In August 1978, I went on holiday to Crimea with Mikhail, my elder brother. As soon as we arrived in the village we were staying in, which was near the town of Sudak, we went to the library to see what they had. In a one-storey brick building, a young librarian signed us up as temporary members and with a sly smile mentioned that they had the two issues of Moscow magazine that contained Mikhail Bulgakov’s famous novel The Master and Margarita. We were interested – but in a twist which Bulgakov himself would have approved, the librarian then explained that the magazines were out on loan and we would have to join the queue. When our turn came we could borrow the magazines, but for one day only.

There were five readers in front of us in the queue – all from the Sokil holiday resort – a complex located close to the sea, near an ancient Genovese fortress and used exclusively by employees of the Soviet police and their families.

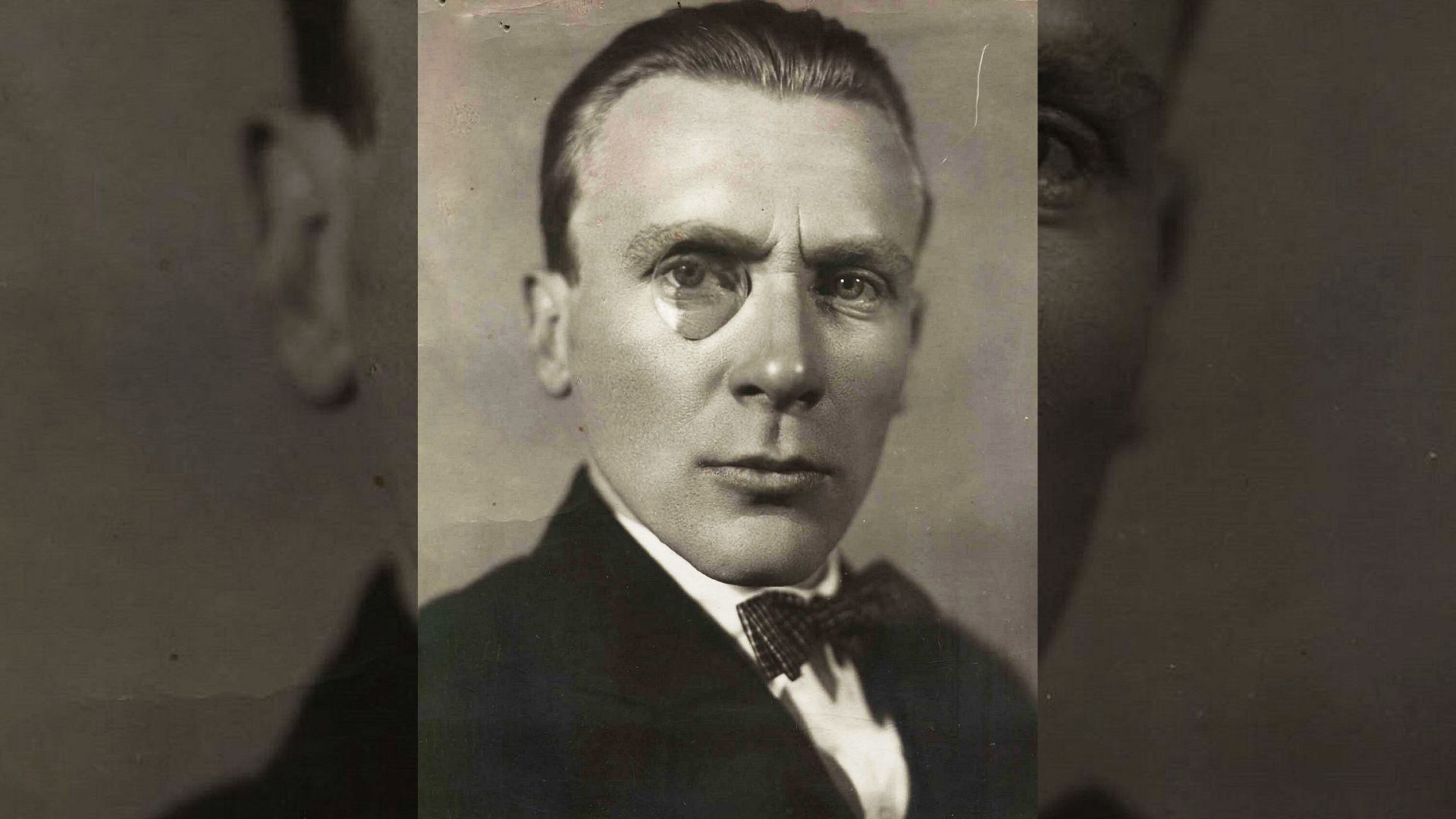

I was 17 years old and had already heard legends about Bulgakov. I had seen the house on Andriivsky Descent in Kyiv, where he had lived until 1919, and it had already piqued my interest. He was a legendary writer, his reputation only enhanced by the fact that his work was notoriously hard to get hold of – much of it had only ever circulated as Samizdat. The Master and Margarita was only made available in 1967 and even then in censored form.

Five days later, we were finally able to borrow the magazines and start reading. We read all day and part of the night, and by the end I had become a full-scale Bulgakov fanatic, one of hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of fans throughout the Soviet Union and beyond. I realised for the first time that in the USSR writers wrote not only boring, realistic prose but also stories completely free of ideology – wild fantasies of magic and devilry.

The plot of The Master and Margarita is almost impossible to describe. It is a swirl of interlocking characters and stories that jumps around in place and time, the combination of fantasy and humdrum normality making it an early example of magic realism. Bulgakov conjured up a story that involved not only Soviet functionaries and bickering literary scholars, but also a talking cat, Pontius Pilate and even the Devil himself. The story is set primarily in Moscow, which Bulgakov turns into a surreal playground for the Devil’s entourage, who drive the city into a state of pandemonium. In a dangerous political twist, these unwanted visitors are depicted as being more powerful even than the Communist Party itself.

