It was meant to be a celebration. In October 1989, Michael Eisner, the chairman of Disney, took to the steps of the Paris stock exchange flanked

by people dressed as Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck and Pluto. He was there

to announce the offer price of a share flotation in the company’s new European theme park, due to open three years later. But instead of being

welcomed with open arms, he was pelted with eggs and tomato ketchup

thrown by a 100-strong group of demonstrators chanting “Mickey go

home”. It was a portent of what was to come for EuroDisney.

As they walk down Main Street and take in the new shows choreographed

specially for Disneyland Paris’s 30th anniversary, most visitors would be forgiven for thinking that the park has grown from strength to strength since

it was opened in 1992. Sleeping Beauty Castle, the park’s iconic centrepiece, reopened last December after a 12-month renovation undertaken by the firm tasked with restoring the spire of Notre Dame Cathedral. Thanks to a €2bn (£1.68bn) investment, visitors will soon be able to channel their inner Tony Stark at the Avengers Campus, which will join the recently opened new “lands” based on Frozen and Star Wars. Yet the celebrations belie a troubled history and consistently lacklustre financial performance for the Magic Kingdom.

Disney’s first theme park, Disneyland, opened in Anaheim, California in 1955 and was followed 16 years later by Walt Disney World in Orlando, Florida. Then, in April 1983, came the first overseas park, Tokyo Disneyland. It was a huge success, welcoming 10 million visitors before its first birthday. Attendance continued to grow, but Disney didn’t reap the full financial rewards, having signed a licensing deal with the park’s Japanese owners, Oriental Land, which gave them only a percentage of revenue. This prompted them to open an overseas park of their own.

Western Europe was the natural choice. Disney films were historically

more successful there than in the United States. The Topolino comics featuring the so-called Sensational Six (Mickey Mouse and his friends Minnie, Donald and Daisy Duck, Goofy and Pluto) were among the most popular in Italy. In France, Le Journal de Mickey sold more than 200,000 copies each week.

Disney executives considered several potential locations. Neither Italy nor Britain could provide a tract of land large enough to accommodate their plans, while other countries were ruled out due to their inclement weather or because they were not significant tourist hubs. Two frontrunners emerged and became locked in a bidding war: a site on Spain’s Mediterranean coast near Barcelona and a 4,500-acre site at Marne-la-Vallée, an agricultural area some 16 miles east of Paris.

The Spanish government pledged financial incentives of around 80 billion pesetas (approximately £2.7bn in today’s money). Although their proposed site had the better climate, similar to California and Florida, the Tokyo park had shown this was not essential and ultimately in 1986 Disney chose France to host EuroDisney, as the park was originally called.

The French site had much to offer, not least its relatively central location. Paris welcomed 29 million tourists a year. Seventeen million people lived

within a two-hour drive, 109 million within a six-hour drive, and 310 million could reach the site in just two hours by plane. The EuroTunnel, set to open in 1994, would make access from England even easier. There were also

financial incentives. The French government made 4,700 acres of farmland available to Disney at below market price, provided the company with a $960m low-interest loan (about £2.3bn today) and helped to recruit private investors. They also agreed to extend the Paris Métro and build a station for the new TGV high-speed train at the park’s gates.

The success of the original Disneyland was based in part on a mix of idealised Americana fused with a pastiche of European culture and folklore. Its focal point, at the end of Main Street, USA, was Sleeping Beauty Castle, inspired by the 19th-century Neuschwanstein Castle built by King Ludwig ll of Bavaria. EuroDisney, situated as it was at the heart of the very culture Disneyland imitated, would require a careful and complex repackaging of that pastiche. After all, why travel to Paris to see the imitation, when the real thing (or any number of other castles dotted throughout Europe) was right on your doorstep?

Thus, Disney went out of its way to give the park a more European flavour. Walt Disney had drawn on the works of 17th-century French author Charles

Perrault for his early films Cinderella and Sleeping Beauty and attractions

based on these were marketed as a “homecoming” of European fairy tales. Tomorrowland, an area found at the three other parks that focused on the future and outer space, became the retro-future Discoveryland, inspired by the works of Jules Verne and other European visionaries such as Leonardo da Vinci and HG Wells. Eisner, Disney’s chief executive, called the result “European folklore with a Kansas twist”. It was a twist that left many in France unimpressed.

