Eighty years ago, all hell rained down on Dresden. Between February 13 and 15, 1945, 772 Allied bombers dropped more than 3500 tonnes of high-explosive and incendiary devices. The entire city centre was destroyed and 25,000 people perished in the resulting firestorm. Vehicles exploded and roads melted as the temperature reached 800°C.

“It was beyond belief, worse than the blackest nightmare,” wrote survivor Lothar Metzger. “Terrible things: cremated adults shrunk to the size of small children, pieces of arms and legs, whole families burnt to death.”

Britain had endured attacks on London, Coventry, Liverpool and many other cities and, as the war swung in the Allies’ favour, German cities were struck, Hamburg perhaps worst of all. But Dresden has somehow become a touchstone for the depravity of seemingly indiscriminate mass bombing and communal terror.

To the Blitz-weary British public, it probably seemed fair retribution, while the doughty Allied airmen who flew the missions were simply intent on victory over an implacable enemy. But the war was essentially won, Germany would surrender three months later. And by then, British prime minister Winston Churchill was already distancing himself from the decision to bomb.

In many ways Dresden was unlucky. “The attack wasn’t out of the blue,” says Peter Johnson, a WWII historian, and director of narrative and content at Imperial War Museums. “Hamburg, Cologne, Berlin. All had been hit. And Dresden, in eastern Germany, was next. Area bombing was a policy agreed in advance between Churchill and his cabinet, and one that air chief marshal Arthur Harris inherited in 1942 when he took charge of Bomber Command.”

Although ‘Bomber’ Harris has since been criticised for his gung-ho military tactics, “to simply blame Harris alone would be to perpetuate a lazy myth,” argues Johnson. In fact the raid was part of a strategy to aid the Soviet advance from the east, requested by Churchill.

“But certainly, what happened ran deep,” adds Johnson. “The delay in the British memorial to Bomber Command [only completed in 2012] was possibly due in part to distaste over Dresden.”

The devastating effect of the raid immediately raised concerns. Pacifists questioned its morality, but even in an era of total warfare, the proportionality of the attack was also questioned by press, politicians and notably the public in Britain and elsewhere. “And as a cultural and architectural capital, Dresden’s destruction seemed to cross an arbitrary line,” adds Johnson.

Adroit politician that he was, Churchill took note, showing he was listening, perhaps because he realised once Germany was defeated the Allies would need to govern its people. That wouldn’t be easy if you had killed half of them and destroyed their cities.

But he was equally aware the only way to take the war to Germany, especially before D-Day, was through the air. “Fighters are our salvation,” Churchill said after the Battle of Britain in 1940, “but bombers alone provide the means of victory.”

Air warfare, even in those far-off days, had to comply with the laws and customs of war. Civilians could not be targeted directly, attacks had to be proportionate with a legitimate military target.

It’s been argued long and hard by both sides over whether Dresden fulfilled those somewhat loose terms. Meanwhile, the argument that defeating Naziism and liberating Europe pretty much held sway.

But is there any truth to the argument that Dresden was retribution for the Blitz? “That’s an easy link to make, but it would be a mistake,” says Johnson. “Nor was it targeted for its architectural or cultural importance. It was a hub of communications and transport. Dresden was simply the next target on Bomber Command’s list.”

Yet the charge of “war crime” fails to be quelled. And it attracts strange bedfellows. Those whose families endured it and pacifists are, disturbingly, joined by modern-day neo-Nazis who call it a crime against the Third Reich. They exaggerate the death toll, deny the Holocaust and use Dresden as rationale for their politics.

Meanwhile as Kriegsschuld, the German word for a sense of collective guilt over the second world war, recedes alongside the rise of the far right Alternative für Deutschland, Dresden is used as justification: “The Allies were as bad as us”.

The specific charge of “crimes against humanity” would not be introduced until the Nuremberg Trials of Nazi officials began in November 1945, but even today there is no treaty specific to aerial warfare. However, our innate negative reaction to assaults on non-combatants from the air is shaped in so many ways by Dresden.

The recent wars in Ukraine and Gaza cannot be put into the same context, but our abhorrence of attacks on civilian housing, schools and hospitals, and our questioning of their legitimacy have been moulded by what we know of Dresden.

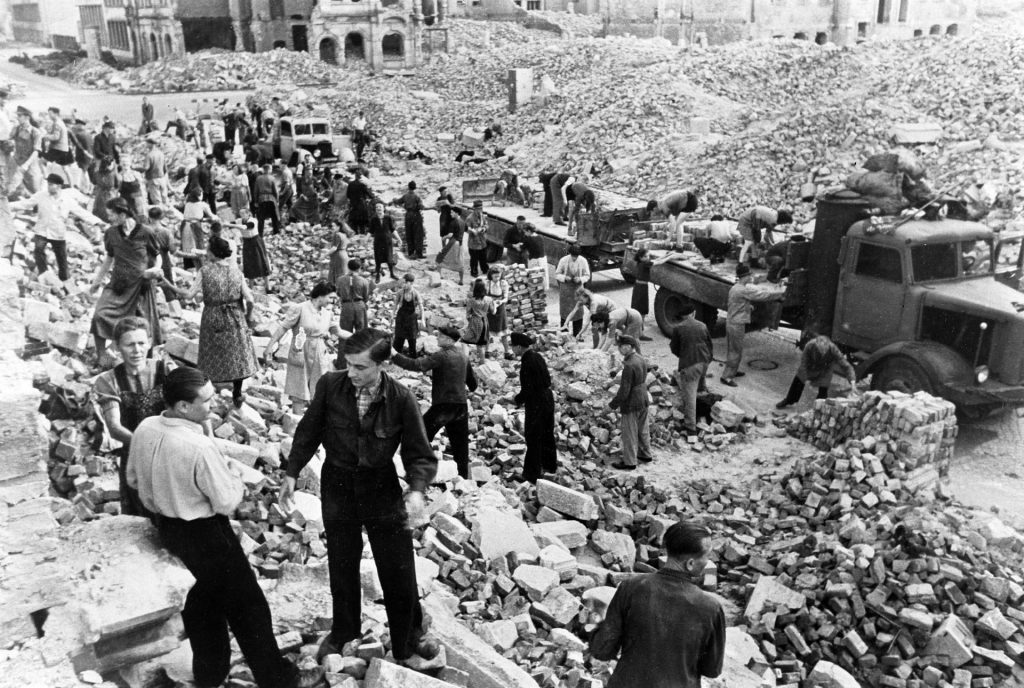

When the city became part of Soviet-occupied Germany, Stalin wanted to preserve its ruins, a symbol to what western imperialism and Naziism could begat. He didn’t get his way. Today Dresden is a city rebuilt – many of its landmarks, such as the Frauenkirche, appear exactly as they once did – vibrant, cultural and a tourist destination once again. A British charity contributed to the reconstruction and Dresden is twinned with Coventry.

But still Dresden remains a moral wartime cause célèbre. “Balancing what we know about fascism, with what we know about the innocents who died here. Well, you cannot put that on a scale and expect the scale to balance, on either side,” says Katja Meyer, granddaughter of Bertha Fischer who died in the raid. “If Dresden happened today, then there would rightly be outrage,” concludes Johnson. “But that is to take Dresden out of the context of its time.”

Maybe conclusions drawn from our own era are always likely to be misperceptions. It goes without saying that the death of any innocent citizen in an act of war is a tragedy.

But perhaps the sheer scale or horror of some cataclysmic events – Srebrenica, the Somme, Guernica and Dresden – means the names themselves will always remain as synonyms for our collective revulsion.