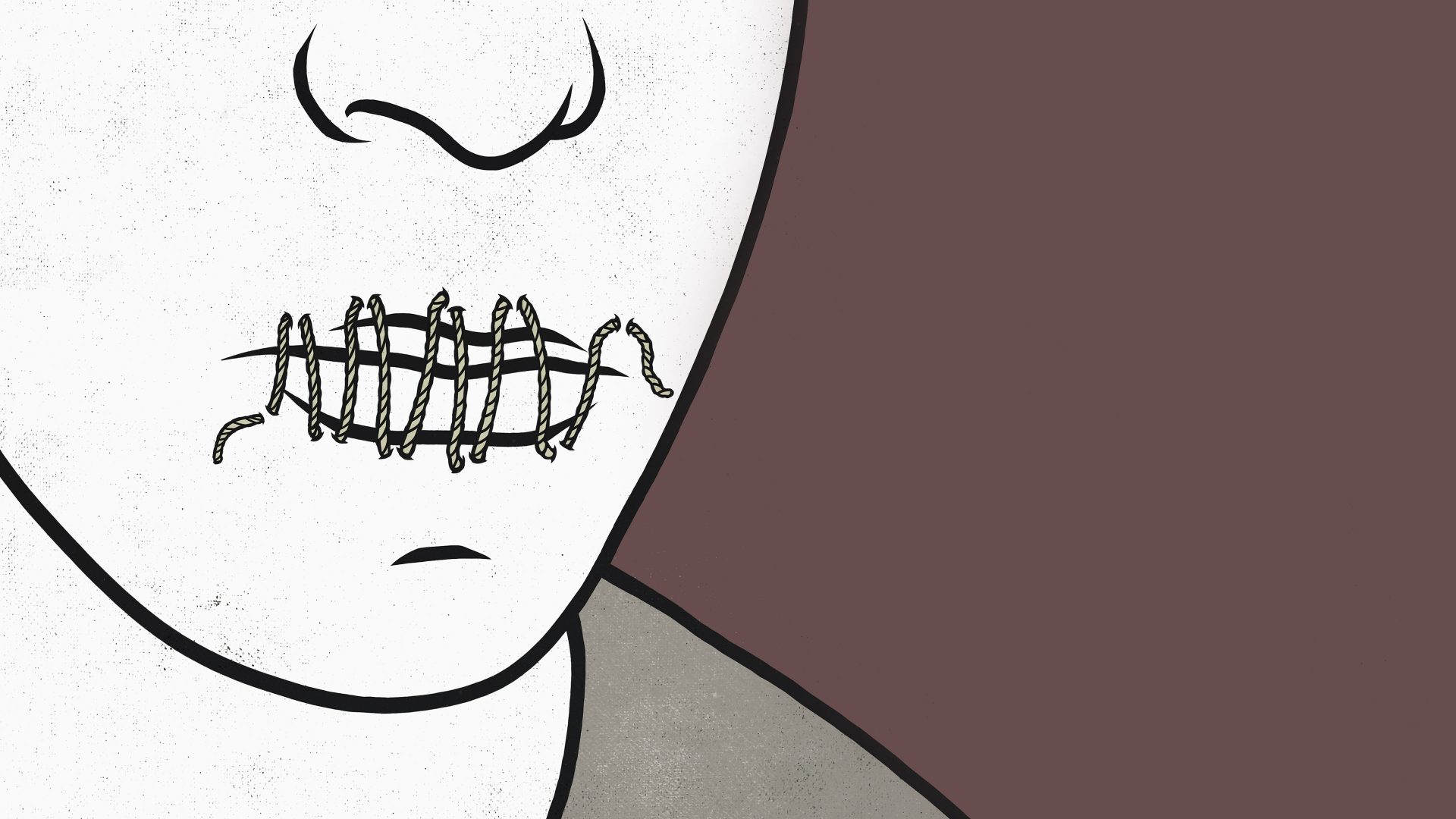

Obviously, written words are received in a different context to spoken ones – but both allow for discursive explanation. If I teach Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, I give a trigger warning to students about the ten instances of the

n-word in the text, but I also reserve the right – should we be discussing one of the relevant passages – to utter the word. In practice, I don’t think that has ever occurred (Huckleberry Finn might prove more problematic, since it’s bedizened with n-words), but the principle remains that to render any word unspeakable and un-writable, is to impose totalitarian double-think rather than advance the cause of racial justice.

I adverted above that there were certain people who could say the n-word (just as there are others who can deploy the y-one, or the f-one for that matter); the détournément of the n-word by African-American artists and performers is exemplary in this regard; but unfortunately, while the practice may induce a sense of solidarity in the face of oppression on the part of the

oppressed, it still – in my view – contributes to the entrenching of epithetic attitudes rather than their dissolution.

As to why, over the years, the commission of speech acts – no matter how they’re contextualised – has come to be seen as synonymous with physical ones and systemic oppression, surely this is a function of the ever-widening

gulf between the liberal rhetoric of inclusion and advancement, and the actual ability of societies such as our own to genuinely level-up.

As to my novella, Cock and its paired volume, Bull, the 30th anniversary of their publication gave me cause to reflect on another timeless semantic conflict: to whom can the terms ‘woman’ and ‘man’ be rightfully applied? In these narratives, I tried to consider just that – long before ‘TERF’ or ‘transgender’ were in common usage – with a depiction of spontaneous and uncalled for gender reassignment. Sensitive stuff, but the book has yet to be censured in the current and savage debate, because as I believe I’ve already

explained: while bigotry may be timeless, there’s a new kind of bigot born every minute.

Will Self’s novellas Cock & Bull are available in paperback and Kindle formats from Penguin Books