September 5 (general release)

“It’s not about politics, it’s about emotion”: in this off-the-cuff remark about sporting contests between the US and Cuba does legendary newsman Roone Arledge (Peter Sarsgaard) set the scene for Tim Fehlbaum’s compelling account of the terrorist massacre at the 1972 Munich Olympics; and, more specifically, how ABC TV reported the crisis.

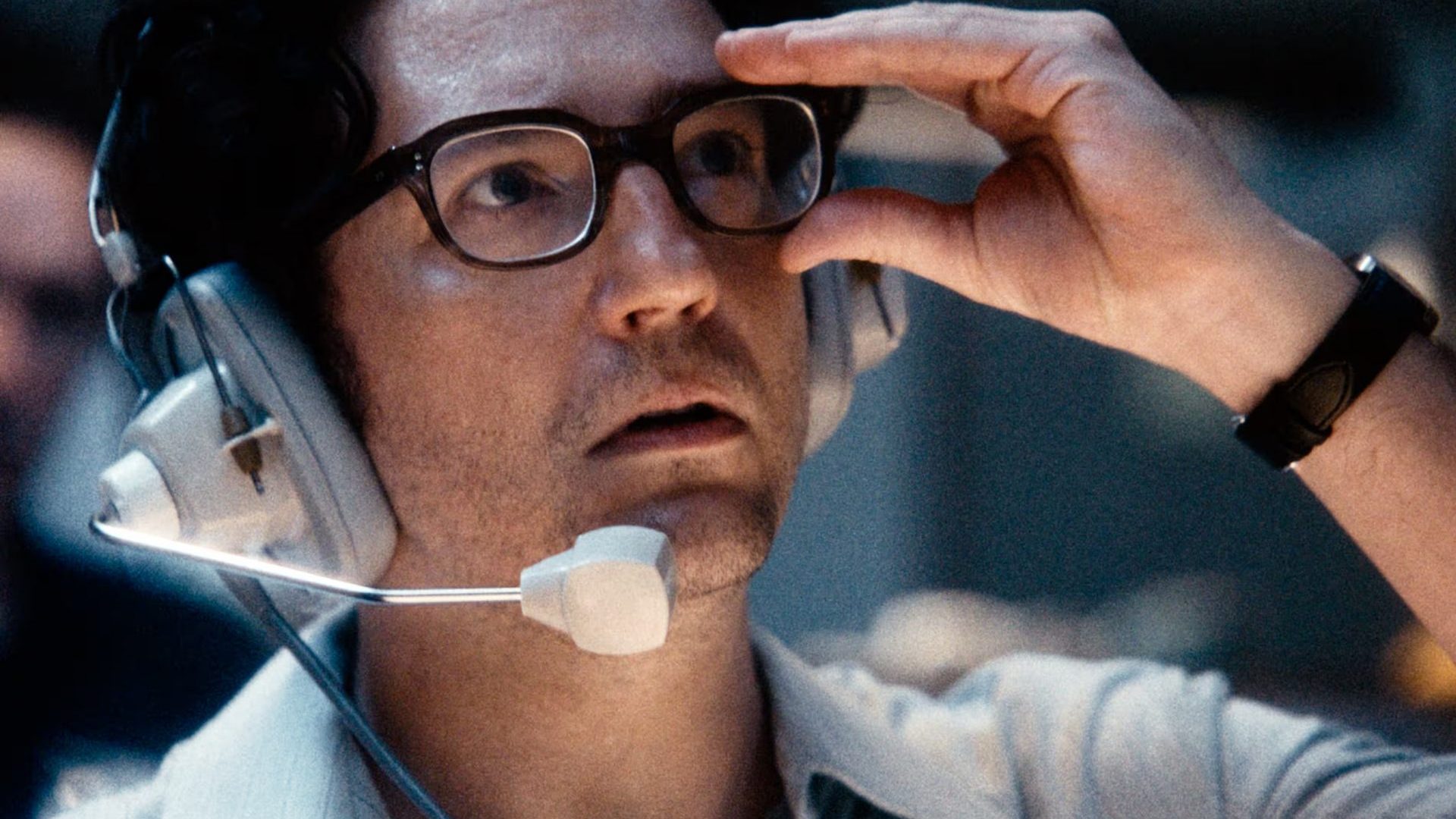

John Magaro is excellent as Geoffrey Mason, the young producer left in charge of the control room overnight, who suddenly finds himself covering the biggest story in the world. After he and his colleagues hear shots fired in the Olympic Village, it emerges that the Palestinian terrorist group Black September has killed two Israelis and taken nine others hostage.

