Casablanca shouldn’t really have worked. Intended as little more than a cash-in on the success of Algiers, the 1938 Charles Boyer and Hedy Lamarr vehicle, the script was only half-written by the time production started, and other than the interior of Rick’s Café Américain, the sets were all recycled from other Warner Bros productions.

During filming, Humphrey Bogart told Orson Welles “I’m in the worst picture I’ve ever been in” and even the film’s signature song, As Time Goes By, nearly didn’t make the final cut. Composer Max Steiner was brought in during production and was set to replace the song with one of his own until it emerged that Ingrid Bergman had just cut her hair short in preparation for her next film, making a reshoot impossible. Even Casablanca’s most quoted line, “Play it again, Sam”, doesn’t appear in the film.

What Casablanca does have, however, is heart. Its multinational cast – only three of the 14 credited actors were born in the US – included many members who had fled Nazi Germany, and during the famous defiant rendition of La Marseillaise had genuine tears in their eyes.

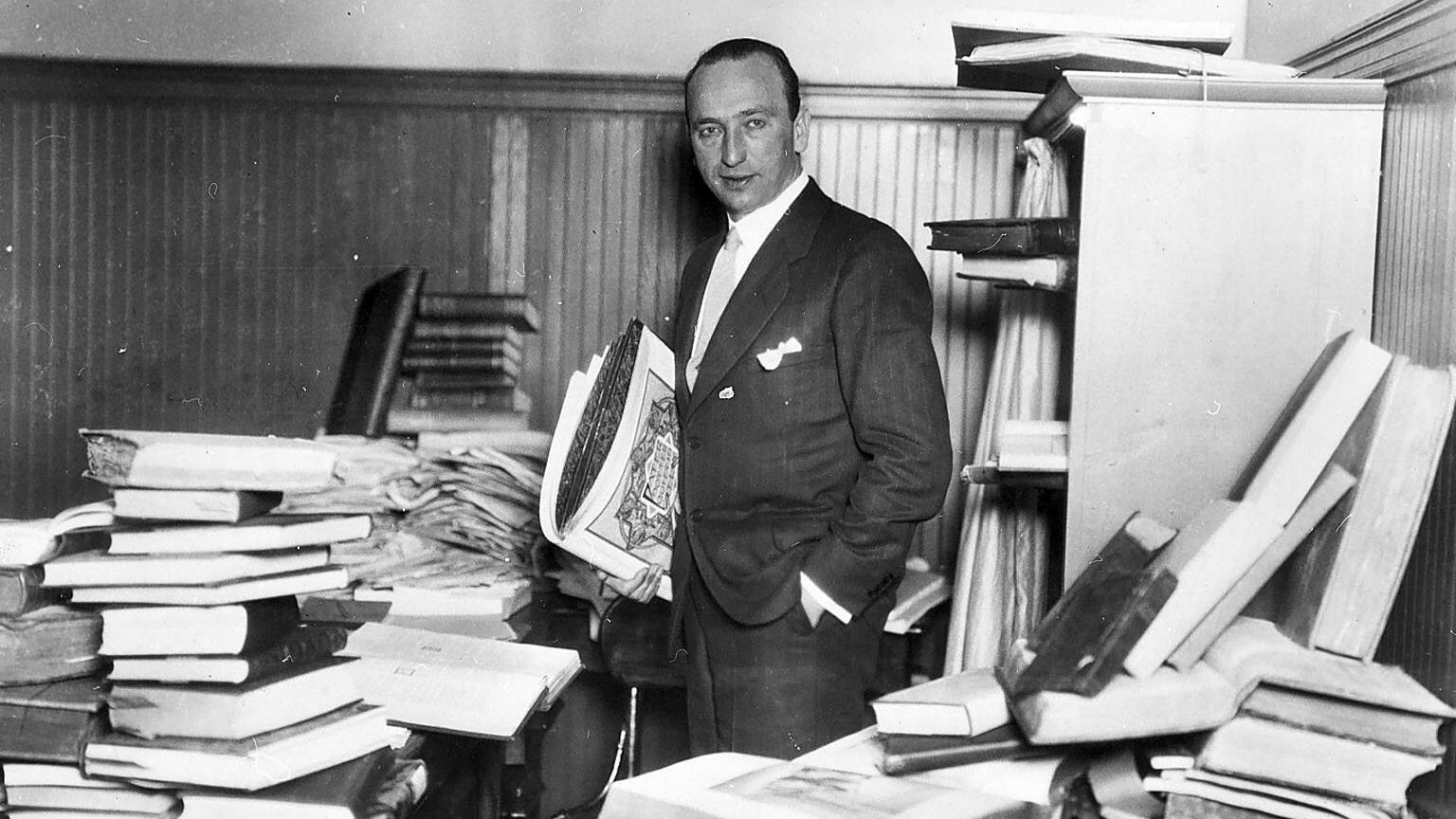

In addition, Casablanca boasted Michael Curtiz in the director’s chair, a fact often overlooked during discussions of why the film came to be regarded as one of the greatest ever made.

