Pick of the week

The Tempest (Theatre Royal Drury Lane, London, until February 1)

Forty-five years since she paved the way for a new generation of female movie action heroes as Ripley in Alien, Sigourney Weaver makes her West End debut in Jamie Lloyd’s powerful new production of Shakespeare’s final solo-authored play. She is not the first woman to have played Prospero, the exiled Duke of Milan – Helen Mirren, Harriet Walter and Alex Kingston have all wielded the enchanted staff – but her stillness, natural authority and aura of wisdom are a natural fit for the role.

Soutra Gilmour’s staging imagines the island as an eerie metaphysical quarry, with great white and black sails billowing over the performers. As Caliban, Forbes Masson compels our attention with camp psychosis, while Mason Alexander Park is a memorable Ariel, often hovering above the action. Mathew Horne – soon to be seen in the final episode of Gavin and Stacey – also excels as Trinculo, jester to Alonso, king of Naples (Jude Akuwudike)

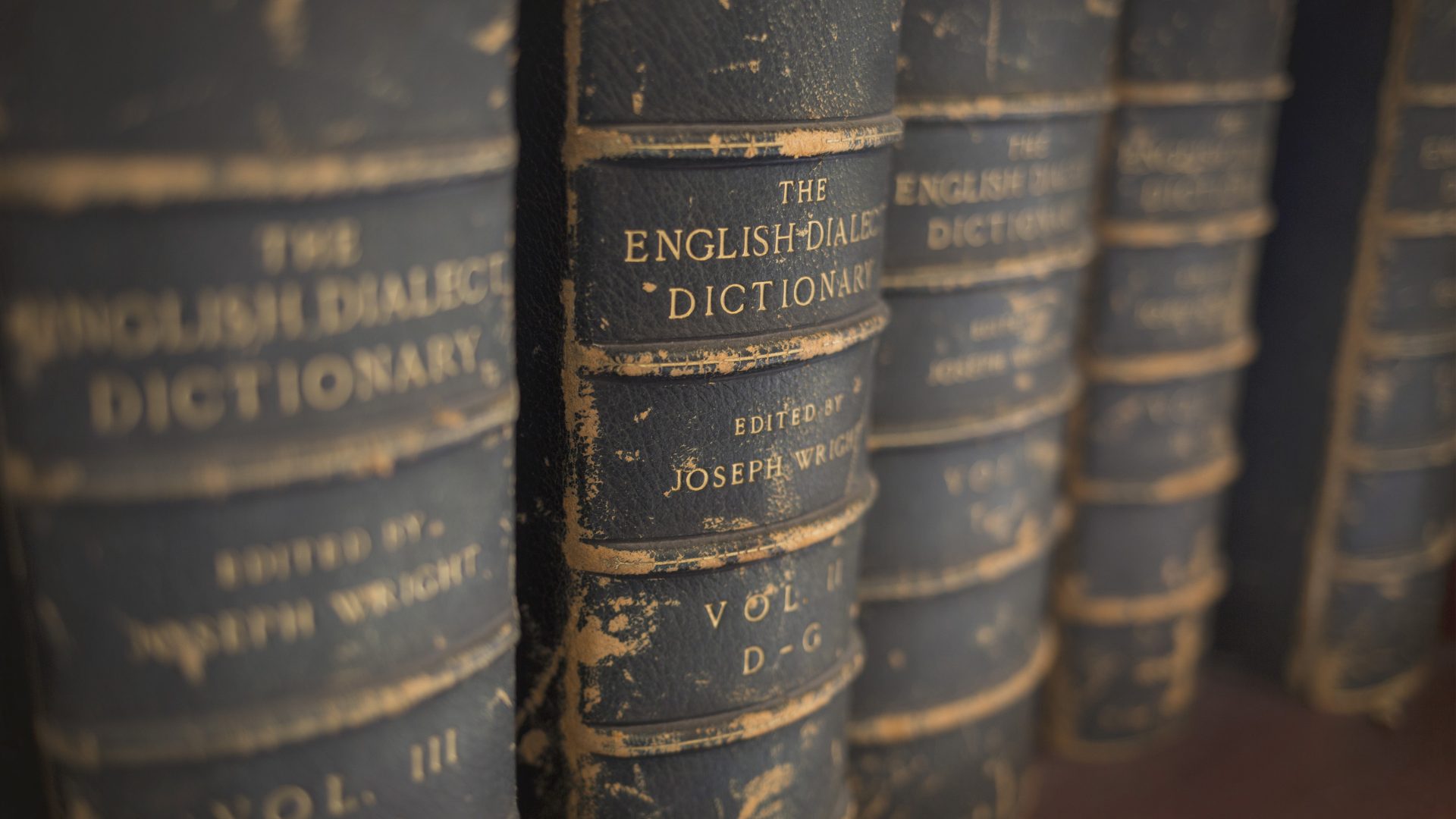

The great Shakespeare scholar, Sir Jonathan Bate, has argued that, at its heart, The Tempest “asks a central humanist question: what do we have to learn from books?” Along with her daughter, Miranda (Maria Huf), Prospero’s greatest treasure is her library. Weaver’s cerebral manner meshes with this theme of deep erudition, alongside Prospero’s command of the sorcerer’s art – inspired, it is often said, by John Dee, court astronomer to Elizabeth I.

Yet the lesson for the learned magus – and for the audience – is that bookishness is no substitute for practical leadership, just as spells are a distraction from true humanity, and indeed mortality. One of the best interpretations of The Tempest that I have seen; and the perfect festive theatre outing.

Film

Queer (selected cinemas)

Prowling the streets of Mexico City at night, to the strains of Nirvana’s Come as You Are, simultaneously dapper and crumpled, William Lee (Daniel Craig) chances upon a crowd gathered around a cockfight – and is thunderstruck by the beauty of a young man, Eugene Allerton (Drew Starkey, excellent).

