Nobody’s even sure what to call it. In French, it’s Ascenseur pour l’échafaud, which translates as Lift to the Scaffold. That then translates into Elevator to the Gallows in America. But on its original US release, the film was called Frantic, to which title Roman Polanski paid homage in his 1988 Paris thriller, starring Harrison Ford and Emmanuelle Seigner.

But the film itself has probably been overshadowed by the enduring reputation of its soundtrack. Recorded by Miles Davis and a group of French musicians, it is still considered one of the coolest and most distinctive musical accompaniments in the history of cinema, and an important work in the development of jazz. The album has always kept the French title, prompting generations of jazz fans to mangle the pronunciation in attempts to sound sophisticated. In America, it was released as one side of a 1958 Miles Davis compilation LP under the much easier name Jazz Track.

“It’s the epitome of sophistication,” says Guy Barker, the award-winning trumpeter, band leader and film composer. “Miles Davis’s trumpet creates a whole atmosphere for the movie and it’s a mood he then carried on into making the most atmospheric album ever, Kind of Blue, just two years later. The combination of sound and image is just perfection, and people still hanker after it today.”

Barker has played trumpet on music-tinged films such as The Talented Mr Ripley, with its ’50s Italian vibe, and the Édith Piaf biopic La Vie en Rose, starring Marion Cotillard, in a performance that won her an Oscar. But he admits with a laugh that he’s still most often asked by directors if he could “sound a bit like Miles Davis”.

“And what they’re really referring to is Lift to the Scaffold,” he says. “Maybe even without knowing it, so iconic and significant is the music in that film. And, the thing is, you don’t shrug or complain as a trumpeter. You get your Harmon mute and do your very best to capture that sound, that mood. It has a distinctive loneliness that haunts the air.”

Davis pioneered the muted trumpet sound on his early ’50s records such as Cookin’ and Walkin’, with some tunes later gathered on the breakthrough Birth of the Cool album. That record, released in 1957, introduced a new, modern sound into the world of jazz, the frenetic pace of bebop replaced by a more introverted, restrained form. That came out just a few months before he laid down the music for Lift to the Scaffold.

Scaffold sits uniquely in the Davis discography because it’s an improvised piece inspired by the characters and actions of a film. The recording has become a legendary movie anecdote. The story goes that Miles went into a studio one night in Paris in December 1957 and improvised the music over images played for him by the director, Louis Malle. In essence, it’s a live score, which perhaps adds to the urgency of the uptempo pieces, such as the car chase on Sur L’Autoroute and Dîner au Motel, and the plangency of the unforgettable nocturnal wandering scenes such as Florence Sur Les Champs-Élysées.

There is, of course, a bit more to the myth. Davis wasn’t someone who’d take on a job lightly – he’d never just turn up and play, with no preparation. Malle had in fact shown the visiting American jazz star a cut of the film a few days earlier. Having got to Davis through the pair’s mutual friend, the poet Boris Vian (who a few years earlier had introduced Miles to Juliette Gréco, leading to a lifelong love affair), Malle had already played the film twice to Miles and the pair had discussed the scenes they felt needed some music.

Having absorbed the film, and despite not having his usual band of musicians with him, Davis then went away to write in his hotel room at La Louisiane on Rue de Seine in Saint-Germain-des-Prés. This was 18 months before the French Algerian pianist Martial Solal, who had previously worked with Django Reinhart, composed the jazz score for Jean-Luc Godard’s À bout de souffle. It was Miles who paved the way for France’s jazz and New Wave combination.

Co-opting a black American music idiom to accompany French film must have seemed exotic and intellectually daring at the time. The jazz sound was a reaction to what the new generation of filmmakers and critics viewed as the stuffy old “cinema de Papa”. But beneath that, the music lent the images an intense feeling of inner turmoil and alienation, which seemed to accord with French anxiety over post-war guilt and the brutal realities of colonialism in Indochina and Algeria.

