There is a culture largely hidden from the one most of us affect to live in – a psychic realm beneath (or possibly above) it, wherein mysterious persons armed with occult machines enact torture and mind-control on the unwitting, so determining all manner of events, including political ones. If we encounter participants in this culture we tend to shy away from them, for what we choose to see as their delusions terrify us, while their eccentric behaviour and demeanour unsettles us.

They are, of course, those we diagnose as schizophrenic. The linkage between the nosology of this malady and the industrial-technical revolution that has made the modern world is itself a complex caduceus – one that makes hypocrites of Hippocrates’s followers.

The first recorded case history of what comes to be termed paranoid schizophrenia was undertaken in the Bethlem Hospital (the notorious Bedlam) in the early 1800s. The patient was one James Tilley Matthews, a tea merchant whose sea-green sympathies had led him to get mixed up in the French revolution, and end up imprisoned in the shadow of the guillotine for three years at the height of the Terror. But it wasn’t the so-called “national razor” that formed the content of Matthews’ delusions: after a flamboyant breakdown that saw him shouting accusations in the House of Commons at the then home secretary, Lord Liverpool, he began to stolidly maintain that a group he termed “the Air Loom gang” were at large in London, persecuting him and others with a bizarre machine.

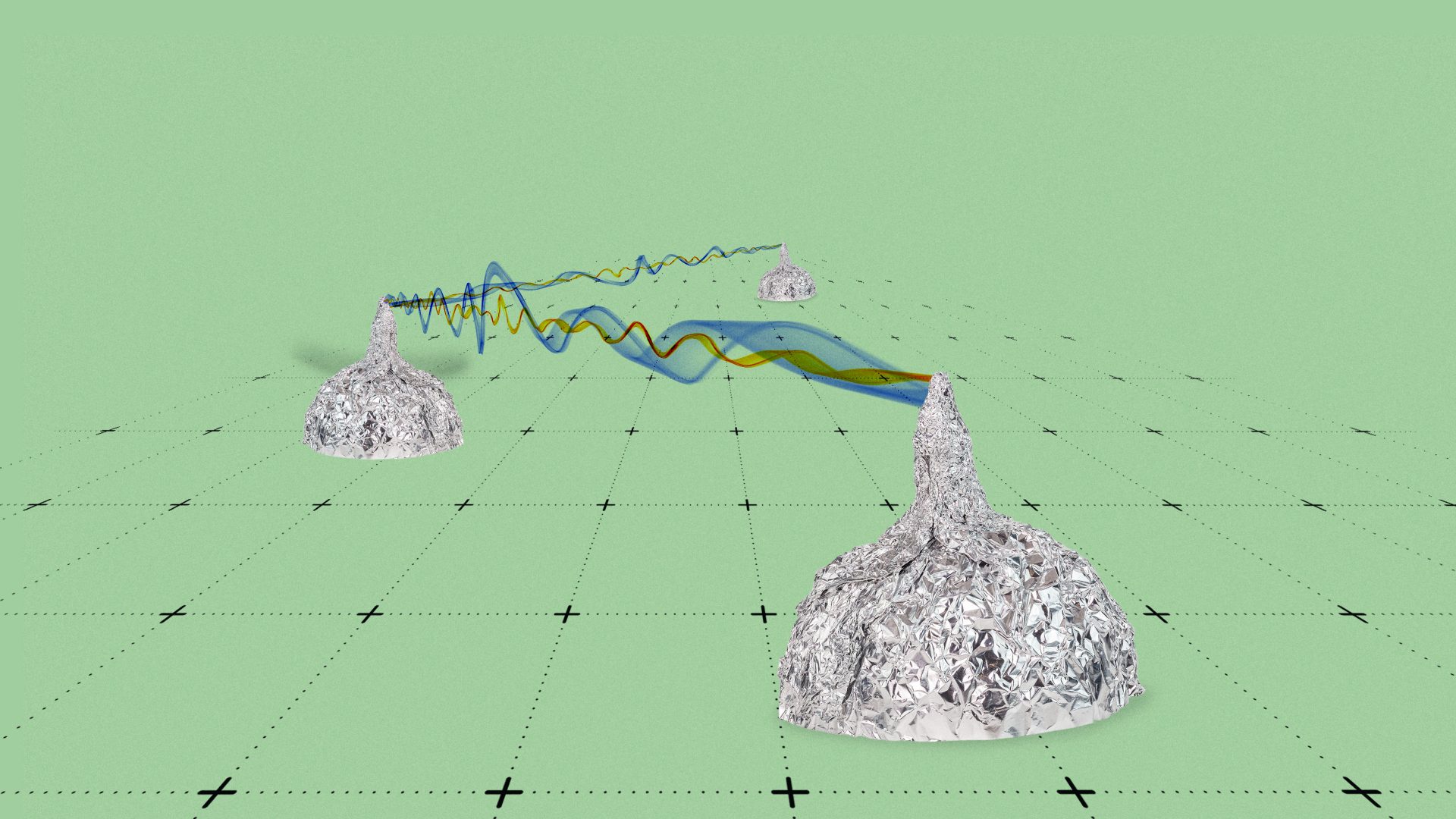

As conceived by Matthews – and exhaustively described by the physician John Haslam in his case history – the Air Loom weaved energy rather than cloth. The content of this delusion was furnished by an elision of the novel pneumatic chemistry of Humphry Davy, with the equally innovative Jacquard loom of 1804, which enabled the automatic weaving of complex patterned fabric using a system of punch cards. Alternately characterised as “a gaseous charge generator”, the Air Loom produced such grotesque effects in its victims as “lobster cracking”, whereby the blood’s circulation was interrupted by magnetic fluid; “stomach-skinning” and “apoplexy working with the meat grinder”, achieved by the introduction of fluids into the skull.