Lee, an American expat “of independent means”, pursues Allerton with obsessive intent, though unable to conceal his insecurity and self-loathing. They spend time together and go to bed – though Allerton is only intermittently attracted to his besotted admirer.

Desperate to achieve full communion with his lover, Lee suggests a trip to South America to sample yage, the hallucinogenic drug that supposedly enables telepathy. Allerton agrees with a nonchalance that is withering.

Based on the eponymous William S Burroughs novella – begun in 1952 but not published until 1985 – Luca Guadagnino’s mesmerising movie combines his trademark visual romanticism with the grit, sweat and miserable addictions of exiled debauchery. The needle drops are especially good: Prince’s 17 Days, New Order’s Leave Me Alone, Sinéad O’Connor’s cover of All Apologies.

Taking the story further than the original book (which was written while Burroughs awaited trial for the killing of his wife, Joan Vollmer, allegedly in a deranged game of William Tell), Guadagnino allows the two men to succeed in their quest for the drug – which they sample in the Ecuadorian jungle, courtesy of medicine woman Dr Cotter (Lesley Manville). The tribal ritual and psychedelic scenes owe something to The Yage Letters (1963) that Burroughs wrote to his fellow Beat, Allen Ginsberg.

In his introduction to the 1985 edition of Queer, the author wrote that Lee “is disintegrated, desperately in need of contact, completely unsure of himself and of his purpose”. Craig captures this magnificently, commanding the screen: his Lee is full of literary swagger, a .45 pistol on his hip, Malcolm Lowry’s Under the Volcano in his hand.

Yet, in truth, he is a wreck of a man. Strung-out on booze, junk and jealousy, he hides in a world of sensual lawlessness, searching for love and true human connection. An Oscar-worthy performance.

Film

Nightbitch (selected cinemas)

When Amy Adams, a stay-at-home mum, starts to grow fur and pulls a fledgling tail from a cyst on her back, it seems that she is heading for a similar fate to that suffered by Gregor Samsa, the man-turned-beetle of Kafka’s Metamorphosis. But writer-director Marielle Heller’s compelling adaptation of Rachel Yoder’s 2021 novel takes a different path, exploring modern motherhood, its complexities and its primal core.

