Welcome to this week’s round-up of the best in culture and the arts. We’d love to hear what you’re enjoying: please send your tips to mattd@tnepublishing.com

BOOK

UNTIL AUGUST

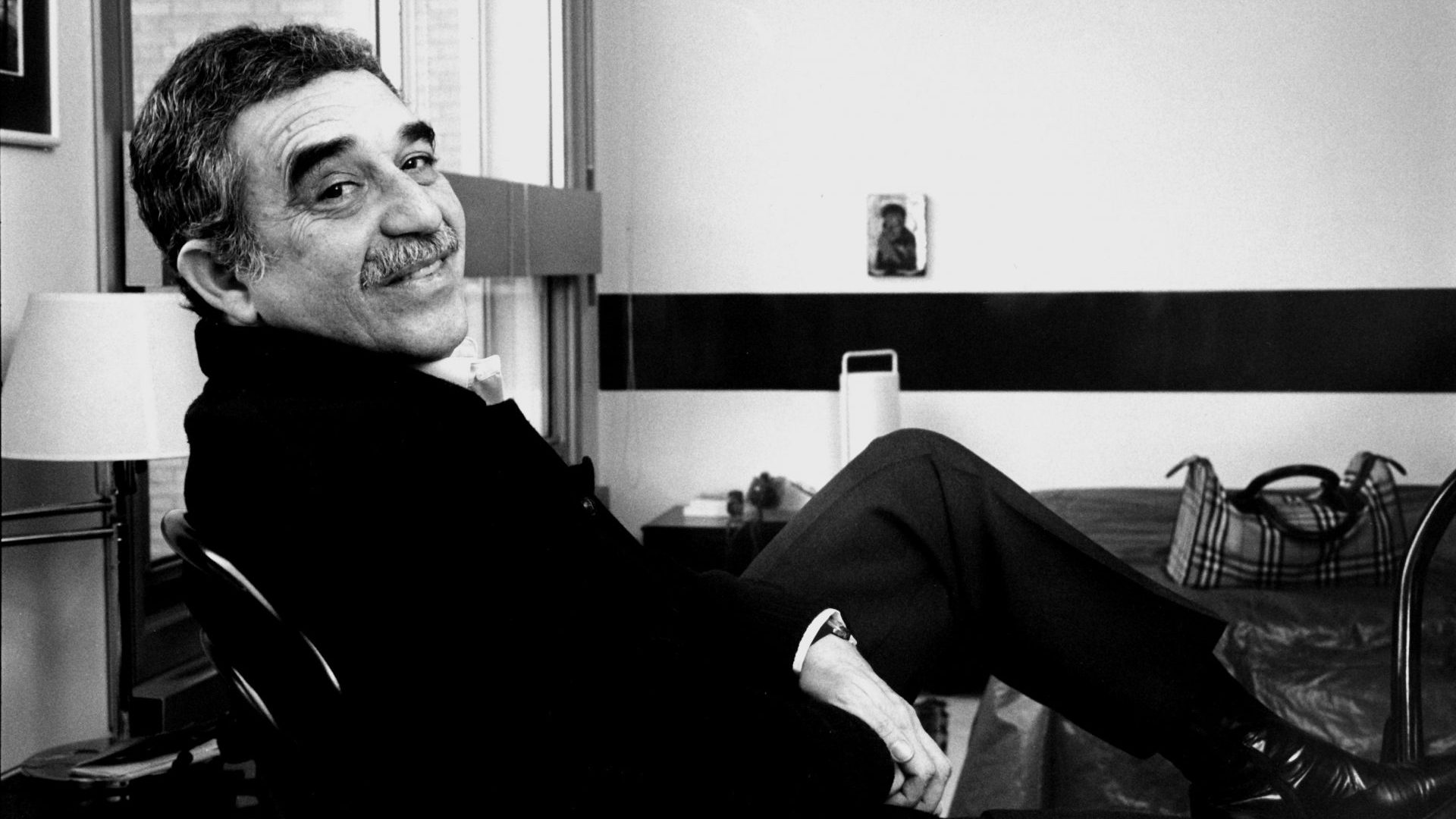

by Gabriel García Márquez

Viking

“Memory is at once my source material and my tool. Without it, there’s nothing”: so said Gabriel García Márquez, whose later years were scarred by dementia, to his sons Rodrigo and Gonzalo. It has been their decision, 10 years after the Nobel laureate’s death, and in contravention of his wishes, to allow the publication of this novella, part of a much longer work upon which he had been working since 1999.

