While I wouldn’t describe myself necessarily as a deep-thinking sort of fellow, there are a number of issues I ponder regularly and to which I

return often despite having little hope of alighting on a satisfactory answer. How do people keep voting for these dim-witted racketeers is one, obviously, and there are several concerning the persistent plight of Charlton Athletic that I won’t trouble you with, but one question, in particular, baffles me more than most.

Why aren’t short stories a massive deal?

Every year for the last decade or more I’ve been insisting to anyone who’ll listen that the short story is the next big thing and every year I am proved emphatically wrong. I am at a loss to explain why.

We’re constantly reminded of how time-poor our lives are and told our concentration spans are shortening. Short stories, self-contained slabs of

fiction generally with a beginning, middle and end, are perfect for the modern world and seem to suit our modern lives.

It’s not just about convenience and the frenetic pace of our interconnected existence, either. Short stories are at the very core of our being. The earliest fiction we experience is in the form of a short story, the fairy tales we’re told before being able to read for ourselves. Go as far back as you like in the history of civilisation and you’ll find people telling each other stories.

During the golden age of print journalism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries the short story was a mainstay of newspapers and magazines. PG Wodehouse established himself this way, with many writers whose names are now long forgotten able to make good livings solely by contributing stories to periodicals.

Some of our greatest writers have produced exquisite short fiction – Ernest Hemingway, Zadie Smith, JD Salinger, Daphne du Maurier – but their short stories have usually been seen as pleasant diversions from the serious business of long-form fiction. It’s extremely rare for an author to be feted as a short story specialist and I can only think of a few: William Trevor, O Henry, Ray Bradbury, Frank O’Connor, Anton Chekov, Flannery O’Connor and John Cheever.

MR James and Edgar Allan Poe aren’t necessarily regarded as short story writers but their spooky tales came in the form of short fiction. Arthur Conan Doyle wrote 56 Sherlock Holmes short stories against four novels while Shirley Jackson’s story The Lottery, first published in the New Yorker in 1948, caused a sensation, effectively launching her career and becoming the most significant modern work of short fiction written in English.

Kristen Roupenian’s 2017 tale of modern dating, Cat Person, also published in the New Yorker, went viral around the world and earned her a $1.2m book deal, but for all I was certain the chickens of my short story evangelism were about to come home to roost, Roupenian has proved to be very much an exception.

Ask anyone in publishing about the lack of high-profile short story collections out there and they’ll shrug and tell you they simply don’t sell. Of

the ones that do emerge, certainly from the bigger publishing houses, almost all are by the likes of Hilary Mantel and Ali Smith, writers already well established by their long-form fiction.

There have been excellent collections by authors who are not household names – Daisy Johnson’s astonishing Fen was a brilliant debut, for example – but generally, the short story is seen as the novel’s poor relation, the “loose change in the treasury of fiction” as JG Ballard put it – a place publishers are reluctant to go.

One exception, however, is Penguin. In recent years, they have been quietly putting out anthologies of stories from a particular country. 2016 brought the wonderful Penguin Book of Dutch Short Stories followed three years later by an equivalent volume from Japan.

Now we have The Penguin Book of French Short Stories in two sumptuous hardback volumes compiled and introduced by the poet, novelist and Professor of French and Comparative Literature at the University of Oxford, Patrick McGuinness. And what a collection it is.

If an authoritative anthology of French short fiction was a terrific idea in itself, handing the job of putting it together to Patrick McGuinness was a masterstroke. Both volumes fizz with the enthusiasm with which he has assembled – and in some cases translated himself – stories that range across centuries and continents to produce a collection well worthy of one of European literature’s prominent nations.

