European cinema lost one of its most glamorous and emblematic stars last

week with the passing of Italian actress Monica Vitti.

Through her work with director Michelangelo Antonioni, Vitti came to symbolise all the enigma and sexy sophistication of 60s arthouse film, her performances in his ‘alienation trilogy’ of L’Avventura (1960), La Notte (1961) and L’Eclisse (1962) cementing her as, to extend the famous description of British arts presenter Joan Bakewell, the tortured existentialist’s crumpet.

More importantly, my grandpa might have had an affair with her in the 1960s.

I only found this out almost exactly two years ago, when my grandma died in February 2020, and at the shiva after her funeral, various family members were reminiscing about my grandparents’ marriage, which had appeared rock solid to everyone even long after grandpa had died, in 1993. “She wasn’t happy about Monica Vitti though,” said my great aunt with a frown.

What? I had never known it, but my grandfather had somehow been involved with the financing of the 1966 film Modesty Blaise, for British Lion and he began visiting the set where Monica Vitti was playing the British

super spoofy spy under the somewhat unlikely direction of Joseph Losey.

Apparently, grandpa visited the set a lot, becoming quite obsessed with Ms Vitti. He would disappear to Wales (my mother seems to remember) where it was being shot which sounds weird because, if you knew my Jewish East End grandpa, Wales in the mid-60s wasn’t really his natural habitat.

I can’t find evidence of Modesty Blaise shooting in Wales but there are stories that Antonioni chaperoned his muse around Shepperton and London to such an extent that Losey found it difficult to direct her and, years later, her co-star Dirk Bogarde even complained about her being one of the worst leading ladies he ever worked with. Maybe it was my grandpa’s fault? Certainly grandma suspected him of having an affair with the Italian siren and eventually banned him from going on the shoot.

According to my great aunt: “Your grandma went with him to the premiere and kept a very strict eye on him, I can tell you. Glad to see the back of Monica Vitti, she was.”

I was flabbergasted by this tale. First of all, that grandpa might ever have had an affair with anyone had never crossed my mind. Secondly, I had no idea he was ever involved with movies, let alone one involving Monica Vitti.

Not that there would have been much discussion of urban alienation, Italian cinema or the British work of Joseph Losey around our Friday night dinner table in 1980s north-west London. But apparently, grandma banned all talk of Monica Vitti thereafter, and it was never mentioned again. At least not until her funeral. Oh well.

Anyway, not that this has much to do with paying tribute to Monica Vitti, but it’s a rare personal anecdote about her, because very few people can claim to

have met her, certainly not in the last 20 or so years when she became reclusive and coping with Alzheimer’s.

Obviously, that’s not how one wishes to remember her and the magic of the movies is that we never have to, because she’s immortalised as this beacon of icy, impenetrable European elegance by almost everyone – except my grandma, of course.

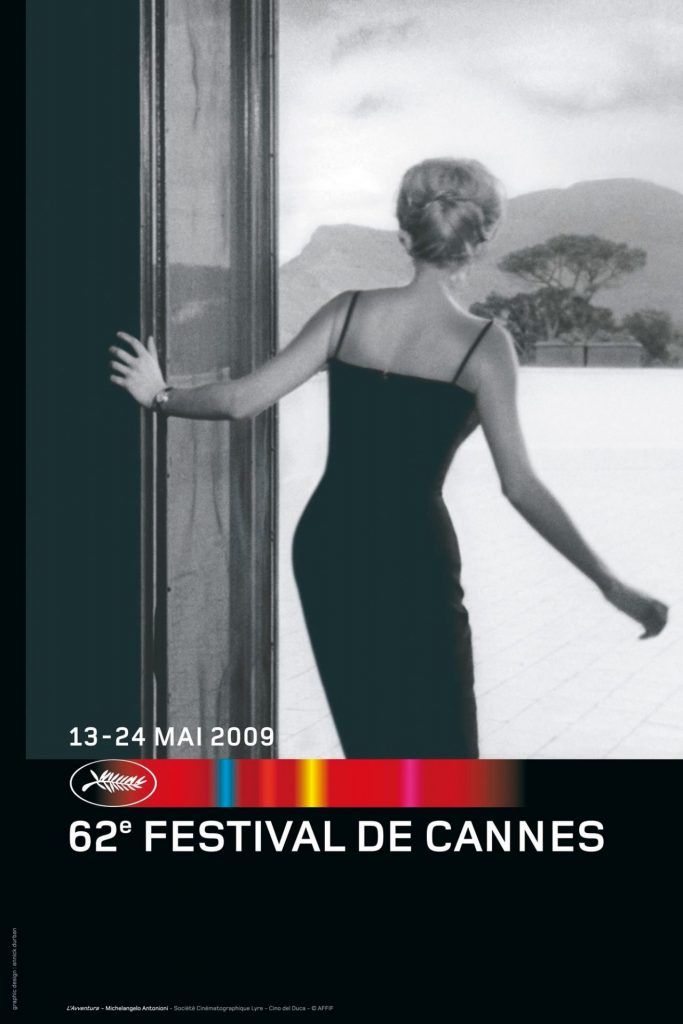

Vitti adorned one of my favourite Cannes Film Festival posters, from its 62nd edition in 2009, with a still from L’Avventura which won the Jury Prize there in 1960 and which I saw in a beautiful restoration at the festival that year, a film of such delicate yet seductive mystery and shot in the Aeolian Islands and Sicily, locations which I’d visited myself on my honeymoon a couple of years earlier, quite unaware of what my grandma would have felt about that.

