There is no shortage of babies in the history of art. Most, admittedly, are versions of Jesus Christ, in a manger, on his mother’s lap, feeding at her breast. But rarely do these resemble the infants we know or nurture ourselves, being inclined to myriad incongruities – too tall, too flabby, too elderly.

The very young, as depicted by some of the female artists in an exhibition at

the Royal Academy of Arts in London, are closer to home, with their dumpy

arms and stumpy legs. Paula Modersohn-Becker captures one commonplace pose with rare observation. The infant in her Baby, Breastfeeding (c1904) is, unusually, properly latched on. It takes all the effort of another little girl to bundle a small cat in the crook of her elbow, while her Boy in the Snow looks all but immobilised by his room-to-grow boots.

Käthe Kollwitz drew throughout her long career on the losses in her own life and on awareness of her physician husband’s suffering patients. Figures conjoined by agony or ecstasy in the many etchings she produced are alarmingly ambiguous: are they cuddling, or clinging to a corpse? Unflinching and Goya-esque, she confronts the hideous shadow of death that haunts every parent.

Both Becker and Kollwitz were mothers, but both had tragic stories. Paula Becker was born in 1876 in Dresden into a comfortable, liberal and culturally minded home that encouraged her to gain financial independence by training as a teacher alongside the art studies she favoured. Once qualified, in her early 20s she joined the avant-garde Worpswede artists’ colony north-east of Bremen, having been impressed by, in particular, the work and person of Otto Modersohn.

The two artists married in 1901, but the union stymied her professional ambitions. Through the poet Rainer Maria Rilke, she met the sculptor Auguste Rodin and worked for him in Paris, where she was influenced both

by the French post-impressionists and by the historic art from other cultures

that she observed at the Louvre.

Radically posing nude for her own paintings, she brought reality to the mother-and-child composition. But in her own life, motherhood was short.

Having split from and then returned to Modersohn, she bore a daughter,

Mathilde. Postpartum bed rest, then commonly and misguidedly advised, caused a pulmonary embolism, and Becker died a month later, aged 31. Despite the brevity of her life and career, she left more than 700 paintings and 1,500 works on paper, some of the most expressive of which are in Making Modernism, largely loaned by German collections.

Kollwitz, née Schmidt, nine years before Becker, outlived her by nearly four decades, but she bore terrible reverses throughout her long life. Born, like Becker, in Königsberg, now the Russian enclave Kaliningrad, unusually for the time she was encouraged by her progressive parents. Her artistic talent becoming clear, she trained in Berlin and Munich. Her confident and Rembrandt-like self-portrait of 1889, in her early 20s, is skilled and incisive – and is one of more than 100 self-portraits.

But she by no means confined herself to such pieces or family scenes. Her print cycle The Weavers’ Revolt, inspired by an uprising in Silesia in 1844, attracted the attention of important contemporaries and prompted both an

invitation to exhibit with the new breakaway Berlin Secession and a travel prize to Florence.

Like Becker, Kollwitz knew Rodin, his visceral, tormented figures clearly influencing her own. She wrote admiringly of “his creations so compelling, convincing and infectiously passionate”. She experimented with three-dimensional work herself; her Mourning Parents sculpture can be seen in the German War Cemetery near Vladslo in Belgium.

The location is significant and poignant. Within months of the outbreak of WWI, her son Peter, barely old enough to serve, was killed in action and buried there. Tormented by supporting his desire to enlist, Kollwitz became a committed pacifist, lending her talents to anti-war poster and print campaigns.

Such campaigns were to no avail, and Kollwitz was dealt a second cruel blow with the death on the Eastern Front in 1942 of her grandson, also named Peter after his dead uncle. By this time, the artist had also lost her husband of nearly 50 years, the passionate social reformer and doctor Karl Kollwitz.

Hans’s practice looked after the families of textile workers, and the couple had set up their first home in a working-class area of Berlin. Their first child, Hans, almost died of diphtheria picked up at the practice in his teens. The personal and societal losses and anxieties that Käthe Kollwitz bore make her the most profound artist in this exhibition.

Perhaps better known is Gabriele Münter. However, as has repeatedly been the fate of female artists, her fame has until now been primarily by association with a more famous man. In the case of Münter, it was German

expressionist Vasily Kandinsky who attracted the greater attention. Their relationship began when Münter, another young woman whose art flourished against a comfortable and educated background, enrolled in life

drawing and painting classes taught by Kandinsky, 11 years her senior, in

Munich. Kandinsky was already married, but the couple became secretly engaged nonetheless, and travelled extensively for several years, painting en plein air at locations as varied as the Swiss Alps, the French Riviera and Tunisia. But it was in the ancient Bavarian market town of Murnau, on the shores of the Staffelsee, that Münter found herself most inspired, saying, “Nowhere had I seen such an abundance of fine views in one place.”

In 1908 Münter held a solo exhibition in Cologne and spent the summer with Kandinsky and another artist couple, Marianne Werefkin and Alexei Jawlensky. The liberation of which she wrote manifested itself in a change to flatter brushwork in her painting style. Interior in Murnau (c1910), with its exaggerated perspective, allows receding floorboards to dwarf her bearded partner, their relationship humorously marked by her shoes and his at opposite ends of a brightly striped rug.