The writing is dreamlike, ironical, and from a Soviet perspective, deeply subversive. The talking cat, an associate of the Devil, is like a character from an evil Alice in Wonderland. Says the cat: “‘Actually, I do happen to resemble a hallucination. Kindly note my silhouette in the moonlight.’ The cat climbed into the shaft of moonlight and wanted to keep talking but was asked to be quiet. ‘Very well, I shall be silent,’ he replied, ‘I shall be a silent hallucination’.”

Photo: Gérard Julien/AFP/Getty

What must the Soviet censors have made of such strange, ambiguous stuff? They surely can’t have been impressed by Azazello, another of the Devil’s associates, who goes about his business in the precise manner of a 1930s NKVD (secret police) heavy: “Punch a man on the nose, kick an old man downstairs, shoot somebody or any old thing like that, that’s my job. But argue with women in love – no thank you!”

Bulgakov’s fantastical approach – a sharp deviation from the authorised Soviet style – became his trademark and it characterised novels such as The Fatal Eggs and Heart of the Dog, written in 1924 and 1925 respectively, both wild flights of imagination that come close to science fiction. It was perhaps inevitable, then, that Bulgakov’s works should be banned by the Soviet authorities.

Reading The Master and Margarita for the first time, I marvelled at Bulgakov’s courage. I saw him as a brave writer, not afraid of the dictates of the party or of censorship. I didn’t know anything about his real life. I only knew that he was born in Kyiv, studied at the medical faculty of Kyiv University and lived at 13 Andriivsky Descent, where his family rented an apartment on the second floor of a two-storey building. But, as I was to learn, there was more to it than that.

In 1991 – the year of the collapse of the USSR – Bulgakov’s former home in Kyiv became the Mikhail Bulgakov Museum, and a bronze lifesize sculpture of the writer was placed on a bench nearby. Like other public sculptures in Kyiv, the statue of Bulgakov is now protected from possible Russian rocket and artillery attacks by a wall of sandbags. However, he is completely defenceless before a group of Ukrainian intellectuals who have been demanding that Bulgakov “be thrown off his pedestal”. They insist that he was a Russian imperialist writer. They want the museum closed down.

