Blitz (Selected London cinemas now; general release November 8, Apple TV+ November 22)

Steve McQueen’s historical drama is the best film yet made about Hitler’s bombing of London – better even than John Boorman’s Hope and Glory (1987).

As fire rains down on the capital, munitions factory worker Rita (Saoirse Ronan) takes the agonising decision to put her nine-year-old son George (Elliott Heffernan) aboard an evacuation train. She is left, suffused with guilt, living in Stepney with her father Gerald (Paul Weller) – George’s father, Marcus (CJ Beckford), a Grenadian immigrant, having been unjustly deported years before.

Early in the journey, George leaps from the train and begins the long trudge back to London. What follows is the wandering of a child through a world turned upside down by conflict.

Blitz has been criticised as a film constrained by narrative and thematic convention, but the opposite is true: with his characteristic eclecticism, McQueen quarries The Railway Children, Dickens, Man Ray, music hall, Hogarth and the oratory of Linton Kwesi Johnson to plot George’s trek through a city full of love and of its opposite.

At one stage he is helped by a friendly Nigerian air raid warden named Ife (Benjamin Clémentine) – based on a real person who delivered a passionate speech (dramatised here) in a shelter about the need for London’s communities to unite against the racism of the Nazis. Rita offers to help Mickey Davies (Leigh Gill), another real-life figure who used the basement tunnels of the Spitalfields Fruit & Wool Exchange as a shelter for 5,000 Londoners and helped to inspire the NHS.

But there is moral ugliness too. George is lured by the promise of a sandwich to work for a gang of thieves led by Albert (Stephen Graham) and Beryl (Kathy Burke). They steal jewellery from dead bodies at the wreckage of the Café de Paris – after one of the most powerful sequences in the movie, in which the revellers at the grand nightclub dance deliriously to Celeste singing “Oh Johnny, Oh Johnny, Oh!”, until they hear the lethal descent of a high-explosive bomb.

McQueen does not conceal the carnage, chaos and brutality of the Blitz: the opening image, a fire hose turning like a violent serpent on the men trying to control it, signals the presence of the monstrous. And he reminds us of the harsh historical fact that Londoners were initially barred from seeking sanctuary in the Underground. As McQueen said at the preview I attended, “life is much more complex” than historic folklore would suggest.

The music by Hans Zimmer and Nicholas Britell is superb, as are the smoke-covered hellscapes designed by Adam Stockhausen. Both textured and monumental, Blitz is the work of a great British director at the height of his powers.

Francis Bacon: Human Presence (National Portrait Gallery, London, until January 19)

Two years after the Royal Academy’s stunning exploration of the relationship between man and the animal kingdom in Francis Bacon’s work, the NPG mounts the first major exhibition of his portraits for almost two decades. The focus is instructive, revealing as it does the brutal tension between his affection for friends and lovers and the pitiless grotesquerie of his aesthetic vision.

For this reason, he preferred his subjects not to sit for him, not wishing “to practise before them the injury that I do to them in my work. I would rather practise the injury in private”. Instead, he usually painted from memory or from photographs taken by his friend John Deakin.

Given his distaste for mere “illustration”, it is no surprise that Bacon’s notion of portraiture was unrestrained by conformity or protocol of any kind. In 1951, Lucian Freud was surprised to see that his supposed likeness had, in fact, been taken from a picture of Kafka. Bacon often painted a hybrid of his own and his subject’s features, as if the very act of portrait-painting was a form of possession.

Yet the tenderness that he felt towards lovers such as Peter Lacy and George Dyer and friends like Freud, Henrietta Moraes, Isabel Rawsthorne and Colony Room founder Muriel Belcher always hovers bashfully alongside the visual violence. Triptych May-June 1973, which depicts Dyer’s suicide in 1971, is perhaps the most powerful and heart-rending of the works on display.

“I couldn’t [paint] people I didn’t know very well,” Bacon said. It is perhaps no surprise that the subject upon whom he visited most cruelty in his portraits was himself.

Heretic (General release)

Two Mormon missionaries, Sister Barnes (Sophie Thatcher) and Sister Paxton (Chloe East) are invited to the secluded home of Mr Reed (Hugh Grant) to talk about their faith. Though a little skittish, he is charming and apparently eager to hear their pitch – promising them blueberry pie and, as soon as possible, the presence of his wife (the rules of their evangelism require another woman to be in the room when they are passing on their divine message to a man).

Writer-director duo Scott Beck and Bryan Woods have fun with the audience as it becomes clear that Mr Reed is not a bumbling Englishman at all but a deeply sinister recluse who intends to subject the two missionaries to a gruelling theological test. Should they go through the door marked “Belief” or “Disbelief”? What use are the teachings of Joseph Smith and the Latter Day Saints to them now? And what exactly is in the basement?

Grant has never been better or darker, riffing gleefully on the media’s perception that he has been a wrong ’un all along, and East and Thatcher ensure that his character is also tested till the very last scene. I especially liked the way in which the apparently ordinary house slowly mutated into a true labyrinth of horror. A superior fright flick, ideal for Halloween weekend.