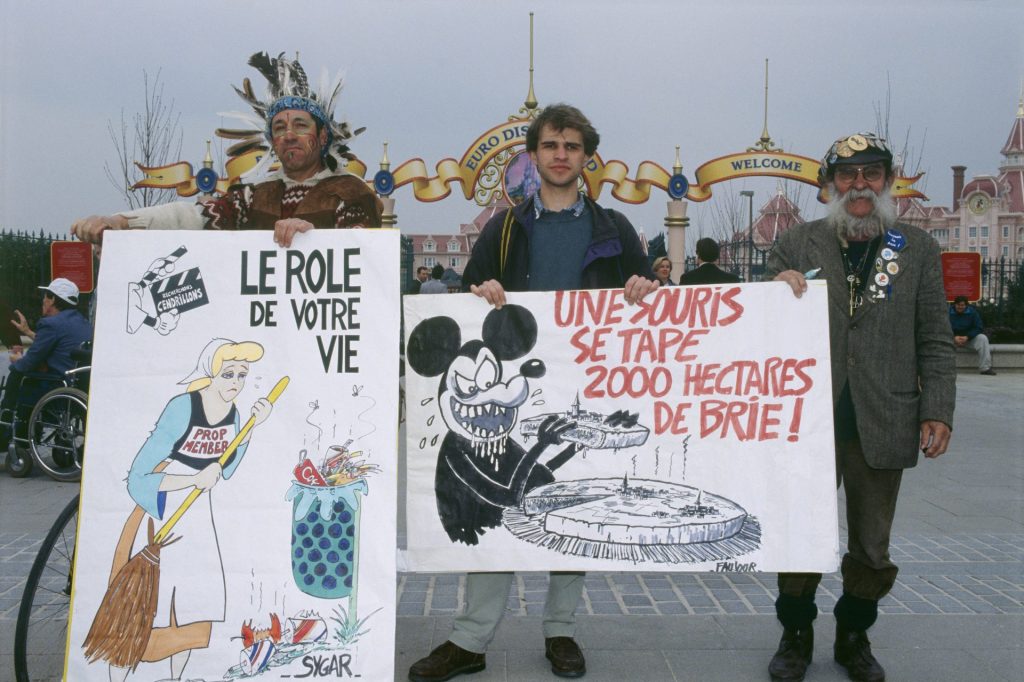

The inception and construction of EuroDisney took place during the Uruguay Round of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) negotiations. An update to the original 1947 agreement, the talks lasted seven years between 1986 and 1993 and were aimed at further reducing, or eliminating, international trade barriers. This sparked a debate in France about the homogenising impact of American cultural imports. The country insisted that cinema and television be exempt from the agreement, rallying other countries to its cause under the banner of l’exception Culturelle.

The government of François Mitterrand created a commission to protect the French language from the encroachment of franglais and imposed quotas on the foreign imports allowed on radio and television. Disney, along with McDonald’s and the TV show Dallas, became a derisory byword for low-quality, homogenised products in France.

These concerns intensified when it was announced EuroDisney was coming to the country. The magazine Le Nouvel Observateur greeted the news with a front cover adorned with an image of Mickey Mouse towering over the Eiffel Tower, Godzilla-like. “American Cultural Invasion: Is This Mouse Dangerous?” asked the headline. The most famous denunciation came from the theatre director Ariane Mnouchkine who warned that EuroDisney would be akin to a “cultural Chernobyl”. The journalist Jean Cau picked up the phrase, arguing that the park would “contaminate millions of children (and

their parents), castrate their imaginations, paw their dreams with greenish hands. Green, like the colour of the dollar.”

However, for Dr Sabrina Mittermeier, an expert on Disney theme parks, this was unrepresentative of popular feeling towards the park. “A lot of the intelligentsia was saying it was for ‘obese Americans’ – the French were too sophisticated for such a thing. That was all over the newspapers, but it was

a fringe opinion. It was never the case that the French were too sophisticated. No, they’re not! Neither are the English, neither are the Germans, people enjoy that type of stuff.”

In the face of such media criticism, Disney launched an aggressive marketing campaign, and the opening day celebrations were broadcast live

across the continent. However, the day itself was beset by problems. Two

small bombs intended to disable the power supply exploded the night before, although they were unsuccessful. French farmers, angry at the low levels of compensation they had received for their land, blocked roads to the park. Rail staff went on strike in protest at “imperialist colonisation”. More significantly, visitors simply stayed away. EuroDisney had a capacity of 50,000 (although daily entry figures could be higher as visitors would be admitted after others left) but on the opening day, just 25,000 turned up. Pictures of the half-empty car parks gave a desultory impression.