His brusque manner, idiosyncratic grasp of English and relentless work ethic often hid the deep emotion he brought to his productions while the sheer number of films he made – he directed or co-directed an astonishing

178, including more than 100 in Hollywood – tended to hide the skill and vision he brought to the cinema.

His polymathic attitude to genres and prolific output mean he is rarely spoken of in the same awed tones as a Hitchcock or Capra, but Curtiz was as much of a craftsman as any Hollywood great.

He moved seamlessly from silent films to talkies, coaxed Oscar-winning performances from a string of great actors, is credited with discovering Doris Day when she was singing with a hired band at a party, transformed Errol Flynn into a swashbuckling screen legend and even managed to direct a critically acclaimed Elvis Presley vehicle in King Creole.

If this versatility was his strength, however, it didn’t help to earn him a place in cinematic posterity.

“What can one say about a guy who could follow up The Egyptian with White Christmas, and jump immediately from Francis of Assisi to a John Wayne western?” asked Charles Silver, curator of a 2011 retrospective at MOMA in New York.

Yet for all his giant leaps in genre Curtiz didn’t just lay a cut-and-paste directorial template over each film he made. He retained some of the German Expressionist techniques he had learned in Europe, yet it’s still almost impossible to identify a Michael Curtiz movie just from watching it. He treated each project on its merits, assessing cast, script and budget and creating the best film he could by demanding the best from everyone involved. Which usually meant a tough time for cast and crew.

“Mike was a pompous bastard who didn’t know how to treat actors,” said James Cagney, who won his only Oscar in Curtiz’s Yankee Doodle Dandy, “but he sure as hell knew how to treat a camera.”

Most famously he clashed with Joan Crawford on the set of Mildred Pierce in 1945, calling the star “Phoney Joany” when he felt she was over-glamourising the title role and wondering aloud, “Why should I waste my time directing this has-been?” Crawford’s career was on the wane, she had barely worked in

two years, but Curtiz’s refusal to indulge his star did the trick – Mildred Pierce earned Crawford her only Academy award for Best Actress.

He may have brought his people success, but Curtiz never learned to accept that not everyone had his extraordinary drive and energy. He slept barely four hours a night and never stopped for lunch, believing that eating in the middle of the day produced fatigue and poor concentration as well as wasting time that could be better spent working.

This intensity and single-minded determination – one story has it that he was once so gripped by an idea that he fell out of a car while writing it up in a notebook, a car he was driving at the time – sometimes led to incidents that would not be remotely acceptable today. In 1926 the flood scene in his Noah’s Ark was hailed as one of the most dramatic scenes in cinema to date, but it came at the expense of some serious injuries to extras. For the climactic eponymous scene of 1936’s The Charge of the Light Brigade, Curtiz strung trip wires across the set to bring down the horses. Of the 125 animals

used in the scene, 25 were either killed outright or had to be destroyed.

Flynn, a renowned horseman, was so furious at the cruelty he witnessed he

physically attacked Curtiz on the set and while the pair would make more films together, they barely spoke again. So grievous had Curtiz’s disregard for the horses’ welfare been that the US Congress passed laws protecting animals used in film-making soon afterwards. Some even credit the formation of the Screen Actors’ Guild in 1933 as being a direct response to

Curtiz’s demanding methods.

There are few clues in his background as to what ignited this relentless drive

and furious work ethic. He was born Manó Kaminer in Budapest, where his father was a carpenter and his mother an opera singer, changing his name to

the Hungarianised Mihály Kertész in his late teens. In a rare interview he once conceded that despite the family’s apparent middle-class credentials money was tight. “Many times we were hungry,” he said.

He graduated from a Budapest drama school and joined a troupe of travelling players, touring Europe performing Shakespeare and Ibsen in various languages. In 1912 he joined the Hungarian National Theatre, directed Hungary’s first feature film – in which he also played the lead – and still found time to compete at the 1912 Olympic Games in Stockholm as a fencer (in 1951 he would direct Burt Lancaster in Jim Thorpe – All American, the story of Native American Thorpe’s experiences at the same games).

Wounded while serving in the Austro-Hungarian army in 1915, he spent the rest of the war making documentaries for the Red Cross and films for Hungary’s leading studio before moving to Vienna in 1919 after the communists came to power in Budapest. By the mid-1920s he was one of the busiest and most respected directors in Europe, his biblical epics, in particular, convincing Warner Bros in 1926 to bring Curtiz, by then nearly 40 years old and with 60 films behind him, to Hollywood as their answer to Cecil B DeMille.

If he didn’t actually revolutionise Hollywood, Curtiz was certainly instrumental in turning it into the behemoth we know today, yet for all his

many talents, achievements and gruelling demands of cast and crew he

remained convinced that the secret to film success was relatively simple.

“The whole motion-picture business,” he said, “is just observation, a good

memory, imagination, a bag of technical tricks — and some luck.”