First, forget the small boats. They grab headlines but have very little to do with net migration figures. If we are going to have a national conversation about immigration – as Nigel Farage, Jeremy Hunt and even Labour claim to want – what we need to look at instead are the numbers of people entering (and leaving) the UK to work, live or study or to accompany someone coming to do so.

The only question worth asking is: Do these deliver a benefit to the economy because of output, spending and taxes or a deficit via schooling, healthcare and pensions? This is why the current election conversation on immigration is so frustrating. It is based on just reducing headline numbers, without caring if that is good for the economy or not.

The conversation need not have begun this way. Current high net migration figures have been fuelled by three one-offs – those fleeing Hong Kong, those fleeing Ukraine and students whose studies in Britain were delayed by Covid.

The next government will almost certainly see falling numbers of immigrants as those factors drop out of the calculations – the figure could well drop down to 250,000 a year again very soon, a rate that most parties could probably live with. Yet they all seem to be fighting to appear the least welcoming to immigrants.

Labour say they will reduce demand for foreign workers by forcing firms to show they are training UK staff first. This at least has the benefit of admitting that there are huge skill shortages in the UK and far too many untrained unemployed, and that immigration is plugging some of those gaps. Yet it does not address the central issue of whether we also need immigrants for the good of the economy.

The Tories, having failed to bring down immigration while in power, now threaten to let the Migration Advisory Committee decide how many immigrants are “necessary” and then the government will somehow “allocate” them to different sectors and jobs across the country. This Stalinist central planning of workers is totally unworkable. It reeks of desperation.

The Lib Dems don’t seem to have much of an immigration policy other than to say that the Home Office shouldn’t handle it, which, given the Home Office’s reputation, is probably a step forward.

Reform wants to limit immigration to the same level as emigration; a one-in/one-out system that turns the Border Force into glorified nightclub bouncers. Reform think the country is “full”; instead it is their heads that are empty.

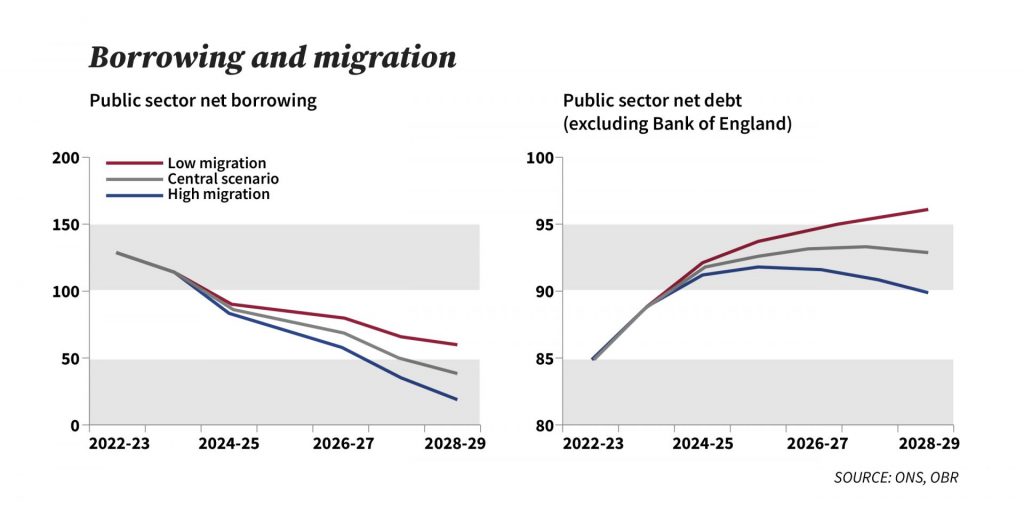

These are the facts about what would be best for the British economy. Before Hunt’s last budget, the Office for Budget Responsibility looked at the issue and found that higher immigration meant a larger economy.

It took the Office for National Statistics’ projection of an extra 350,000 immigrants by 2028/9 and calculated that would mean another £7.5bn in tax for the government – handy as Hunt then promised to spend almost exactly that amount in tax cuts.

Strangely, I don’t remember him thanking immigrants for the wealth they had created. Nor did he mention that his tax cuts would be unaffordable if his government succeeded in slashing immigration.

The OBR took into account the extra government spending those immigrants would need, on health, education and so on and still found a £5bn profit to the government. This makes sense – immigrants tend to arrive after someone else has paid for their early healthcare and education; they come to work and therefore to pay taxes; many retire to their country of origin and therefore place few burdens on the NHS or the pension system.

Those pesky immigrants coming over here and putting in more than they take out also have a decisive influence on the government’s borrowing. Without them, we would be in a far worse position.

The OBR even has a handy chart that takes all the different scenarios into account, which shows that higher immigration would reduce borrowing by £150bn by the end of the forecast period.

As Professor Jonathan Portes from King’s College pointed out in his analysis of the OBR’s work, if the next government succeeds “in reducing migration very substantially below projected levels, it will have a large fiscal cost, with consequent impacts for tax and spending.”

It is shameful then that no one in this election is being honest about the issue. But it helps explain why so many sectors of the economy are pulling their hair out.

Universities have subsidised domestic student fees for years by charging foreign students even more. Without that cash, some may go to the wall.

Agriculture has its own problems with seasonal workers. The care sector is dependent on foreign staff, probably too dependent as it appears to use immigration to hold down wages and costs. In fact, as Portes told me: “If we paid care workers more and treated them better that would make a difference (to immigration), but we would have to pay them from the public purse”.

Hospitality and catering are crying out for more staff, with Kate Nicholls, chief executive of UKHospitality, saying: “While we recognise the need to control migration, this debate cannot be arbitrary and divorced from economic reality.”

Manufacturing industry has been fuming for years about the mess the Tories have made of the apprenticeship system, and limiting immigration too is a double whammy. The reduction in apprenticeships has encouraged firms to employ immigrants but now even that route has been stymied by the government, forcing up the wages firms must pay before they can even apply for a visa. Linking the skills system and the immigration system would help the sector.

The best hope is that we ignore all the electoral posturing and hope for some common sense when the new government is formed. As those one-off factors fall out of the immigration numbers, the total will fall so sharply that the next government might be under less pressure to wreck the economy to keep the media happy. It could use that breathing space to train far more people and develop a consistent and reliable immigration policy that provides the economy with what it needs.

Anything else is just cutting off your nose to spite your face. But even in a general election campaign when the result is almost certainly already set in stone, still no one is willing to say so.