Cannes re-issued that image, so alluring even in silhouette, her face turned from us but gazing out on infinite possibilities, posting on Instagram last week and paying tribute to Vitti’s “dazzling talent, grace and radiance” and calling her passing a “huge sadness.” (They also published a press shot of her publicising Modesty Blaise in a convertible car surrounded by a crowd on the Croisette – I zoomed in but, with some disappointment, couldn’t spot my grandpa anywhere.)

What was it about Vitti that made her such a symbol of her era and of that particular kind of cinema?

Lee Marshall is a renowned journalist who lives in Italy and writes on culture, architecture and cinema. “It annoys me to see her thought of as

just a great ‘cinematic face’ or ‘muse’,” he tells me. “Part of this is probably to

do with the sexist belief that beautiful actresses don’t need to act – Sophia Loren has spoken about this prejudice but Vitti just got on with proving it

wrong: audiences outside of Italy haven’t seen her full range – they don’t

really know for example what a great comic actress she was. You only have

to watch Monicelli’s The Girl With the Pistol or Dino Risi’s That’s How We Women Are – in which she plays twelve different roles – to realise she had a real appetite for comedy and was very good at it.”

Marshall also believes she often outshone the direction of Antonioni himself, even though he would rarely explain, even to her, his lover and

partner, what was going on in any given shot. “She’s hardly just a poster

girl for his brand of bourgeois alienation,” he says. “All you need to watch again to realise this is that 20-second close-up of her in Taormina at the end of L’Avventura. We watch the devastation roll in across her like a raincloud and, for me, the emotion etched on her character’s face says: this is it, this is all I get, I might as well get used to it. It’s a stunning ending but it’s all about Monica Vitti’s face, not Antonioni’s direction.”

As with all the great film stars, there’s always something personal in our connection with them and their movies. We spin stories around them, where we saw them, the effect they had on us and with films such as Antonioni’s with Vitti, they reach deep within our souls and create formative, long-lasting waves.

Rita di Santo is the film critic for Il Manifesto. She was plunged into mourning when I spoke with her last week, as many in Italy were. “She was my favourite actress of all time,” explains di Santo, “and she made my

three favourite movies ever: L’ Avventura, Deserto Rosso and La Notte. All three with my favourite director, Antonioni who we can say really discovered her and what she could do on screen. She was capable of arousing deep and sometimes perplexing reflections and these wonderful films would not have been possible without her.”

For di Santo, Vitti crucially embodied a different kind of Italian woman, too. “In the 1950s Vitti was up against a cinematic world dominated by the 36-24-26 bodyshape of Gina Lollobrigida, Sophia Loren, Silvana Mangano,” she says. “In the 60s she anticipated the sexy iconography of the athletic, tapered woman destined to assert herself in the world imagination by Ursula Andress and Jane Fonda. She had her own style among all these others and I’d say she started a female acting revolution.

“No one more than her has been able to bring to the screen women who seem confused, defenseless, subject to every form of somatization of their

psychological fragility and vulnerable to every unwanted effect of their

internal passion.”

I told you it went deep. If Sophia Loren is the soul of Italian womanhood, and Gina Lollobrigida the body, then Vitti, certainly through those early roles, seems intricately entwined with the post-war Italian female psyche.

Says di Santo: “She had an ability to involve others in what was going on

deep inside, in the turbulence, the sadness of her characters’ lives, maybe in her own life. It was that way she had of seeming so neat and attractive, fragile and sensitive but also sharp and vital. Maybe it was something about that throaty voice. I would definitely say, for me, she was the icon of modern woman.”

Adrian Wootton is a celebrated British film programmer and executive, the CEO of Film London no less and responsible for making the UK a key film hub for international production. But he is also a renowned expert on Italian cinema, shortly to host a new season of Cinema Made In Italy in conjunction with the legendary Cinecitta studios and held at the Cine Lumiere in London’s South Kensington, March 3 – 7.

Responding to the news of Vitti’s passing, the festival has hastily announced it will be screening one of Vitti’s classic performances in its programme.

“I sadly never met her although I did spend an evening with Antonioni once,” says Wootton. “By then, Vitti was a reclusive figure but was talked about with hushed reverence. I’d say she was one of the greatest actresses in Italian cinema, if not world cinema. Obviously, a great beauty but it was that alluring, magnetic, mysterious quality which she made part of her unique screen presence and which she then evolved, with such ease, into being a magnificent comedienne.”

For Wootton, the collaborations with Antonio live on and remain strikingly

relevant reflection of modern life, even now. “She’s magnificent in those movies, right at the challenging, modernist edge of European cinema – they’re ultra-contemporary and still so ambitious and daring in their themes.”

So, if we are to get a quick introduction to Monica Vitti, where would we start, in order to understand quite why she is so significant to modern cinema, to celebrate her contribution rather than mourn her passing?

According to Wootton, Antonioni’s Deserto Rosso (In English, Red Desert) is

the height of Vitti’s ability to be both enigmatic and enthralling so, for him,

that would be essential viewing.

“But a comedy such as Jealousy Italian Style, that’s great fun,” he says. “And I’ve always had a guilty pleasure, soft spot for the daftness of Modesty Blaise.”

Just don’t tell my grandma.