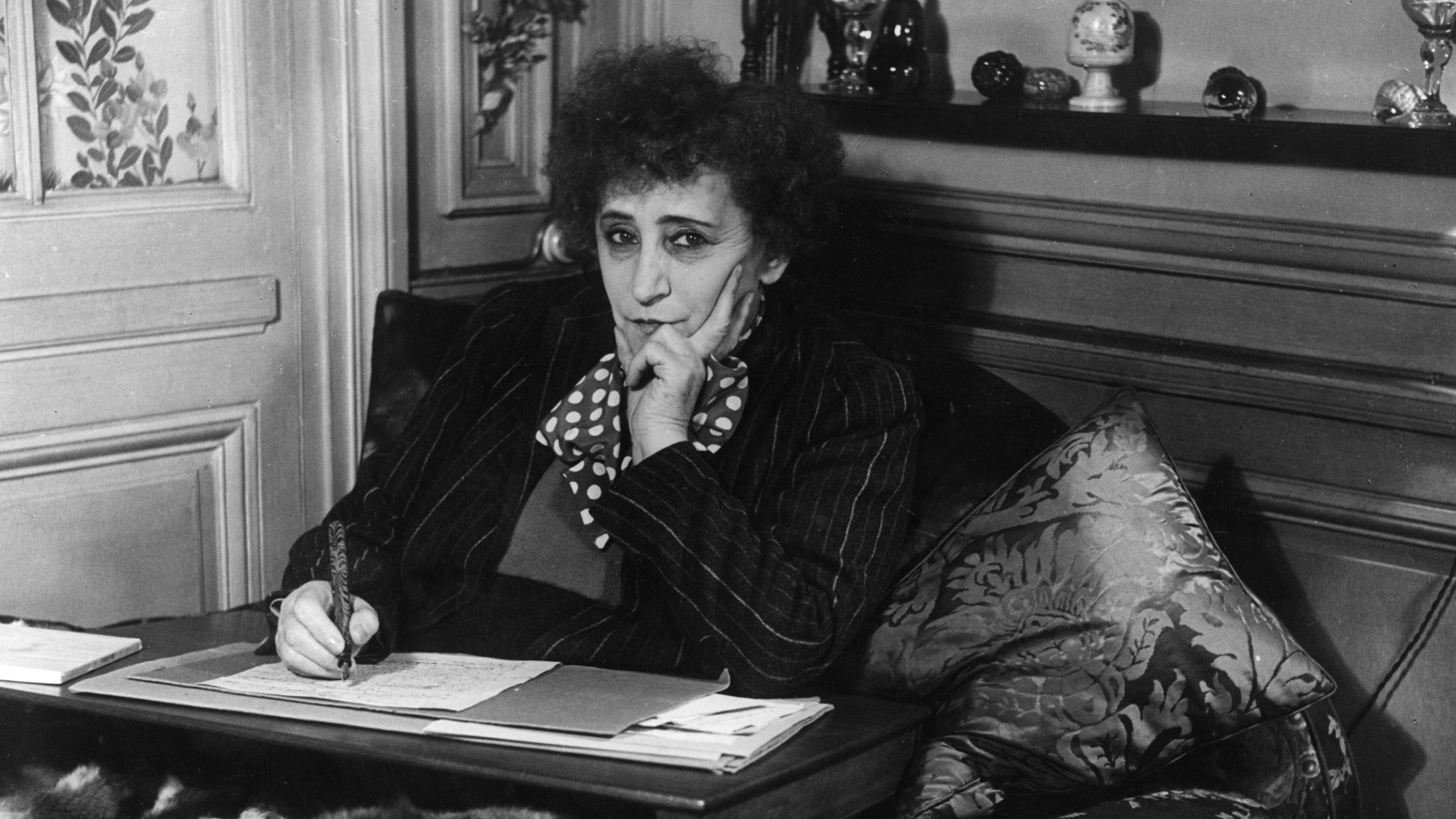

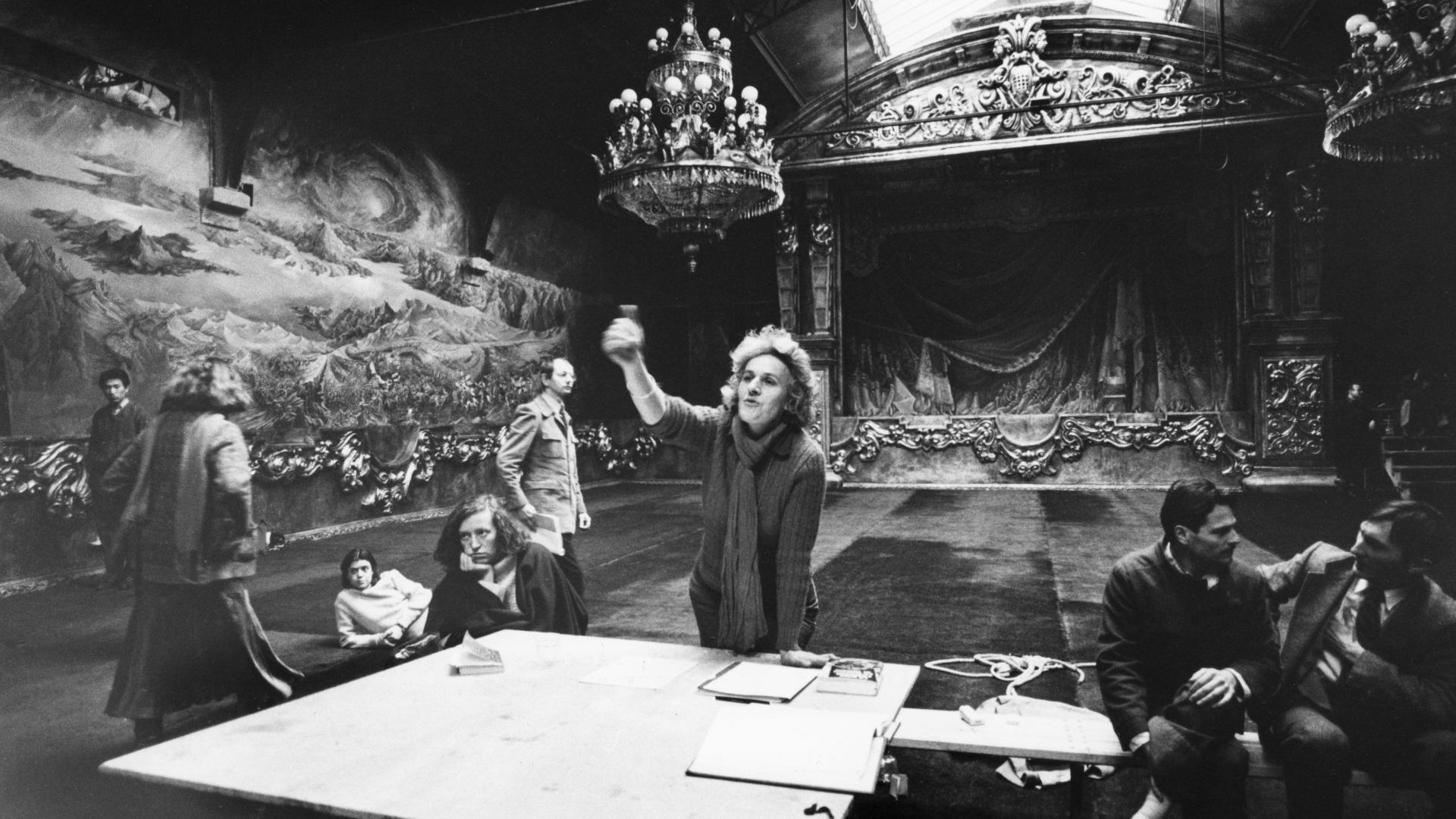

The big names are all here – Balzac, Stendahl, Hugo, Flaubert, Proust, Maupassant, Colette, Duras – but one of the collection’s strong points is in

how many writers are included whose names will be new to most readers. This is no stuffy exercise in academic elitism, it’s a wide-ranging meritocracy of outstanding storytelling.

Where many collections might devise constricting form and format parameters to justify their selections, in his introduction McGuinness makes it clear he has no time for any of that nonsense. He seeks, he says, to provide readers with “many classic examples of the genre” while also introducing them to “oddballs, eccentrics and radical misfits”.

Any lingering fears the collection might be underpinned by dry conservatism are dispelled by the very first story, Philippe de Laon’s The

Husband as Doctor from his mid-15th century collection One Hundred New

Tales (described as both “the first French literary work in prose” and “a museum of obscenities’’). Opening with a sweeping insult of the entire population of the Champagne region, the story soon manifests as an excellent and agreeably filthy long-form joke, a gag as fresh today as it

was half a millennium ago.

McGuinness writes: “These classic tales also show us that once we are together, around a table or in a room, and once we have assured ourselves

of food and shelter, we want stories”. Reading The Husband as Doctor you

can almost hear the murmurs and sniggers as the story builds towards the roar of laughter and thumping of tables at the punchline.

In these early stories in particular, many of which concern the activities, foibles and fallibilities of the extremely wealthy, it’s impossible to shake off the feeling that the short story is literature in its purest form, a natural literary extension of the anecdotes and fables people have always exchanged, satisfying what McGuinness calls our “first non-physical need” for stories.

Passing through the centuries we can track the development of storytelling. While the classic themes of love, redemption, betrayal, hope, tragedy and

heartbreak remain consistent, the stories grow more experimental and subtle, breaking off into genres. Readers will find tales of fantasy here, crime stories and narratives of the supernatural as well as modern realism and colonial voices bringing their lived experience to literature.