Until August tells the tale of Ana Magdalena Bach, a long-married 46-year-old who makes an annual pilgrimage to an unnamed island to lay a wreath of gladioli on her mother’s grave. After a one-night stand, infidelity with a different man each year becomes part of the ritual (one of whom pretends to be a bishop) – with consequences subtle and otherwise for her home life.

Inevitably, the novella seems slight in comparison to such monumental works of fiction as One Hundred Years of Solitude (1967) or Love in the Time of Cholera (1985). But the language, translated by Anne McLean, retains its sparkle and shimmering suggestiveness: “streets of burning sand beside a sea in flames”; “a good and cowardly heart”; “[she] gripped that hand as if it were the edge of a precipice”; “an orchestra better for dreaming than for dancing”; “a fanciful moon”; “male doubts, which are not easily provoked but almost always infallible”.

The posthumous fate of authors’ unpublished work will always be contentious. Virgil wanted the Aeneid to be burned. It is only thanks to Max Brod’s defiance of his friend’s wishes that we have Kafka’s The Trial and The Castle. The literary world remains divided over the decision of Nabokov’s son to ignore his father’s instructions and publish The Original of Laura in 2009.

Readers of Until August must make up their own minds – but I, for one, am glad that the great Gabo’s children decided to reveal this final gem from their father’s imaginative treasury.

SCREEN

MONSTER

Selected cinemas

Though it bears a superficial resemblance to Kurosawa’s Rashomon – the classic cinematic narrative told from different vantage points – Hirokazu Kore-eda’s exquisite film, set in a lakeside Japanese town, is no less intrigued by the role that authority, hypocrisy and misunderstanding play in concealing the truth as it is by the relativism of individual perspective.

Sakura Ando is excellent as Saori, a single mother worried about her 11-year-old son Minato (Soya Kurokawa), who at one point jumps out of a moving car. Convinced that he is being mistreated by his teacher Mr Hori (Eita Nagayama), she takes the matter to the school where she is stonewalled by surreal and disingenuously formal apologies.

At the heart of the movie is Minato’s friendship with Eri (Hinata Hiiragi), beautifully framed by the director and portrayed by the two young actors. The film begins with a fire and ends with a monsoon; in between, a kaleidoscope of humanity flickers gently but powerfully across the screen, in images that are hugely enhanced by the late Ryuichi Sakamoto’s final score.

BOOK

PRIMA FACIE by Suzie Miller

Hutchinson Heinemann

Two years ago, Jodie Comer’s West End debut as barrister and rape survivor Tessa Ensler in Suzie Miller’s Prima Facie electrified audiences and drew harrowing attention to the failure of the legal system to deliver justice to the victims of sexual assault.

Now, Miller has turned the play into a novel – and to impressive effect. Not surprisingly, the prose is extremely well-paced, so that the reader is already fully immersed in Tessa’s world when it is capsized by the horror inflicted upon her by a man she trusts. The final third of the book is a tour de force that will leave you shaken, enraged and moved. I hope this is only the first of many novels by Miller.

SCREEN

ORIGIN

Selected cinemas

Few non-fiction books of the past decade have made such an impact upon me as Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents (2020) and I was lucky enough to interview its Pulitzer Prize-winning author in the year of its publication.

It seemed inevitable that Caste would be made into a movie – but I did not expect it to become a feature film, in which the writing of the book itself and Wilkerson’s own story became the narrative thread. It takes a director and screenplay of Ava DuVernay’s ingenuity to pull off such a feat, and she does, magnificently so.

As she faces terrible heartbreak in her own life, Isabel (Aunjanue Ellis-Taylor) tries to excavate the layer of prejudice that underpins American racism, German Nazism and the oppression of the Dalits or “untouchables” of India. Beneath all these prejudices is the unifying idea of caste, the “ranking of human value that sets the presumed supremacy of one group against the presumed inferiority of other groups”.

Those who have complained that the movie should have been a conventional documentary have missed the point entirely. It is the dramatisation of Wilkerson’s intellectual work, and its contextualisation in her own experiences, that makes Origin so singular and so powerful.