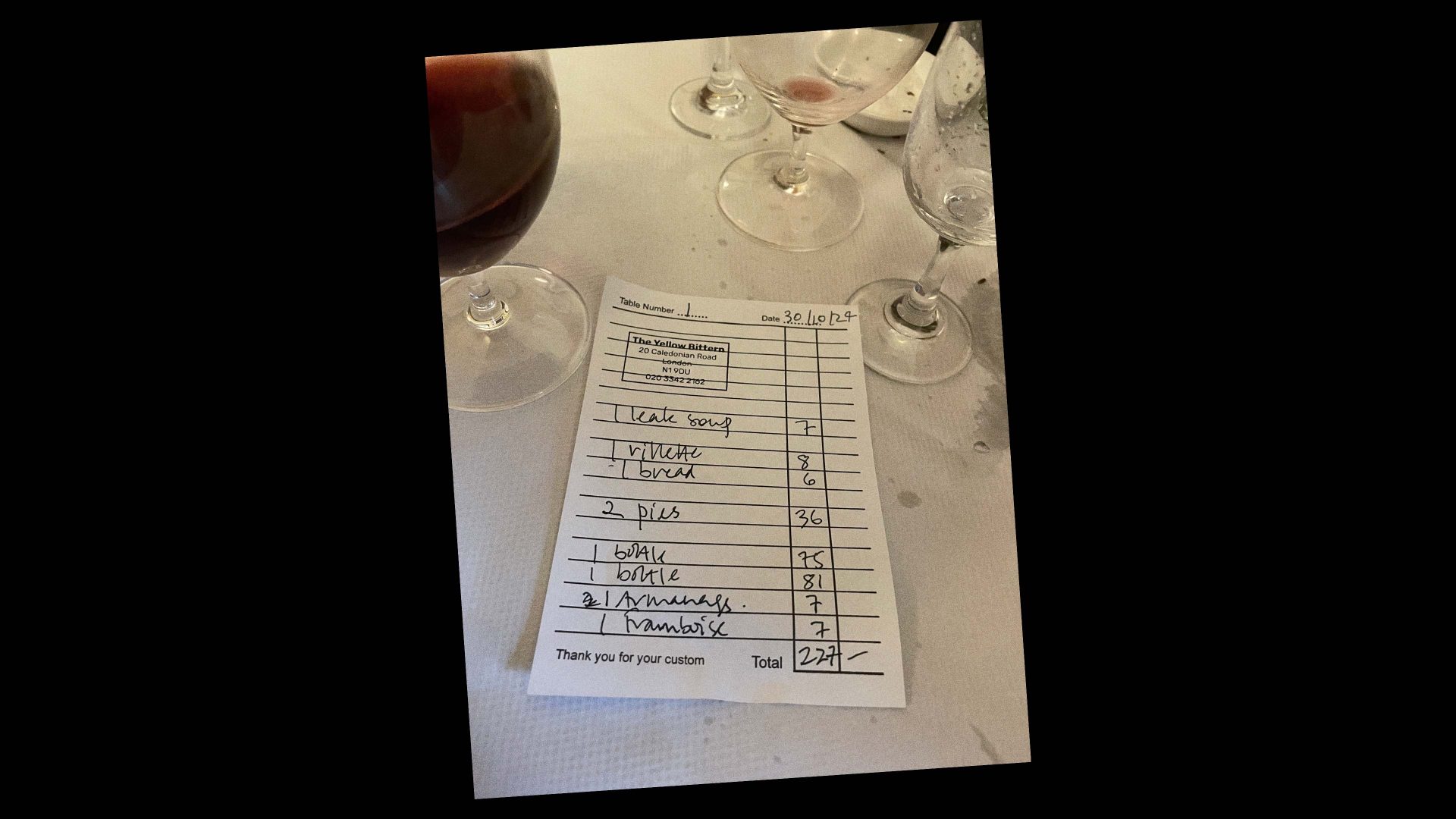

The Use of Photography, by Annie Ernaux & Marc Marie (Fitzcarraldo Editions)

Though its title suggests a debt to Susan Sontag’s classic 1977 collection of essays on photography, this exquisite book – originally published in France in 2005 and now translated by Alison L. Strayer – is the account of a passionate love affair overshadowed by the prospect of death.

In a Rive Gauche restaurant in January 2003, the writer Ernaux has dinner with the photographer and journalist Marie, and they become romantically entangled. Though Ernaux went on to win the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2022, the year of Marie’s death, it was she who, at the time, was contemplating the end of her life as she was then being treated for breast cancer.

Even as she fell for Marie, she faced “the obvious fact that for others I had become someone else. I could see my future absence in their eyes”. Battered by her visits to the Institut Curie, “my body was a theatre of violent operations”.

The story of their affair is punctuated by 14 photographs, erotic only in the sense that they convey the urgency with which clothes and shoes have been shed and tables left uncleared. As Ernaux writes, she wanted to record “this arrangement born of desire and accident” before it was tidied and forgotten.

Worth noting that, as always with Fitzcarraldo, the book itself is an object of understated beauty.

Curfew (Paramount+)

Imagine a Britain in which all male citizens over 10 are electronically tagged and confined to their homes between 7pm and 7am. Adapted from Jayne Cowie’s book After Dark (2022) and directed by Joasia Goldyn, this six-part crime drama stars the always excellent Sarah Parish as DI Pamela Green – whose daughter was murdered only 48 hours before the Women’s Safety Act came into effect.

When a woman is killed during curfew hours, her body provocatively dumped outside the Women’s Safety Centre, DI Green is convinced that the crime was committed by a man: a hunch that goes down badly with her superiors, who are under political pressure to demonstrate that the new measures have ended male violence towards women.

The imagined detail is well-observed: classroom arguments about the fairness of the curfew; couples requiring counselling before they are given “cohabitation certificates”; and a misogynistic activist group calling itself “Alpha”, led by the mysterious Andrew Tate-style “Duke”. Green’s new partner Eddie (Mitchell Robertson) needs a special exemption to work after 7pm.

Along the way, there are plenty of twists and red herrings to ensure that the identity of the killer is far from predictable. Having created this intense, fractious and plausible world of speculative fiction, I hope the makers of Curfew are granted a second season in which to explore it further.