McGuinness includes some radical experiments. The early 20th century “three-line novellas” of Félix Fénéon represent the most concise distillation of the format, presenting news snippets from the papers practically verbatim, the story being as much about what isn’t said as what appears on the page.

“In front of the druggist who was her lover, a young lady from Toulon killed herself with a bullet to the heart,” reads one in its entirety.

The true art of the short story lies in this concision, provoking the imagination as much as sating it, brevity having us devise almost as much of the story ourselves as what we read on the page. While lamenting the format’s status as literary “loose change”, Ballard valued the short story as “coined from precious metal, a glint of gold that will glow for ever in the deep purse of your imagination”.

Emile Zola’s Death by Advertising might have been written well over a century ago but slips perfectly into a modern mind assailed constantly by rampant consumerism as we follow Pierre Landry through a life dictated by an unshakable trust in advertisements.

“He followed them blindly whenever he had a decision to make and he would never buy or do anything that hadn’t been warmly recommended by the publicity men”, writes Zola, a philosophy that turned his home into “a repository for every crackbrained invention or shoddy article on sale in Paris”.

Stretched out to novel length the story would be impossibly tedious but the concision of the short story maximises the impact of Zola’s story while making us question our own susceptibility to commercial seduction.

The 43 stories contained here might be a considerable investment at £60 for the pair of volumes, but they represent far more than a selection assembled from within the borders of a single nation. This will surely turn out to be the definitive anthology of French-language short fiction (there’s no Camus, Sartre or Simenon but their absences are for copyright reasons rather than radical editorial stance), but more than that, The Penguin Book of French Short Stories is a perfect example of what makes short fiction so much more than

gallimaufry dashed off between novels.

McGuinness writes in his introduction: “The question is not ‘what is a short story?’, but ‘what can a short story be?’” and it’s hard to imagine any more definitive answer than the one contained in these two volumes.

The Penguin Book of French Stories is edited by Patrick McGuinness and published in two volumes by Penguin Classics, price £30 per volume