Adams is superb as the unnamed woman, an artist who has found herself drained of all autonomy, stuck in a mind-numbing routine and approaching full-blown breakdown. She adores her toddler son (played by twins Arleigh Patrick and Emmett James Snowden), but wishes that her horizons had not narrowed so drastically. Her husband (Scoot McNairy) is on the road working most of the time and lacks the emotional intelligence to see what is happening to her.

Soon, the local dogs are leaving kills on the stoop as tribute to Adams’s canine alter ego. This, and the fact that her husband finds her in the shower covered with mud after another nocturnal adventure, suggests that the transformations are not hallucinatory. But Heller, wisely, leaves this question open, and adds in a dash of the occult for good measure. Nightbitch is really about agency: can Adams’s character recover her artistic muse and reconcile it with the profound power of motherhood?

Book

Dorothy Parker in Hollywood, by Gail Crowther (Gallery Books)

Best-known for her poems, short stories, theatre reviews and caustic witticisms (“Take me or leave me; or, as is the usual order of things, both”; “Scratch a lover, and find a foe”; “What fresh hell is this?”), Dorothy Parker is rarely understood through the prism of her screenplays. Yet she wrote or co-wrote at least 18 movie scripts, including two for which she received Oscar nominations: David O. Selznick’s A Star Is Born (1937) and Stuart Heisler’s Smash-Up: The Story of a Woman (1947).

Gail Crowther’s fine biography shows how much a straightforward reframing can achieve: she shifts the focus from the familiar Parker of the Round Table group that met at the Algonquin Hotel on West 44th Street in Manhattan and traces instead her long career on the west coast.

Though Parker hated Hollywood – “as dull a domain as dots the globe” – she appreciated the money. Initially taken on for $300 a week by MGM, she and her second husband, Alan Campbell, were at one point pulling in about $20,000 per month – a huge sum in the 1930s.

The book is also good on the serious politics that lurked beneath Parker’s love of acidic aphorism. She travelled to Spain to support the Republic, co-founded the Anti-Nazi League and the Screen Writers Guild, and was investigated by the House Un-American Activities Committee and the FBI, branded a communist, and blacklisted. When she died in 1967, her estate was left to Martin Luther King Jr.

In a life scarred by alcoholism, depression and attempted suicide, she was haunted by the suspicion that her writing made no political mark: “ridicule may be a shield, but it is not a weapon”.

If you are in the mood for more Parker, a new collection, Constant Reader: The New Yorker Columns 1927-28 (McNally Editions), is also excellent.

Streaming

The Agency (Paramount+)

In a strong year for spy drama on streaming platforms – Black Doves (Netflix), season four of Slow Horses (Apple TV+) and The Day of the Jackal (NOW) – this adaptation of the acclaimed French series Le Bureau des Légendes, scripted by Jez and John-Henry Butterworth, more than holds its own.

Michael Fassbender is at his steely best as “Martian”, a CIA agent recalled urgently to London after six years in Addis Ababa. Station chief Bosko (Richard Gere) and head of strategy Henry Ogletree (Jeffrey Wright) are handling the potentially calamitous disappearance in Belarus of “Coyote”, an asset with deep knowledge of many covert missions who might have been turned. Bosko alone is briefed on top-secret Operation Felix, which may or may not be in jeopardy.

While in Ethiopia, Martian fell in love with Sami (Jodie Turner-Smith), a Sudanese academic and activist. Why, after his abrupt departure, has she turned up in London? He tries to separate his personal and professional life but is reproached by Henry: “It’s the agency! Nothing is personal!”

Meanwhile, he is trying to rebuild his relationship with his teen daughter, Poppy (India Fowler), who is distinctly unimpressed by his long absence from her life. Martian is also tasked with training rookie agent, Danny (Saura Lightfoot-Leon), preparing for her first mission, undercover in Iran.

The Agency is conventionally sleek, in contrast to the entertaining tawdriness of Slow Horses and the comedy of Black Doves. But as an exploration of the near-psychosis at the heart of all espionage, it works very well.