When he died in October 2013, Kadir Nurman received an obituary in the Times. That was then, as now, not an honour afforded to most Turkish-born operators of West Berlin snack-food stands. But then Nurman – probably, possibly – occupies a unique role in fast-food history: the man who invented the doner kebab.

The story goes that Nurman, who moved from Anatolia to West Germany as a Gastarbeiter, or “guest worker”, in 1960, was the first person to hit upon the idea of taking kebab meat – cooked on a vertical grill and carved from the skewer since the days of the Ottoman empire – and, rather than serve it indoors on a plate alongside generous portions of rice, to put it in bread. Nurman had spotted that the salarymen who passed the Zoologischer Garten S-Bahn and mainline station no longer had the time for the more leisurely lunches enjoyed in his homeland. Why not render it as mobile as the ubiquitous Bratwurst served everywhere else?

That’s the semi-official history of the doner kebab, and one recognised by the Association of Turkish Doner Manufacturers in 2011. It’s also the one that saw ridicule heaped on the then junior trade minister Greg Hands in 2017 when he spotted a branch of the nascent fast-food chain German Doner Kebab, then with just 12 branches, took a picture and tweeted “How long before we have German Fish & Chips?”. Fellow Twitter users were quick to offer him a history lesson.

German Doner Kebab now has considerably north of 12 branches. But more of that later. The question is: could Kadir Nurman really have been the first person to think of putting that meat in bread?

“Not at all,” says Pierre Raffard, a lecturer in geography and geopolitics at ILERI, an international relations school in Paris. He’s considered an expert on the doner kebab (“I’m THE expert. I’m the only one,” he corrects me when we speak via Zoom). And he is not sold on the legend.

“That’s one of the most famous legends about the origin of the doner kebab,” he says.

“As a historian, it’s not right at all. I mean, we have some proof, we have some evidence of the mid-18th century in the Ottoman cities – Constantinople, for example, where the doner kebab could be found in the streets of these cities. So the origin of the doner kebab is much older than the legend.”

Nurman, he says, “invented one version of the doner kebab, but there are many versions. But the origins of the sandwich can be found in the Ottoman cities around 1850. I mean, the first available pictures of street vendors selling a meal looking like doner kebab can be found in 1854. But then the meal, the sandwich, moved to Europe at the end of the 19th century, but especially from the 1930s.”

One problem, he says, is giving a precise definition of the doner kebab.

“It’s like pizza, he says. “If I ask you ‘what is a pizza?’ you may say it’s a round base on which you will add some ingredients. The precise definition is very hard to find. It’s exactly the same thing with the doner kebab. I mean, we could describe it as roasted meat cooked on a skewer or on a spit, which is sliced in a very thin way and then served in a bread and with garniture. But after this very global and general definition you can find a lot of different versions of the meal. The kebab is more a gastronomy concept than a precise recipe. I mean, if you ask me the recipe of, I don’t know, the beef bourguignon or something like that I can really give you a precise recipe. For the doner kebab it’s much more difficult.”

When I speak to Ibrahim Dogus, the founder of the Kebab Alliance, a group that lobbies on behalf of the UK’s more than 20,000 kebab restaurants, he is more specific in his definition but equally unsure in its precise origin. (Incidentally, the alliance’s website points out that “Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II has a choice of four kebab outlets within walking distance of her home at Windsor Castle”, although it is unclear whether she has visited any.)

“The doner kebab is the rotational meat that rotates in front of a fire, whether it’s fired by gas or electricity,” Dogus, also a Labour councillor, tells me as we sit in his restaurant on the South Bank in London.

“That’s what we describe as the doner kebab, or gyro in Greek terminology. We know the story from West Berlin – we do go along with that, but there are others who will say this has been in existence for hundreds of years, we’ve seen some pictures from 1400, 1500 in Istanbul, meat on a stick, looks like a doner kebab, maybe that’s what it was, maybe that’s where it started. But people were not naming it or calling it the doner kebab at the time.”

