It has become commonplace, you may have noticed, to argue that the traditional left-right division of politics has been supplanted by a contest between “open” and “closed” systems, societies and cultures: an analytic approach championed in particular by Tony Blair.

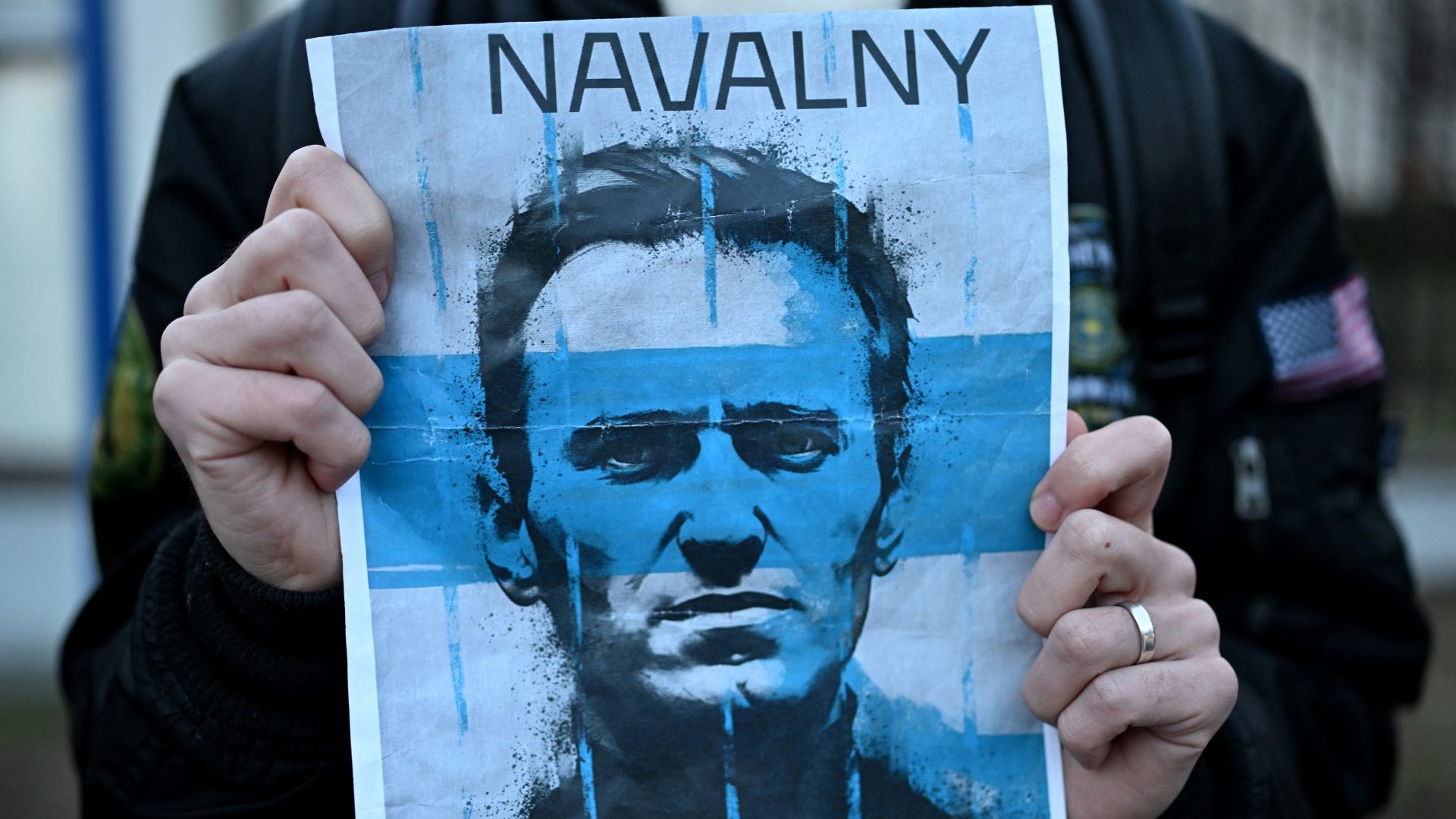

Yet since the death of Alexei Navalny at the IK-3 high-security Polar Wolf prison in the Arctic Circle on Friday, it has occurred to me that there is a parallel conflict between two very different varieties of “openness”: one championed by the late Russian dissident, and the other by Vladimir Putin, the autocrat who was unquestionably responsible for his murder – in a single act of assassination last week or a campaign of relentless persecution.

