Every form of institution has its own culture – anyone who’s ever been to a school knows that. Indeed, even temporary human groups rapidly develop their own slang and customs – think of family holidays. Differentiating between us and them seems pretty much integral to naked apes – you might say othering is as important as belonging.

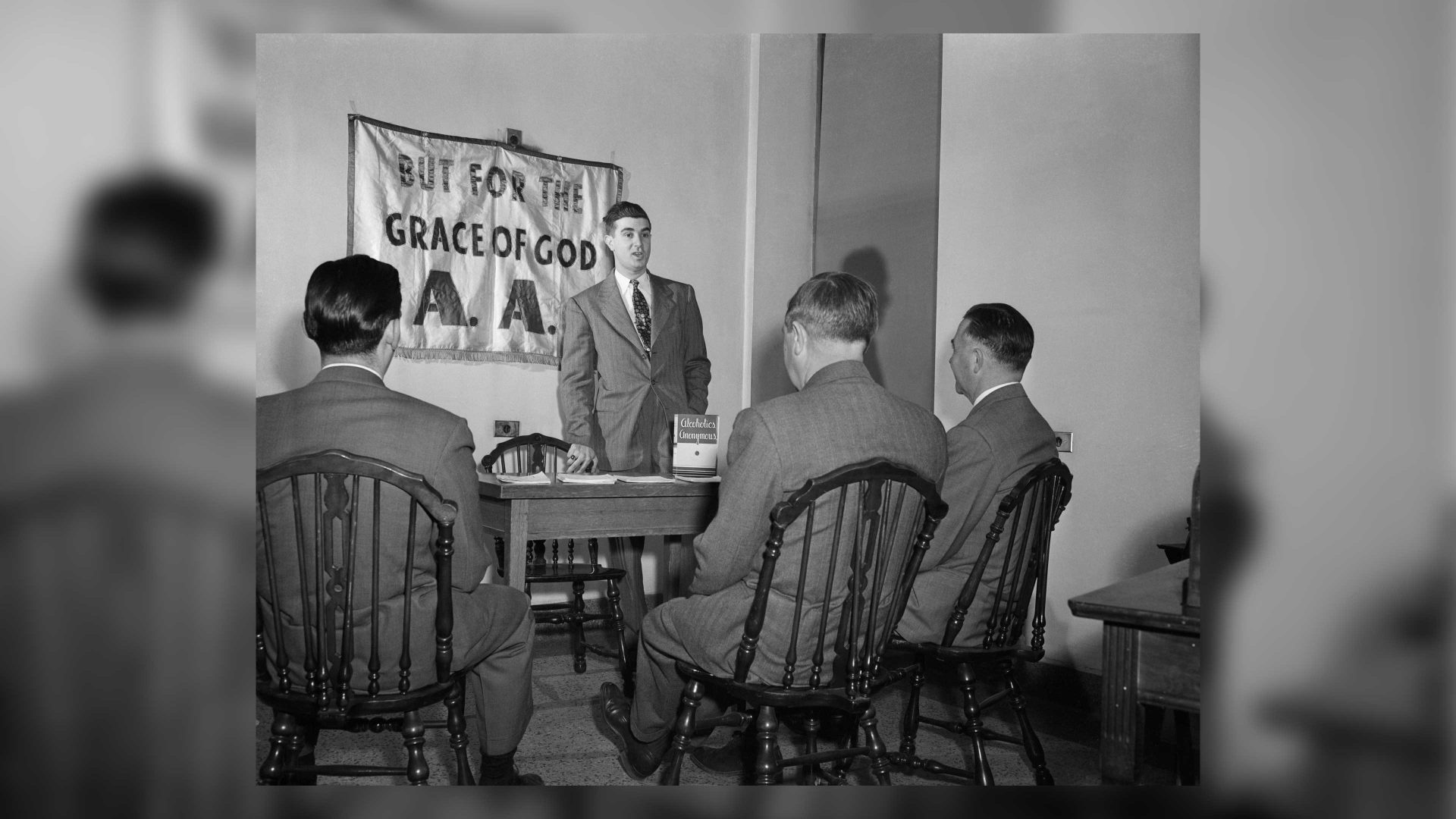

I remember being struck by how, even by the mid-1980s, when I – in the lugubrious coinage of the time – went “into rehab’’ – these facilities, designed to wean people off their pernicious addictions to drink and drugs, already had their own very distinctive culture. In part, this came pre-packaged from the Hazelden Center in Minnesota, a treatment unit for alcoholics that opened its doors in 1947, and which organised its programme around the 12 Steps of Alcoholics Anonymous.