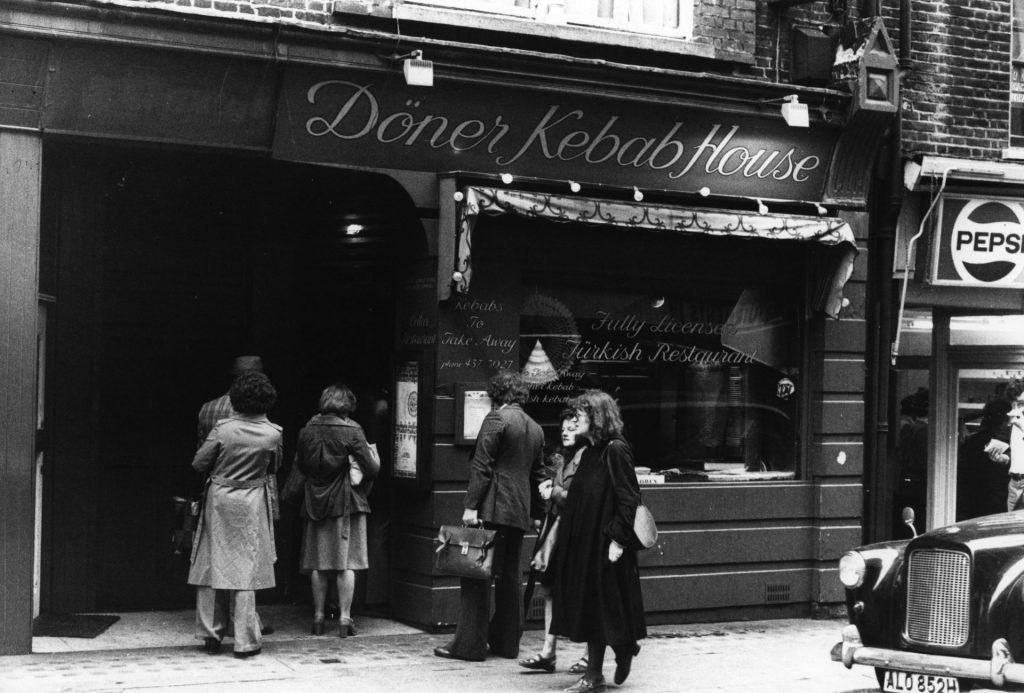

The kebab’s history in the UK is at least clearer. Its first Turkish restaurant is thought to have been Istanbul, which was opened in Frith Street, London, by a Turkish Cypriot in 1940. The first place selling what we would now recognise as doner meat, cooked on a vertical spit, is thought to have opened in Newington Green, north London, in 1966, although it is likely this was eat-in – no bread jacket required.

The huge growth in the popularity of the kebab in the UK, though, came in 1995 – but more for socio-economic reasons than the fact it coincided with the beery days of Britpop and the so-called ladette.

“That’s when the textile industry collapsed,” explains Dogus.

“And many people of Kurdish origin from Turkey, who were working long hours in those textile factories [in the UK], they had saved some money but had no idea what to do. They were not able to speak the language yet, so they could not apply for jobs. They were looking for another way to earn a living. So the first thing they did, because they cooked at home and knew how to cook these meals, they set up small restaurants in Hackney and Stoke Newington. That’s where it started.”

The initial customers, he says, were fellow Kurds and Turks. “But gradually they started seeing more people walking through their doors. And now we’ve got an industry of 20,000-plus restaurants across the country employing more than 200,000 people, generating around £3bn.”

In the UK the kebab has long been associated with what even Daniel Bunce, global chief operating officer of German Doner Kebab, describes when I speak to him later as “10 pints of lager and a kebab at two o’clock in the morning”. But it’s never taken on a political angle, unlike in mainland Europe where it can be, as in Germany, embraced as a symbol of successful cultural integration, or elsewhere seen as an example of creeping Islamisation. Perhaps it’s because we’ve had our own dishes to politicise – when, in 2001, the then foreign secretary Robin Cook described chicken tikka masala as Britain’s national dish “because it is a perfect illustration of the way Britain absorbs and adapts external influences”, he was attacked by the Daily Mail for “historical gobbledegook”.