Navalny, who was only 47 when he died, personified a hypermodern version of political transparency and online glasnost. In his crusade against corruption, cronyism and venality, he made ingenious use of viral YouTube videos and other digital tools to embarrass his opponents, flying drones over their palatial homes built with embezzled money, firing off memes to puncture their self-importance.

He launched a “Smart Voting” app to help Russian citizens identify candidates with the best chance of beating opponents aligned with Putin (an app that Apple and Google cravenly removed from their stores in September 2021, under pressure from the Kremlin). His natural charisma, ready wit and gift for mimicry were perfectly suited to the new platforms available to his generation of politicians. He understood the capacity of loose-knit networks to challenge old-fashioned institutions.

In defending the rule of law and natural justice, he turned to state-of-the-art open-source methods of investigation. When the FSB poisoned him with a novichok nerve agent in August 2020 – very nearly killing him – he collaborated with the high-tech journalism group Bellingcat to track down the unit responsible.

In Daniel Roher’s Oscar-winning documentary, Navalny, we see him on the phone pretending to be a senior member of Putin’s apparat and deftly coaxing a confession from one of the conspirators. The scene is as hilarious as it is chilling. It dramatises both the brutal lengths to which the repressive Russian state is willing to go to silence its critics; and the emancipating power of mockery.

The second version of 21st-century openness is the brazen, utterly shameless character of the autocracy practised by Putin and his fellow strongman leaders. As Andrei Soldatov and Irina Borogan, authors of The New Nobility and The Red Web, have shown in their studies of the modern Russian security apparatus, intimidation, menace and the cultivation of unease are much more important now than the maintenance of absolute secrecy or traditional tradecraft. Indeed, the flagrancy is the point. Peter Pomerantsev, author of the masterly Nothing Is True and Everything Is Possible (2014), has put it well: “This has always been [Putin’s] final argument: that he can carry out any crimes at home, any invasion abroad, any war crime from Grozny to Aleppo, and get away with it”.

This was why he used Novichok in the assassination attempt of 2020; it was the same nerve agent with which his agents had tried to kill the defector Sergei Skripal and his daughter Yulia in Salisbury in 2018. It also recalled the lethal poisoning of the former KGB officer Alexander Litvinenko with tea laced with radioactive polonium in London in 2006.

This was, to use a term much loved by John le Carré, Putin’s “handwriting”: an explicit calling card to his enemies. It was also why Navalny’s predecessor as effective leader of the opposition, Boris Nemtsov, was shot dead en plein air near the Kremlin in 2015, while walking home with his girlfriend. As Navalny himself conceded: “Murder is a terrific way to solve problems”.

Increasingly, Putin has scarcely bothered to disguise the barbaric nature of his rule. Challenged at a press conference in December 2020 to account for Navalny’s brush with death, he made light of the whole thing: “If that was the intent, they would have finished him off”. When Yevgeny Prigozhin, leader of the mercenary Wagner Group, launched a coup in June but lost his nerve, he sealed his fate – killed in a plane crash in August that was almost certainly the result of sabotage.

Yet Navalny succeeded in getting under Putin’s skin: he could not bear to utter his name in public. Terror and impunity have long been the Russian president’s greatest allies; and the young pretender challenged both. In his nimble, demotic attacks upon the autocrat and his allies, in his baiting of the seething bear and, above all, in the sheer physical courage he displayed by returning to Russia in January 2021 – facing certain arrest and probable death – Navalny defied the whole basis of the regime.

