The year is 1556, and Carlos V, Holy Roman Emperor and King of Spain, has had enough. Exhausted by endless conflict – with Protestants, Muslims, France and his own citizens – he announces his abdication in favour of his son Felipe, and says he plans to spend the rest of his days serving God in one of Spain’s remotest spots: Yuste monastery in the mountains of northern Extremadura. The pope of the day called it “the strangest thing that has ever been seen”.

Carlos was born in 1500. His grandparents were Isabel and Fernando, the Catholic monarchs who invented modern Spain, ended the Muslim occupation and sent Columbus to discover the New World, launching an empire on which the sun never set.

Carlos inherited the empire aged 16 and was still a teenager when he was

elected Holy Roman Emperor, becoming the most powerful man on the planet. His jutting jaw – so pronounced that he could barely close his mouth – came from his father’s side, the Habsburgs. He was Carlos the First of Spain, but everyone around here gives him his imperial title: Carlos Quinto (the Fifth).

After a reign of 40 years, he arrived in Extremadura to begin his retirement suffering agonies with gout, and things went badly from the start. According to Geoffrey Parker’s painstaking biography Emperor, nothing had been prepared for his arrival and the apartments he was having refurbished at the monastery were not ready.

To add to the indignity, bad weather made the mountain roads impassable for his mule-borne litter, so he had to be carried on the shoulders of local men to the castle of the Counts of Oropesa in the village of Jarandilla de la Vera, 10km from his destination.

The castle is now a parador, one of Spain’s atmospheric state-run hotels. Set among the boulder-strewn ravines and forests of La Vera, its turrets surround a courtyard lined with palm trees. Carlos stayed here for four months until his apartments at Yuste were ready. It rained most of the time.

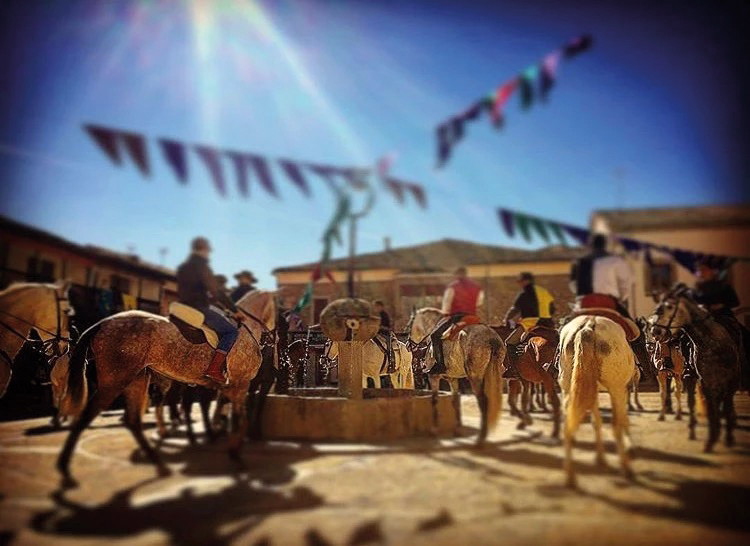

In early 1557, accompanied by a slimmed-down retinue of 51 servants and eight mules, he travelled at last to Yuste. To celebrate the anniversary of that trip in February each year, local enthusiasts dress in Renaissance gear, sling on guitars and lutes, and mount pure-bred Andaluz horses to re-enact the emperor’s final journey.

The Ruta del Emperador takes them from Jarandilla through oak and chestnut forests along ancient paths once used to avoid the bandits who waited to ambush travellers on the main roads. They pause in village squares along the way for musical performances and to share traditional migas extremeñas – bread crumbs fried with garlic and peppers. When they

reach their destination at Yuste there is a proper knees-up.

The Hieronymite monastery was founded in 1402, and for several years before his retirement Carlos had his eye on it as an ideal place to get away from it all. The striking thing about his purpose-built apartments is how small and austere they are.

The sparse furnishings tell the story of an eccentric existence. Carlos became obsessed with the passage of time and spent many hours discussing

his collection of mechanical timepieces with his clockmaker. In the evenings he would read in a specially designed gout chair with articulated leg rests – an early recliner. The imperial bedroom was designed so that when bedridden he could hear the monks performing mass in the adjoining church several times a day. Above the altar hangs a copy of Titian’s Last Judgement, depicting Carlos entering heaven.

The exterior and grounds are more obviously imperial. Formal gardens, Carlos’s pride and joy, surround a rectangular ornamental lake on which black swans glide. Cloisters and balconies lead to magnificent views across the valley. You can often wander here almost alone in the silence, and see it much as Carlos did.

The ex-emperor’s retirement was short and miserable. To his frustration, his letters of advice to the new king, Felipe II, on how to handle the problems of empire were ignored, and he suffered increasingly from unpleasant ailments including convulsions and haemorrhoids. He died in September 1558, of malaria contracted from mosquitoes drawn to the ponds and fountains he had designed to enjoy in retirement.

It was a sorry end, but the inhabitants of the tiny villages of La Vera are understandably proud of their famous, if brief, resident. “It must be the most beautiful place on earth,” they still say. “Otherwise, why would the world’s most powerful man have chosen to live here?”

Peter Barron is an author for Frommer’s Spain. Follow his blog at adventuresinextremadura.com