Behind the scenes, relations between Disney and many of its 14,000 new employees – referred to as cast members – were strained. As at its other parks, a strict dress code was imposed. Facial hair and nail polish was banned, and strict limits were placed on hair length, heel height and

earring size. Staff were forbidden from smoking, eating and drinking publicly. This was at odds with French cultural norms and workplace practice. Unions were angered, one labelling them a violation of “human dignity” while the restrictions were ridiculed in the press, which labelled it the “Mauschwitz scandal”.

Employees mounted organised campaigns. Female workers won the right to wear red lipstick and black tights, citing the fact that Minnie Mouse was allowed to. Disney eventually backed down, making the dress code voluntary, but employee protests have been a regular feature. In 2009, protesting workers blocked the route of the daily Disney parade, leading to its cancellation. Last year, hotel cleaning staff went on strike, leaving many guests without rooms.

Disney was also forced to make other cultural concessions. One of the biggest complaints from visitors was the park’s ban on alcohol. Although

this was, again, consistent with the policies in America and Tokyo, it was a

departure from traditional continental dining habits where people would

have a drink with their meals.

It was also considered a snub to the French wine industry, not least because the Champagne vineyards were little more than an hour’s drive away. The ban was soon lifted.

Despite this acquiescence, the global recession hit the park hard. It failed to

meet its first-year target of 11 million visitors; its hotels were rarely more

than half full, well below the anticipated 68% occupancy levels. EuroDisney recorded a $300m loss in its first 12 months. In its second it lost an eye-watering $920m. With the park on the verge of bankruptcy, Eisner said of its future: “Everything is possible… including closure.”

“The fact that he would loudly entertain the possibility showed the situation was very bad,” says Mittermeier. “However, I can’t see him having actually closed it. Disney would have never come back from that; it would have damaged their reputation beyond belief.” If Eisner was bluffing, it worked. The park’s creditors blinked and renegotiated their loan terms. The park survived.

It was at this time that EuroDisney became Disneyland Paris. While for Americans the word “Euro” was glamorous, for Europeans it was associated with business, currency, and commerce. Conversely, “Paris” conjured up the sense of romance and magic Disney wanted to capture.

Finally in 1995, the park returned its first, small profit. It was only a temporary respite. Although it is Europe’s most visited tourist attraction, the resort has only rarely done so since. Disneyland Paris welcomed 15.6 million visitors in 2012 as it celebrated its 20th anniversary, yet it was still weighed down with a debt of €1.9bn. In 2014, with visitor numbers falling and annual losses mounting, the park was forced to ask its parent company for an emergency loan of €1bn (£785m).

Three years later, as the resort turned 25, Disney in effect bought out its operating company, Euro Disney Associés, gaining full control of the park’s future direction. In 2019 the park recorded its first annual profit in 11 years. Then Covid hit.

Forced to close twice in 2020, the second time from October until July the following year, Disneyland Paris suffered more than the other parks. When it did open briefly, travel restrictions and social distancing measures limited the number of guests.

It’s hard to yet quantify the financial impact this has had on Disneyland Paris, but the company’s theme park arm (which now also includes parks in

Hong Kong and Shanghai) has lost billions due to the pandemic. The impact of the closure for business in the Eastern Paris Basin in which it sits runs into the tens of millions.

It’s this economic impact that is arguably the park’s biggest legacy. With 17,000 “cast members”, Disneyland Paris is the largest single-site employer in France. It has boosted the French economy by approximately €70bn (around £58bn) since it opened. The Val d’Europe region, once little more than beet and potato fields, is now a thriving residential area that is also home to a major shopping centre and international business park.

This has helped to quell the once virulent cultural concerns, and in the 30 years since it opened, Disneyland Paris has become as recognisably French as the Eiffel Tower or the Louvre. “Most people don’t think about it,” says Mittermeier. “There will be people who don’t like it, but I don’t think anyone’s actively upset about it, because what’s the point? It’s just there. It’s part of the country.”

Roger Domeneghetti is a senior lecturer in journalism at Northumbria University and writes for, among others, The Times Literary Supplement, Wisden and The Blizzard