He had hoped to be Russia’s Mandela, imprisoned and then released to lead his nation to a brighter future. But Putin was not going to allow that. It seems no coincidence that Navalny died on the eve of presidential elections (if they are worthy of the name); during the Munich Security Conference (at which the dissident’s wife, Yulia, spoke movingly); and eight days before the second anniversary of his illegal invasion of Ukraine.

As ever, Putin’s message was simple. To the people of Russia: these are the wages of opposition. And to the rest of the world: what are you going to do about it? Here is a tyrant who does not expect to be held truly accountable; instead, he has grown used to intermittent scolding, sanctions that can be circumvented, and a strategy of broad appeasement masquerading as strategic containment.

Joe Biden says he is busily “contemplating” the US response to this outrage. David Cameron, the UK’s foreign secretary, has declared that there ought to be “consequences”. The G7 has issued what was presumably intended to be a scary statement calling on Russia “to stop its unacceptable persecution of political dissent”.

On Sunday, the US and UK ambassadors to Moscow laid floral tributes to Navalny at the Solovetsky Stone on Lubyanka Square. There will be more speeches, calls for investigations, and some token measures by the international community. But there will be no genuine gear-change.

Look: I hope I am wrong. I would love to see the military pressure on Russia intensify radically, economic penalties multiply, diplomats expelled en masse, Ukraine fast-tracked into Nato. But I detect a worrying decadence in the west’s response to Navalny’s death specifically, and to Putin’s conduct generally; a prevalence of performative rhetoric over meaningful action.

On the left, one could already sense this in Jeremy Corbyn’s risible suggestion that a sample of the nerve agent used to poison the Skripals be sent to the Kremlin to establish whether it was indeed of Russian origin. Disgracefully, Navalny was stripped of his “prisoner of conscience” status by Amnesty International in 2021 because of some foolish xenophobic statements he had made early in his political career and later renounced. True enough, he was no saint. But how many dissidents are?

The fall of apartheid depended upon relentless international campaigning, and a powerful collective belief in fundamental civil rights. But the social and political context has changed dramatically since Mandela walked free from Victor Verster Prison in February 1990.

In the 1960s, students at Berkeley marched for free speech under the leadership of the great Mario Savio. Today, they march to curtail it and to “deplatform” those whose opinions they dislike. It is hard to imagine them being as moved as their predecessors were by the plight of Andrei Sakharov, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn or Vaclav Havel.

For all his political glamour and the righteousness of his cause, Navalny did not fit neatly into any of the rigid categories beloved of the modern social justice movements. Yes, there have been vigils and demonstrations in his memory, both within and outside Russia. But you can be sure that hundreds of thousands will not take to the streets of western cities chanting his name, demanding justice.

Even worse is the response of the right, especially in America. How the Russian leader must have relished the refusal of Republicans to authorise the latest $60bn tranche of military aid to Ukraine. Six days before Navalny’s death, Donald Trump, who did nothing when Navalny was poisoned in 2020, disgraced himself further by encouraging Russia “to do whatever the hell they want” to Nato members that do not pay their fair share to the alliance.

After his feeble two-hour interview with Putin on February 6, Tucker Carlson was taken to task over his failure to confront him about his repressive methods. “Every leader kills people,” he replied. “Leadership requires killing people, sorry”.

Worst of all, Trump’s supporters have tried to establish a moral equivalence between Navalny’s murder and the 91 felony charges against the former US president. On Friday, the right wing political commentator Dinesh D’Souza wrote this dismal post on X: “Navalny=Trump. The plan of the Biden regime and the Democrats is to ensure their leading political opponent dies in prison. There’s no real difference between the two cases”.

Such lazy contempt for facts and decency, on the day that a brave man died in the frozen wastes of Siberia, is a terrible reflection of how far political culture has sunk in the free world. This moment is, as Litvinenko’s widow, Marina, said on Friday’s Newsnight, “a huge challenge for the west”. In The Gulag Archipelago, Solzhenitsyn wrote: “Every man always has handy a dozen glib little reasons why he is right not to sacrifice himself”. Navalny offered no such excuses and paid the ultimate price in the modern gulag. His sacrifice is a reproach to a dithering world. But it could yet be an inspiration.