In 2015 the far-right mayor of the southern French town of Béziers declared war on the kebab, saying he would not permit any new restaurants to be opened. After receiving criticism on social media Robert Ménard said: “I will not let Béziers become a kebab capital” (kebabs then amounted to 5% of the food trade in the region), and added that kebabs were not a part of French culture.

It is part of the reason Dogus wants to extend the Kebab Alliance’s work into France. “My next project after the British Kebab Awards [which launched in 2013] is to start up something similar in France,” he says. “British politicians are quite open-minded. And the British media is also quite open-minded. They look into the contributions these communities are making in a very positive way. But the anti-immigrant sentiments are quite strong in the French media.”

But not only in France have populist politicians sought to weaponise the kebab. In Moscow in 2016 there was an attempt to outlaw kebab stands, accusing them of failing to comply with hygiene standards. “We are ridding the streets of all shawarma. It’s going to disappear completely,” city official Alexey Nemeryuk told Russian radio station Komsomolskaya Pravda, only for #ShaurmaZhivi – “long live shawarma” or “shawarma will survive” – to trend on Twitter.

And in 2011 Forte dei Marmi, a leafy beachfront retreat on the Tuscan coast in Italy, introduced a ban on the opening of kebab shops, although it was part of a wider fight against foreign food. The mayor, Umberto Buratti, saying it wasn’t “an act of xenophobia”, added: “We would say ‘no’ to everybody, including American hamburger chains.” Raffard, though, says: “Kebabs can sometimes be considered the gastronomic black sheep or the culinary black sheep.”

Sometimes, though, the kebab is held up as a proud symbol of multiculturalism. Raffard points out it is a common trope in French rap music: “The kebab is a symbol of the hard dimension of living in ghettos. It’s a very important political, symbolic or even identity reference for the rap singers.”

And indeed, one of the biggest hits in France in 2007 came from Turkish immigrant Lil’Maaz and his hit anthem Mange du Kebab (Eat Kebab), although even this was problematic for some – the Welsh academic Jonathan Ervine wrote a paper entitled Lil’Maaz’s Mange du Kebab: challenging cliches or serving up an immigrant stereotype for mass consumption online?

Maybe in Britain attitudes to the doner are changing, too. That German Doner Kebab chain that had 12 branches when Greg Hands snapped it in 2017 has, almost overnight, become one of the fastest-growing fast-food operations in Britain, competing with McDonald’s, Domino’s Pizza and thousands of independent takeaways. First established in Berlin but based in Glasgow, it operates in Sweden, the Middle East and North America and has plans to open 400 restaurants during the next seven years.

“Although we say it’s for everyone, we do have a target demographic, which tends to be 18-30 – you obviously fit into that bracket,” says Bunce, laughing, when he joins me from Glasgow via Zoom (fun fact – I very much do not fit into that bracket).

“We brand ourselves with that urban lifestyle, sort of fast-paced feel about it,” he adds, and it’s true – when I visit a couple of their outlets in east London in the interest of research for this article, it’s seems highly unlikely the Generation Z clientele have ever downed 10 pints – the gym is a more likely post-work destination.

And the firm has its sights set well beyond these shores. Bunce speaks to me the day ahead of a new opening in Stockholm, and has “spent the best part of three or four weeks in Romania over the past three or four months”.

“I certainly think there’s more growth in eastern Europe,” he says. “We’ve been to Kazakhstan – I certainly think there’s scope out there. And the success we’ve had in Sweden has obviously encouraged us to look hard at Norway, Denmark and those northern Scandinavian countries.”

The storied march of the doner kebab, then, continues. And what of Nurman, its supposed inventor? He failed to patent his dish and later conceded that others might have hit on the idea at the same time as him.

“Maybe someone else did it too, in some obscure place, but no one made anything of it,” he said. “The doner became famous because of me.” And that, perhaps, is the closest thing to the truth.