Artists were drawn to Murnau and to the gabled house in Kottmüllerallee that Münter bought and decorated exuberantly with Kandinsky. It became known as “the Russians’ house”, and can be visited to this day. Guests included the future founding members of Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) group, Franz Marc and August Macke, who emulated Kandinsky’s deconstructed compositions and radical use of colour, and the composer Arnold Schönberg, who was doing something similar with his 12-tone scale,

breaking away from tonality.

But while Kandinsky was edging away from figurative painting, Münter stuck pretty closely to domestic scenes, albeit with celebrity models including the artist Paul Klee, who sits squarely in front of Münter’s collection of folk art in a painting from 1913. A year later, the couple fled to Switzerland and went their separate ways, Kandinsky returning to Russia, Münter moving on to Sweden and Denmark, and turning, once the relationship ended, to portraiture for a living.

Arguably her greatest contribution to art, however, was in rescuing and hiding, in her Murnau basement, important works classed as degenerate by the Nazis. Her accomplice in this invaluable act of art housekeeping was her admirer and then partner, the art historian and philosopher Johannes Eichner. In donating the collection to the Lenbachhaus in Munich, they helped to make the gallery’s holding of Blue Rider art the greatest such collection in the world.

Also eclipsed by her more famous partner was Werefkin, the well-travelled daughter of Russian aristocrats. Postings for her father took her all over the Russian empire, and she was educated to a high level. When Tsar Alexander II gave her father an estate in modern-day Lithuania, he built his daughter an art studio there. Frustrated by a move to St Petersburg where art academies did not admit women, she studied privately for 10 years with the Russian realist Ilya Repin.

Repin introduced her to Jawlensky who, in the course of their 18-year relationship, did not encourage her talent. But he benefited from the pension she received on the death of her father. This helped to fund apartments in Munich, Werefkind’s influential salon, and friendship with Kandinsky and Münter.

Surviving the first world war in Switzerland, Werefkin moved to Ascona on Lake Maggiore, her home until her death in 1938. Here, by persuading other artists to donate their work, she co-founded the Museo Comunale d’Arte Moderna, where much of her own work can be seen.

After early domestic scenes, later paintings captured the resignation of small-town mountain folk. But perhaps her most striking image dates from 1909. Two nannies on a bench, with complexions as green as the painted door alongside, nurse two sickly-faced babes with rosebud mouths. It is

entitled Twins, but who are the siblings? The adults? The babies? Both? Certainly neither child was Werefkind’s. Jawlensky’s son, Andreas, was born to the couple’s housekeeper.

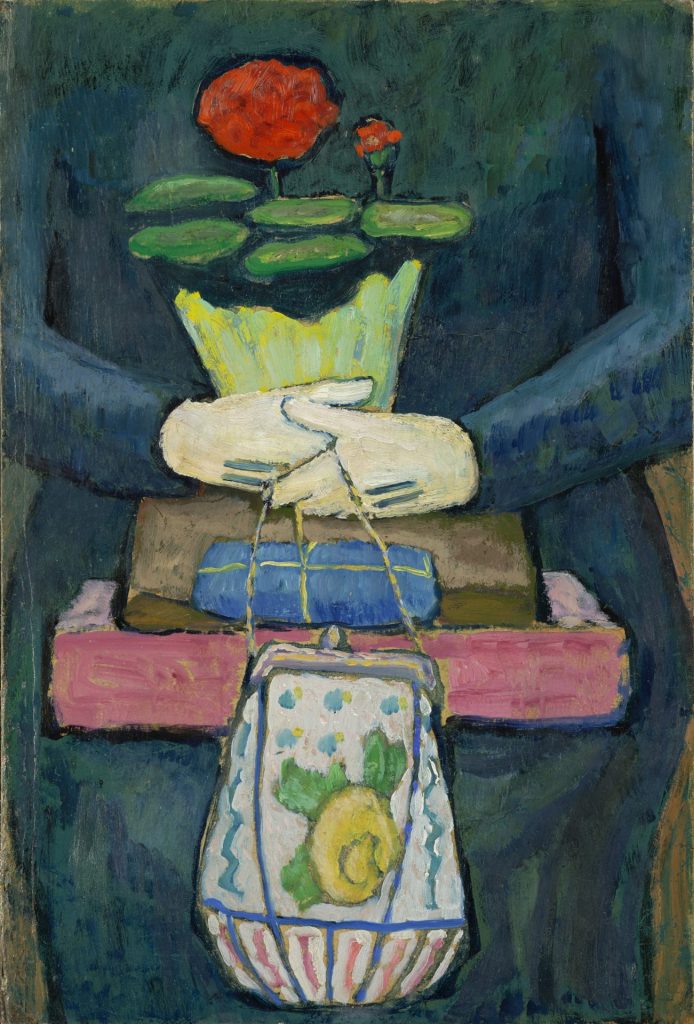

Whether short-lived, crippled by grief or the survivors of broken relationships with prominent men, these artists, for all their comfortable

starts in life, bring an unusual vision to the modest scene. Münter’s Still-life

on the Tram (After Shopping) from 1912 homes in on an almost ceremonial

stack of purchases balanced above a decoratively worked bag and topped off by a pot plant. It is a totem pole in honour of domestic life.

Making Modernism is at the Royal Academy of Arts, London until February

Claudia Pritchard writes about the visual arts, opera and classical music