A pig; three Jews in Germany. This combination of words is bewildering and alarming. It revolves around a statue in a small town and has rekindled the never-ending debate about memorialising the past.

Wittenberg was made famous by one man. Just over 500 years ago, in 1517, Martin Luther nailed his 95 theses to the door of the Schlosskirche, the castle church, calling into question the writ of the Pope, and giving rise to the Protestant Reformation.

Thousands of people from around the world visit Lutherstadt Wittenberg, as it is now marketed. It is easy to get to, barely an hour south of Berlin on the high-speed train. As I saunter around the picturesque Market Square I see a busload of Americans, some Spaniards. In a courtyard a group of bibulous Finns enjoy themselves in a beer garden.

This is classic one-day tourism. There is a Luther house, where he lived for 40 years, there are Luther cafes and there is much Luther merch. Then there is the Stadtkirche, the town church where Luther preached, got married, had his children baptised. And this is where the problem begins.

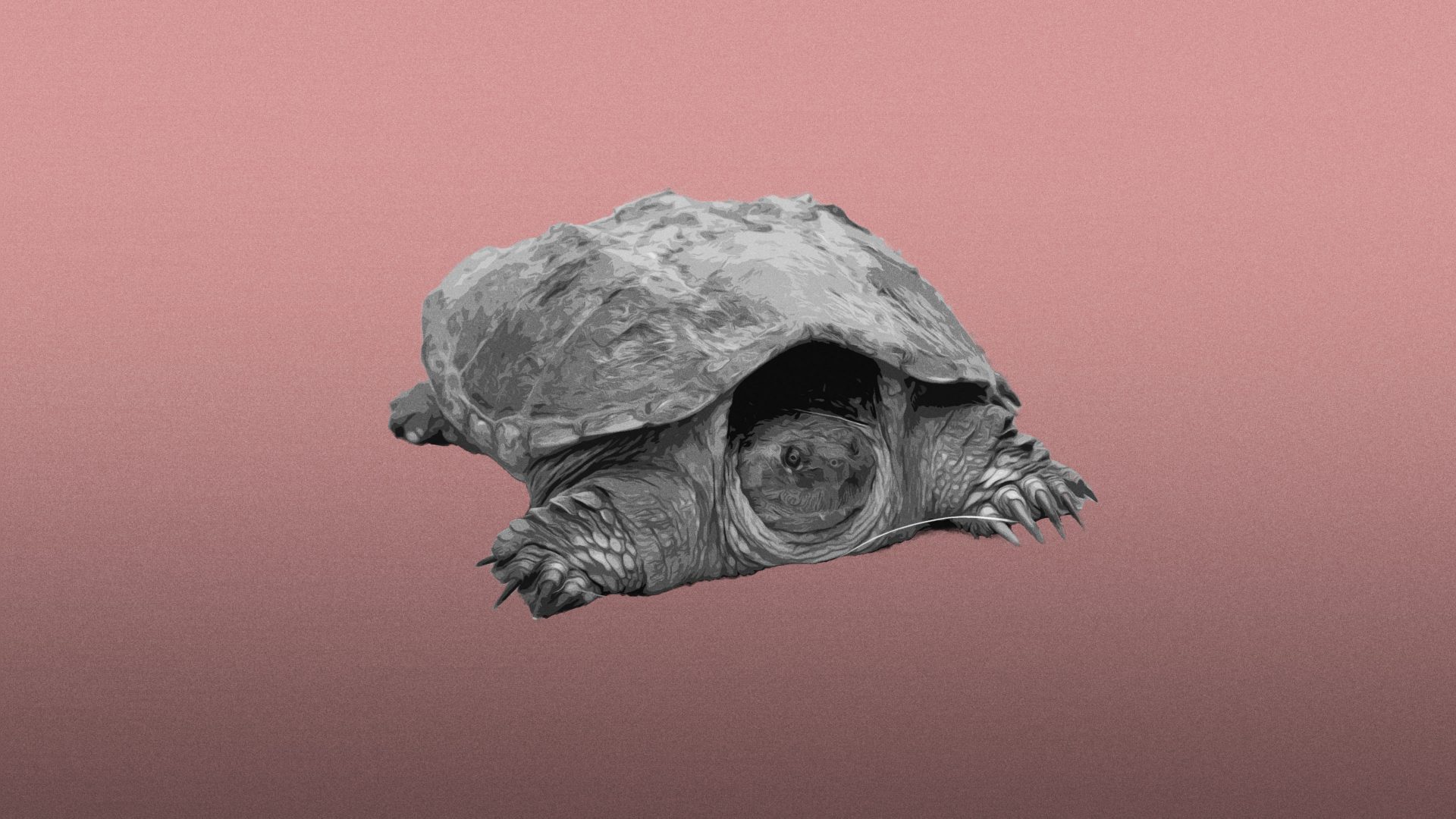

Carved into one wall of the church is a statue that is around 700 years old. It shows a sow with bristly hair and a long snout – and with two people sucking at her teats; they are assumed to be Jews because of their pointed hats – a derogatory symbol of Jewish identity from this period. To the left, there’s another figure – believed to represent a rabbi – who is raising the animal’s tail and peering into its backside.

There are 20 such Judensau or “Jewish pig” statues in churches and historical buildings across Europe. For centuries, few people seemed to care much about this antisemitic trope – either during times of intensified persecution of Jews, or during the odd interlude of relative tolerance. After the war, Wittenberg was in the communist east of Germany, and its medieval times were largely forgotten.

The first heated debates over it took place in 1988, around the 50th anniversary of Kristallnacht. The authorities in Wittenberg unveiled a small memorial to victims of the Holocaust, set into the ground below the sculpture. In 1996, Unesco granted Wittenberg cultural heritage status, one of 50 such sites in Germany.

Since then, the argument has intensified, with ever more insistent calls by some people for the statue to be removed. The local church leadership and the town refused. They cited several arguments – that it belonged to history; that it would be hard to chisel out without ruining the terracotta; and that the hideousness of the imagery had been clearly offset by two plaques denouncing antisemitism.

In June last year, the Court of Justice, Germany’s top appeals court, sided with the locals, ruling that the plaques were sufficient to have turned the “stigma” into a “memorial”. But in April of this year, the federal government’s increasingly irate antisemitism commissioner, Felix Klein, said he would ask Unesco to remove the town’s heritage status.

One of the curiosities of this row is that the sculpture itself is really difficult to find. I walked around the church twice in search of it, and had to go inside to ask a warden, somewhat awkwardly, where I might find it. No problem, he said, it’s all the way up, behind the tree, just outside to the left.

And there it is: four metres high, on the top corner of the church, overlooking an Italian restaurant. You have to crane your neck to catch a glimpse, and even then, thanks to its height and eroded condition, the details are hard to make out. You can only fully understand the horror of the caricature if you look it up online. I would wager most visitors to Wittenberg have no idea about it.

But perhaps that’s not the point. It’s about the principle; but which principle? At a recent conference, the regional bishop suggested that instead of being removed, the statue could be covered up with plastic or some other material. Others – including some in the Jewish community – disagreed, saying it should remain as it is, for all to see; to openly confront the crimes and the hatreds of the past.

This dispute remains unresolved. It goes to the heart of Germany, Nazi crimes, and memorialisation. It touches on issues of local autonomy versus the central government (particularly when it comes to the former GDR). It plays into contemporary battles, everywhere, over the removal of statues.

It also shines a spotlight on the antisemitism that suffused Luther’s own thinking, something that is talked about with much less alacrity.