Forty years later, the mixture of low-church revivalism and watered-down Freud that informed what had become known as “the Minnesota Method” was being further syncretised as rehab facilities opened their doors in economically depressed British seaside resorts. Yes, what a strange time the 1980s were: on the one hand, the wholesale destruction (or “transformation”, if you prefer) of the country’s industrial base, precipitating millions into poverty and initiating multi-generational mental health problems, including rampant heroin and alcohol abuse.

And on the other, trust circles, yoga sessions, group therapy, and A-line hugs, not class-A drugs. Even at the time, I found the juxtaposition of the leafy, somnolent Edwardian precincts of Weston-super-Mare (where this particular space cadet fell to earth) and the modish American psychobabble altogether bewildering. But one hotelier’s economic downturn is another private healthcare provider’s opportunity – and not just in Weston; fading resorts such as Boscombe, along the coast from Bournemouth, also became home to both primary care facilities and their attendant halfway houses.

Which acted as strange sorts of cultural vectors, bringing bohemian and middle-class professional types into these mouldering realms of no-longer-mod-cons, cracking Melamine and spalling pebbledash. I encountered the first person I ever met who was actually transitioning in Weston in 1985 – at the same time I was attending a local STD clinic, where the doctor who treated my genital warts told me that his solution to the Aids epidemic was to have all the homosexuals and drug addicts in the UK… castrated.

I digress – but the point is that the revitalisation of towns such as Margate and Hastings owe as much to the bed-and-breakfast as the Bilbao effect: just as some students stay on after their courses, and end up creating the culture of university towns, so recovered addicts and alcoholics stayed on in these resort ones, helping to create the sort of campervan countercultural vibe that made them attractive to big art galleries seeking new sites for development.

So: a virtuous sort of cycle really – from industrial proletarian, to opiate addict, to gallery-goer. Obviously, the children of the gallery-goers will be subject to the anomie of their pampered and so-called “creative” class – and no doubt many will become chemically dependent. Who knows what new worlds they’ll go on to conquer? A friend who’s come to roost in south-east Asia tells me that in Thailand, Cambodia – even Laos and Vietnam – all manner of rehab centres have sprung up, catering to a western clientele, many of whom will, no doubt, have indulged themselves in the region’s plentiful supplies of narcotics before checking in for six weeks of bell ringing on tatami mats while being roundly abused by Buddhist monks.

So, here too the process is dialectical: thesis being drug tourism, antithesis addiction, and the triumphant sublation of all being, the new synthesis of eastern devotional practices and western neoliberalism. It all seems a long way from William Butler, the pioneering detoxer, as described by John Aubrey in his Brief Lives, portraits of the celebrated personalities of his era, the revolutionary 1600s.

One of the cases that made Butler’s reputation concerned a prelate who, summoned to preach before the notoriously scholarly King James I, was so agitated the night before that he took an opium overdose. Butler asked the man’s wife if she would sacrifice one of the family cows to “fetch your husband to life again?” And when she assented “caused one presently to be killed and opened, and the parson to be taken out of his Bed and putt into the Cowes warm belly, which after some time brought him to life, or els he had infallibly dyed.”

Aubrey gives no indication of where the idea for the cow’s belly cure came from – and indeed, if you’re being picky, there’s no sense, either, that the patient was an addict of any kind, only that he overindulged on this particular occasion. And that – as any modern therapist will tell you, for a price – is nothing to be ashamed of.