The museum is still open and working. Visitors are shown around and told about the “Kyiv” and “Moscow” periods of Bulgakov’s life. Recently, museum staff have been writing articles and issuing public statements defending both Mikhail Bulgakov and the museum itself from political attacks.

Oksana Zabuzhko, one of Ukraine’s best-known writers and essayists, was the first to make a public attack on the late Bulgakov, or rather, on his status as a “Kyiv writer”. She did this rather elegantly by publishing an article about the house on Andriivsky Descent, popularly known as the “Bulgakov House”. In her article, published in 2015, she describes the real owner of this house from whom the Bulgakov family rented an apartment. Vasil Listovnichy was a well-known architect, engineer and honorary citizen of Kyiv – a representative of the city’s Ukrainian elite. Relations between him and his tenants, the Bulgakovs, were probably not cloudless. And yet Bulgakov portrayed Listovnichy in the novel The White Guard as bilious and deeply unpleasant.

Not much is known about Listovnichy, but he was clearly an impressive person. During the first world war, he was promoted to colonel. He taught engineering, wrote textbooks, and had an extensive library, which he allowed his tenants to use. During the civil war, he served in both state institutions of the Ukrainian People’s Republic and in Bolshevik institutions. But by 1919, the logic of the revolution had taken hold, meaning that his achievements and his standing counted against him. He was arrested as a class enemy by the Bolshevik secret police and killed as he tried to escape while being escorted to prison. This was the man Bulgakov had portrayed so damningly.

Zabuzhko’s article set the stage for further critical appraisals of Bulgakov, and as the extent of Russian atrocities committed against Ukrainians became clear, the focus on Bulgakov’s character intensified. In August 2022, the well-known literary critic and professor at the Kiyv-Mohyla Academy, Vera Ageeva, gave an interview on Public Radio, turning her attention to his novel The White Guard.

“Why is Bulgakov still in the Ukrainian school curriculum?” she asked. “He is not taught anywhere in Europe. Bulgakov wrote the most dangerous, anti-Ukrainian novel. The hatred of Ukrainians and the desecration of the Ukrainian People’s Republic that we see in The White Guard can be found nowhere else. He is a native of Kyiv, but this does not prove that he is a worthy Ukrainian. He described his Russian Kyiv. And he wrote about the Ukrainians as if they were dirty beasts, threatening ‘the beautiful world of the Turbins’. Leaving Bulgakov in the school programme is like displaying portraits of people who broke into your house, spat on it, and smashed it up. This is a question of national identity, which should be dealt with by the SBU [Ukrainian Security Service], full stop!”

Two weeks later, Ukraine’s National Union of Writers issued a statement in which it demanded that the Bulgakov Memorial Museum be closed and that the premises be turned into a museum dedicated to the Ukrainian composer and choral director Oleksandr Koshyts. True, this statement caused a backlash among many Ukrainian intellectuals who demanded the liquidation of the National Union of Writers – an organisation founded by the Soviet Union’s communist authorities.

Ukraine’s minister of culture, Oleksandr Tkachenko, has since stated that the Bulgakov Museum will not be closed. Whether Bulgakov’s works will continue to be studied in Ukrainian schools is still the subject of debate.

What did Bulgakov do to attract such opprobrium? At the heart of it was his sense of being a loyal citizen of the Russian empire, which was being destroyed before his eyes in Kyiv by the raging civil war. He was horrified by this destruction and was as afraid of Bolshevism as of the Ukrainian national movement. After the civil war he moved to Moscow, where he lived until his death in 1940.

For a Soviet author of that period, Bulgakov was one of the lucky ones. By the end of the 1930s, hundreds, if not thousands, of Soviet artists had been sent to prison camps. Many of them had been shot, like the remarkable writer Boris Pilnyak. A whole generation of Ukrainian poets, authors, critics and playwrights was annihilated, shot dead at the Sandarmokh camp in Karelia.

Bulgakov survived this fate, even though he was a dangerously individual experimentalist, a representative of the bourgeoisie, a former doctor in the Ukrainian army from which he deserted, fleeing with the White Army to the Caucasus.