Peter Jennings (Benjamin Walker), a star reporter with deep experience of the Middle East, gets close to the apartment block where the crisis is unfolding, huddling on a balcony. As security tightens, Mason smuggles 16mm film reels back and forth from his location by dressing a crew member as a Team USA athlete.

Arledge hits the phones and trades satellite time with CBS. He also resists his bosses’ demands to yield control of the story: “We’re not giving this story to News… Sports is keeping it”. His stubbornness is consequential because the ensuing coverage uses all the techniques of sports reporting – and its emphasis upon spectacle.

As the hours pass, it dawns on Mason that ABC is not just reporting the story but – because the terrorists can see how the crisis is being covered on-screen – participating in it. “Can we show someone being shot on live television?” he asks. Nobody has an answer to the question, because it has never confronted a major news network.

Any film director tackling this story afresh must acknowledge the long shadow of Kevin Macdonald’s Oscar-winning 1999 documentary One Day In September and, to a lesser extent, Steven Spielberg’s Munich (2005). But Fehlbaum’s subject is not the hostage crisis itself but the journalistic milestone of its coverage. The movie communicates the flop sweat of a claustrophobic studio, of DIY methods employed at speed in the analogue age, of making do under extraordinary pressure with walkie-talkies and hand-made logos.

September 5 has been criticised for failing to engage with the broader context of the Middle East conflict, then and now. But the whole point of the movie is that the geopolitical significance of the crisis trembles at the nervous edges of the screen, as the newsmen remorselessly pursue the story, and the story alone.

A German translator, Marianne Gebhardt (Leonie Benesch), fears that the horrors unfolding in the village will become yet another charge levelled against her nation. Senior producer Marvin Bader (Ben Chaplin), who is the son of Holocaust survivors, growls about the complicity of her parents’ generation in wartime atrocities. But these are asides in an otherwise tightly focused drama.

ABC would go on to scoop up 29 Emmys for coverage that was watched by 900 million people. The reporting of crises in real time was transformed forever – as big a change in media culture as was brought about by the US party convention debates between Gore Vidal and William F Buckley Jr in 1968 (also on ABC). What September 5 conveys with impressive subtlety is the repressed unethical unease that lurked beneath the spirit of newsroom triumph.

Oedipus (The Old Vic, London, until March 29)

You wait ages for one Oedipus, then two come along at the same time. Hot on the heels of Robert Icke’s production starring Mark Strong as the king of Thebes and Lesley Manville as his queen, Jocasta, comes another striking version, with Rami Malek and Indira Varma in the lead roles.

Co-directed by Matthew Warchus and Hofesh Shechter, Ella Hickson’s new adaptation of Sophocles’ text is rendered as a primeval fable of power, climate disaster and humanity’s restless search for knowledge. Malek’s other-worldliness embodies the play’s nervous thematic core, which is that the drought afflicting the ancient city is related to a terrible secret. Varma is a more rational figure, urging him not to seek answers so compulsively – least of all from the seer Tiresias (Cecilia Noble). Nicholas Khan as Creon, the theocratic pretender, is also very good.

As I wrote last month of Elektra (the other big Sophocles production in the West End, at the Duke of York’s Theatre until April 12), myth translates best to stage when it is elemental, primal and dynamic. The most dazzling feature of this production is the choreography: Schechter deploys his dancers as a chorus in motion, intervening in the drama with power and precision. Along with Tom Visser’s remarkable lighting, these moments entrench the sense of divine fury and a relentless path towards a terrible fate.