The correlation between emergent technologies and forms of psychosis then continues throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, as legions of poor victims are tormented successively via telegraph wires, telephone ones, radio and television waves – and, of course, in the contemporary era, by the enormous electronic grid of the internet, and its computer-woven web of voices and visions. But perhaps the saddest development – if it can be termed thus – in the schizophrenic culture of the past two decades has been the inception of a phenomenon termed “gang-stalking”.

If the image of the traditional psychotic is of one isolated by his or her torments, then the unifying characteristic of those afflicted by gang-stalking is that they, too, are a gang. Now able to find each other via the web, these online communities of schizoids exchange information on the latest incarnations of the Air Loom gang: sinister confreres, who, armed with psychotronic and directed-energy weapons, while deploying hypnotic suggestion via remotely accessed electronic devices, seek to manipulate persons and events.

It’s easy to see that the collective nature of the gang-stalking delusion must make it much harder to counter. In the past, if you confronted a psychotic with reality their usual recourse was to accuse you of belonging to whichever Air Loom gang was threatening them – but now they’ve instant access to a supportive online community, disabusing of this notion is next to impossible. It’s a bit like trying to convince a hard-line Brexiter, who receives all their news via the right-wing tabloid press, associated media and online forums of the like-minded, that leaving the EU has been an unmitigated disaster for the British economy.

Or, to be even-handed: a bit like convincing a TNE reader who also favours other media which reinforce their views that, withal the bumps in the road, the way is now clear to a more prosperous, free and democratic society. Indeed, the more you trouble to consider it, the more it seems inescapable: the convergence is not simply between psychopathology and technology, but between human consciousness conceived of collectively, and a virtual realm wherein mysterious persons armed with occult machines enact torture and mind-control on the unwitting, so determining all manner of events, including political ones.

It used to be that you could identify psychotics by their propensity for walking along the street talking out loud to the voices they could hear in their inner ear – now everyone does this. It used to be that only crazy people entertained the notion that machine intelligences were about to destroy the human world – now almost everyone does. Never before has the cliche that it’s a mad, mad world been… truer.