For all the freedoms that Miles says he enjoyed while in Paris, there’s a certain irony in white directors using a slice of the black American experience to enrich their movies. As Jack Chambers wrote of this trend in his biography of Davis, Milestones: “The use of jazz-derived soundtracks became so predominant that jazz came to seem like the natural backdrop for high-speed chases, mass mayhem and cold-blooded murder.”

Were French producers exploiting a dangerous edge with jazz, profiting from these men banished from New York? In his New Yorker essay, Richard Brody says that “given jazz is essentially an African-American art form and the movies were all made by white producers, the association is all the more unpleasant and all the more unfortunately explicable,” although he’s quick to add that there’s “nothing violent or sinister about Davis’ music for Elevator to the Gallows”.

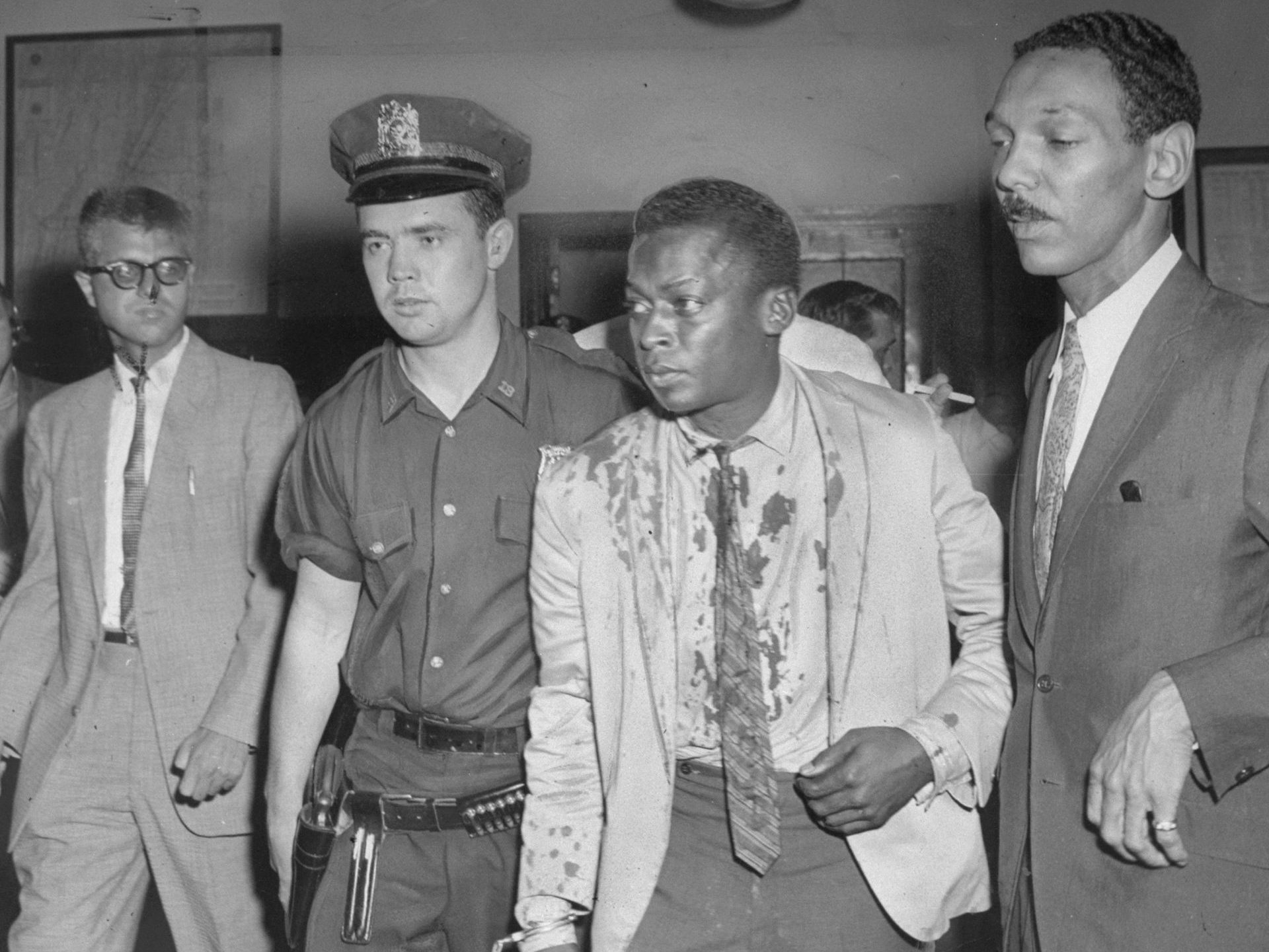

But the threat faced even by a high-profile artist such as Davis was deeply sinister and very real. One evening, while taking a cigarette break outside Birdland, the nightclub just north of West 52nd Street, a white policeman told him to move on. Davis famously responded by pointing to the marquee lights above the entrance and saying: “That’s my name up there, Miles Davis.” Photographs taken later that evening show Davis handcuffed and covered in blood.

It would not have been a great surprise if Miles had never returned to the US, especially as he found something special over those December nights in Paris. He picked three gifted French session players – Barney Wilen on sax, René Urtréger on piano and Pierre Michelot on bass – and gave them brief guidance on the changes he had in mind. The drummer Kenny Clarke was also around. Clarke had never returned to America, having visited Paris a few years before and found freedom and acceptance there. Malle later said: “What Miles did was remarkable. It transformed the film. I remember very well how it was without the music, but when we got to the final mix and added the music, it seemed like the film suddenly took off.

“It was not like a lot of film music, emphasising or trying to add to the emotion that is implicit in the images and the rest of the soundtrack. It was

a counterpoint, it was elegiac – and it was somewhat detached. But it also created a certain mood for the film. I remember the opening scene; the Miles Davis trumpet gave it a tone, which added tremendously to the first images – without Miles Davis’s score the film would not have had the critical and public response that it had.”