Paradise (Disney+)

A populist US president who bows to the wishes of a ruthless tech oligarch: stretches credulity, no? Dan Fogelman cannot possibly have foreseen the ascendancy of Elon Musk when he was creating this excellent eight-episode drama, but the resonance is uncanny.

In his bathrobe and with a glass of the hard stuff in hand, President Cal Bradford (James Marsden) appears content to defer to Julianne Nicholson’s Samantha Redmond – codenamed “Sinatra” because she is boss of the rat pack. He doesn’t know where Syria is on the map, which is also pretty close to the bone. “People seem to like me,” he says, as if that makes up for everything else.

Since the trailers included this plot point, it is hardly a spoiler to say that, in episode one, Bradford is found dead in the presidential residence by his lead Secret Service agent Xavier Collins (Sterling K Brown, terrific).

Collins is a widower raising two children, and, it is clear, has distinctly mixed emotions about the murdered commander-in-chief – for whom he previously took a bullet. He is also increasingly concerned by the behaviour of his subordinate and friend, Billy Pace (Jon Beavers), whose back-story is quite something.

There is a humongous reveal at the end of episode one, which I certainly will not spoil: suffice to say that it will transform the way you see the whole show; and, to my mind, makes Paradise all the more enjoyable.

Day of the Fight (Icon Film Channel now; selected cinemas March 7)

In the canon of boxing movies, a special place is reserved for Stanley Kubrick’s 1951 documentary short about middleweight Walter Cartier, from which Jack Huston’s excellent directorial debut borrows its title. As the grandson of the great John Huston – whose Fat City (1972) is also a magnificent fight flick – he also has big dynastic shoes to fill. But he accomplishes the task with grace and confidence.

Michael Pitt is excellent as “Irish” Mike Flannigan, a former champion whose manager Stevie (Ron Perlman) has blagged him a spot on an undercard at Madison Square Garden. On the day of the bout – some time in 1989 – he visits all the significant people in his life: his best friend Patrick, now a priest (John Magaro again); his uncle (Steve Buscemi); his ex-wife Jessica (Nicolette Robinson); and his father Tony, stricken by a stroke, and, in a knowing wink to Raging Bull (1980), played by Joe Pesci.

Peter Simonite’s fine black-and-white cinematography also nods to the Scorsese classic and gives aesthetic force to the theme of a man looking back on a profoundly troubled past. “I don’t deserve to live,” says Mike. “Not with what I done.”

The trope of the haunted pugilist seeking redemption with one last fight is a familiar one. But this is an exquisitely realised genre piece.

Source Code: My Beginnings, by Bill Gates (Allen Lane)

As so many tech titans sell their souls to the Dark Side, it is a good moment to be reminded that not all digital pioneers are Lords of the Sith. Step forward Bill Gates, founder of Microsoft and renowned philanthropist, with this first volume of a planned trilogy of memoirs.

The author, who turns 70 in October, offers an origin story that is refreshingly candid about the privileges of his upbringing in Seattle, Washington – not least his very early access to a computer at school in 1968, when he was only 13. He would go on to found Micro-Soft (as it was originally known), with a fellow pupil, the late Paul Allen.

Aged 15, the techno-prodigy was writing payroll programmes for local companies. “I loved how the computer forced me to think. It was completely unforgiving in the face of mental sloppiness,” he recalls. “It demanded that I be logically consistent and pay attention to details”. At Harvard, he gained access to the university’s Aiken computation lab and fell in love with its DEC PDP-10 mainframe.

There is considerable self-awareness in these pages. Once Gates had discovered his youthful aptitude for maths, he became “an argumentative, intellectually forceful, and sometimes not very nice adult”. The formal discipline of coding “appealed to my sense of order” – as well as a ferocious competitiveness that made him want to be first and best in this fledgling revolution, “to win every game I played” and to inhabit a “zone of total focus”. He speculates that if “I were growing up today, I probably would be diagnosed on the autism spectrum.”

Gates was once the very incarnation of tech disruption and radicalism. Today, his dedication to the Enlightenment values of science and conviction that “the world can be understood” feel appealingly old-fashioned compared to the monomania of the generation that followed him.