Unlike The Master and Margarita, The White Guard is a realistic and semi-autobiographical novel about the loss of a treasured home and a treasured way of life. It is set in Kyiv during the civil war and describes the tragedy of the Russian intelligentsia. Bulgakov frequently alludes to the comfort and beauty of his domestic world – a world destroyed by the revolution. Yes, Bulgakov writes about “Russian Kyiv”, about the catastrophe that the Russian aristocracy and Russian officers had to endure. He writes about the death of tsarist Russia. This is exactly what Joseph Stalin liked about The Days of the Turbins, the play Bulgakov wrote based on the novel, first staged in the Moscow Art Theatre in October 1926.

It was a huge success with audiences, but it also provoked fierce political criticism. Bulgakov was accused of glorifying the counter-revolutionary white movement, as well as holding bourgeois views that were counter to the interests of the proletariat and of socialism. In 1929, the theatre withdrew the play from the repertoire, and Bulgakov found himself in serious financial distress. His books were banned and he had been able to survive in Moscow only because of fees earned from the performance of his play.

Left without a livelihood, Bulgakov did something very dangerous and highly controversial – he wrote a letter to the Soviet government, asking to be allowed to go abroad with his wife.

“Now I am destroyed,” he writes in this letter. “This annihilation has been greeted by the Soviet public with complete joy and is called an achievement… I appeal to the humanity of the Soviet Government and ask that a writer who cannot be useful at home, in the fatherland, be generously set free. If, however, what I have written is unconvincing, and I am doomed to lifelong silence in the USSR, I ask the Soviet Government to give me a job in my specialty and to send me to the theatre to work as a full-time director.”

Twenty days after sending that letter, something so extraordinary occurred that it was like a scene from one of his books. The phone rang in Bulgakov’s apartment. It was Stalin. He was calling about the letter. He asked the startled Bulgakov whether he really wanted to go abroad. Bulgakov replied that he had thought a lot about emigration but had concluded that a writer could not live outside his homeland. Stalin advised him to ask for a job at the Moscow Art Theatre, where Bulgakov had previously been refused employment. This phone call seems to have moved Bulgakov away from the edge of an abyss. He was hired to work in the theatre, clearly on Stalin’s personal instructions. Also on Stalin’s instructions, The Days of the Turbins was returned to the stage of the Moscow Art Theatre and regularly appeared in its repertoire. Bulgakov’s state of mind improved.

Stalin loved this play about the destruction of all that Bulgakov had held dear. He went to see it several times. “The Days of the Turbins is a demonstration of the all-destroying power of Bolshevism,” he wrote in a letter to the Soviet playwright Vladimir Bill-Belotserkovsky. But the original book remained banned.

Did Stalin really appreciate Bulgakov’s talent? It is more likely that he enjoyed playing with a remnant of bourgeois life, keeping Bulgakov alive and employed, but struggling. In this way he became part of Stalin’s “collection” – an example of a defeated class enemy who humbly accepted his fate, caged in his Moscow apartment. But without Stalin’s interest, he would surely not have survived 1937-1938 – the most intense period of Soviet terror – meaning he never would have written The Master and Margarita, completed in 1940. After Stalin’s phone call, no one dared touch him.

The Mikhail Bulgakov Museum is still open three days a week, Friday to Sunday. On its heated veranda, you can still drink tea with jam, as was customary for the Bulgakov family and for the fictional Turbin family in The White Guard. The museum continues to host literary meetings and musical evenings. Bulgakov fans regularly gather in the museum to make camouflage nets for the Ukrainian army.

Would Bulgakov himself have joined them if he were alive today? I think he would. I can easily imagine him becoming a typical, individualist citizen of post-Soviet, independent Ukraine. He would have enjoyed the lack of censorship. I think he would have defended the Ukrainian way of life against the Devil, who now inhabits Moscow. Bulgakov would have wanted to protect the comforts of Ukraine, which have so often surprised the Russian invading forces, and which, wherever possible, they steal and try to take home with them.

Andrey Kurkov is the author of 19 novels, including the bestselling Death and the Penguin.