Malle was 25 years old and it was his first movie, although he had previously worked as co-director with Jacques Cousteau on the pioneering, Oscar-winning undersea documentary The Silent World. This was a different world entirely – having brought light to life beneath the waves, he now cast Paris into semi-darkness, producing a film noir that eschewed artificial light to better catch the modernity of the changing city, with its neon shop signs, car headlamps and shiny metal.

In that most famous sequence, Jeanne Moreau’s Florence wanders the Champs-Élysées gliding in an inky black sea, only the flashes of fenders, cafe fronts, clothes shops and glistening reflections to light her way. Much was made at the time of her being photographed without makeup.

Malle’s camera operator was Henri Decaë, a man credited with making the New Wave possible by liberating the camera from its fixed tripod. Here, he and the camera sat in an adapted child’s pram to get the travelling shot, techniques that just months later he would use again on François Truffaut’s The 400 Blows.

As the film theorist and scholar Ginette Vincendeau wrote later: “From her huge close-up at the opening of Lift to the Scaffold, Moreau was at the centre of a shift in the representation of female eroticism, from the body to the face. Her face connoted interiority, her full, slightly downturned lips gave her a proud, independent allure. Moreau brought to the cinema a new type of glamour, less overtly sexy than Bardot, more cerebral – she was known offscreen as a cultured woman, in tune with the new art cinema. With Moreau, the ‘new woman’ of the New Wave had arrived.”

The New Yorker critic Richard Brody, who wrote a book on Godard, believes the movie Lift to the Scaffold isn’t half as good as its soundtrack. In 2016, Brody wrote an essay when the film was remastered and re-released by Criterion, in which he suggested simply listening to Davis’s music rather than hearing it in the movie.

I disagree. There’s a brief minute or two of behind-the-scenes footage on that Criterion DVD, of Davis, dressed in striped tie and a blazer with an embroidered badge on the pocket, playing to the scene of Moreau walking the night. A curlicue of smoke wafts upwards, but you can’t see any cigarette so it appears that the trumpet itself is smoking.

At the sound desk, Malle is interviewed, explaining that what’s happening is all improvised and that nothing has been written down. “So it’s just as it comes to him?” asks the interviewer with surprise. “So it might be a different music tomorrow?” Yes, Malle says, explaining that it’s even different from one take to the next.

Jazz fans have noted how this session marks Davis’s move towards a more modal form of jazz, one based less on a set pattern of chords, and instead dependent on the music shifting between different scales. This was something Davis explored in his seminal albums Milestones, 1958, and Kind of Blue, 1959.

The mythology around the recording has grown over the years. According to the bassist, Michelot, the group had been playing together over the course of a short European tour. The intention was to film that tour with the young documentary maker Jean-Paul Rappeneau (later famous for directing the 1990 hit Cyrano, with Gérard Depardieu), but he couldn’t find the time as he was already assisting Malle on the edit for Ascenseur. It was Rappeneau who suggested Davis for the music.

“Jeanne Moreau was there in the studio,” recalled Michelot. “We all had a drink, Miles was very relaxed, I didn’t even know he had already seen the movie and had been thinking about the music for a while. We musicians had only the most succinct guidance from Miles. He’d say you play D minor and then you play C7, and we’d say, OK.”

For a film about crimes of passion and lovers on the run and how the mechanisms of modernity can entrap humans – literally, the leading man (Maurice Ronet) is trapped in a lift for the weekend, having gone back to tidy up the scene of his crime – this modern music feels as if it wreaths itself around the characters.

As Barker says, it puts the film on the edge. “It’s such a fragile trumpet sound, but it’s come to define what trumpet sounds like in the movies,” he tells me. Barker says he’s often asked to create jazz that can define the era or period of a film, but that Lift to the Scaffold stands out as something different. “For me,” he says, “the music makes it timeless and the characters seem to achieve a kind of freedom through the music, even though they are quite clearly trapped. It’s as if the music is their escape.”

Davis himself also found freedom in Paris. On his first visit there in 1949, he fell in love with Gréco. When Jean-Paul Sartre asked him why he wouldn’t marry her, Davis is reported to have told the philosopher: “I love her too much to make her unhappy.”

It’s not certain whether he was referring to the racism that would have haunted a black and white couple in America, or to his own self-knowledge of his relentless womanising. Although the love affair between Davis and Gréco is rumoured to have lasted all their lives, by the time of recording Ascenseur, Miles was having an affair with Moreau (maybe as a result of that night in the studio?), which is a bit complicated because by the time her next film with Malle, Les Amants, was released just eight months later in 1958, Moreau was having an affair with the director. Les Amants scandalised audiences, from the Catholic Italians who saw it at its Venice film festival premiere, to the bourgeoisie of France who felt it threatened and satirised them, to even being tried for obscenity in Cleveland.

On this rather busy visit, Davis was also having an affair with the sister of his pianist on the Ascenseur sessions, Jeanne Urtréger. “He was obsessed

by sex, not by women,” she has said. “But when he was with me, he was with me.” During that tour, Davis wore her scarves on stage as keepsakes and would use her brother to address the scribbled postcards he’d send back to Paris.

Sex, jazz, Paris, cars, murder – the ingredients here are intoxicating and have fuelled the romantic imagination for 75 years ever since, cementing the New Wave as a movement, an attitude, a mood, a philosophy. It’s all there in the images of Ascenseur pour l’échafaud, and in the music, as well as in the mythology and mystique that surrounds the creation of both.

“I get asked for that sound all the time,” says Barker. “Our job as film musicians is, I believe, to get to the emotion that the director wants for that character and in that scene and the use of silence and spaces is just as important – that’s something Miles instinctively knew playing on Lift to the Scaffold.

“It’s a less-is-more approach that has become emblematic of a style, a shorthand for an emotion and an atmosphere, and it’s incredible to think that this was its first appearance – I’m not sure it has ever been bettered than in those moments, that night of improvised recording so many years ago. And it’s amazing to realise that this music – this sound and the message it conveys – is something people still crave today.”