“The European Union is going to be stronger with us. That’s for sure. Without you, Ukraine is going to be lonely, lonesome.”

Everyone’s favourite hero, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, has an actor’s skill in crafting a speech designed to appeal to a specific audience. He channelled Churchill for the Brits, name-dropped Pearl Harbor for Americans, invoked the Holocaust to Israel, and guilt-tripped the Germans.

And days after he signed an official application for his beleaguered country to join the EU, speaking to members of the European Parliament, he summoned the spirit of European unity and solidarity:

“We have proven our strength. We have proven that at a minimum, we are exactly the same as you are. So do prove that you are with us. Do prove that you will not let us go. Do prove that you indeed are Europeans.”

The proof and the promises are still lacking. At the end of February Zelensky asked for his country, already a “priority partner”, to be put on a special fast track to EU membership.

Unfortunately for him, it takes not two to tango but 27 other sovereign dance partners, all moving to different music in their heads.

Zelensky’s intense passion is in stark contrast to the measured, even complacent response from the EU to his wish to join the family. They have moved fast on sanctions and defence, but are split on speeding up the sacred membership process. Twice the EU’s prime ministers and presidents have issued a dusty statement merely noting the application and inviting the commission to “submit its opinion”.

Those countries that worry they might suffer Ukraine’s fate one day are dismayed by this deliberate sloth. Lithuania is leading a 10-strong group, called “EUkraine”, made up of mostly eastern countries demanding more haste, pointing out: “As seen from decades of EU enlargement, the prospect of EU membership is a most powerful tool for peaceful transformation and growth, as well as for anchoring the democratic freedoms and values that bind us together.”

In another highly charged speech, this time to the leaders gathered for the overlapping Brussels summits in March, Ukraine’s president name-checked all EU nations one by one:

“Lithuania stands for us. Latvia stands for us. Estonia stands for us. Poland stands for us. France – Emmanuel, I really believe that you will stand for us. Slovenia stands for us. Portugal – well, almost. The Netherlands stands for the rational, so we’ll find common ground.” And so on. But rationality is the problem in these giddy times.

Sober souls like the Dutch, Spanish, French and Germans are digging their heels in, but Ukraine’s ambition for more speed can hardly come as a surprise.

This war has some of its roots in the 2013 Maidan protests when Ukrainians revolted against the refusal of their pro-Russia president, Viktor Yanukovych, to sign an agreement setting a route to joining the EU. Instead, he opted for closer ties with Russia.

That doyen of European commissioners, Jacques Delors, once said the EU needed to find its soul. Maybe this is the moment of discovery. Of course, it is vital to keep the momentum going on real, practical help. But this is a big moment and demands big symbols. An in-your-face grand gesture, making it clear this is a struggle for what lies at the heart of the EU’s ambition. Not the deracinated bureaucracy of popular myth, but a passion for democracy, peace and freedom.

But French President Emmanuel Macron’s even-handed musings after his Versailles summit offered little hope of this.

“Can we open a membership procedure with a country at war? I don’t think so. Can we shut the door and say: ‘never’? It would be unfair. Can we forget about the balance points in that region? Let’s be cautious.”

Caution has infected the European project for years. For all its ambition for integration, it has long been tepid about granting club membership, selfconscious about its size, worried that if it puts on weight, it won’t like what it sees in the mirror.

This was on display in De Gaulle’s two “nons” to the UK, which, in a sideswipe, also delayed Denmark and Ireland. It was there when it took even prosperous and peaceful Austria six years to measure up. Even the term used, “enlargement”, is unlovely – more likely to provoke sniggers than enthusiasm.

But expansion to the east was always a special case. For decades it was simply unimaginable. While the Berlin Wall stood firm and the Soviet Union seemed unassailable, ringing words about the reunification of Europe were a safe bet, pious and aspirational, not an easily imagined reality.

In her infamous Bruges speech, Margaret Thatcher deployed the sentiment for her own ends: “We must never forget that east of the Iron Curtain, people who once enjoyed a full share of European culture, freedom and identity have been cut off from their roots. We shall always look on Warsaw, Prague and Budapest as great European cities.”

This wasn’t just the Iron Lady buckling on comfortable cold war armour, but developing the argument for another familiar fight: her contention that the European community was merely one expression of Europe, but “not the only one”.

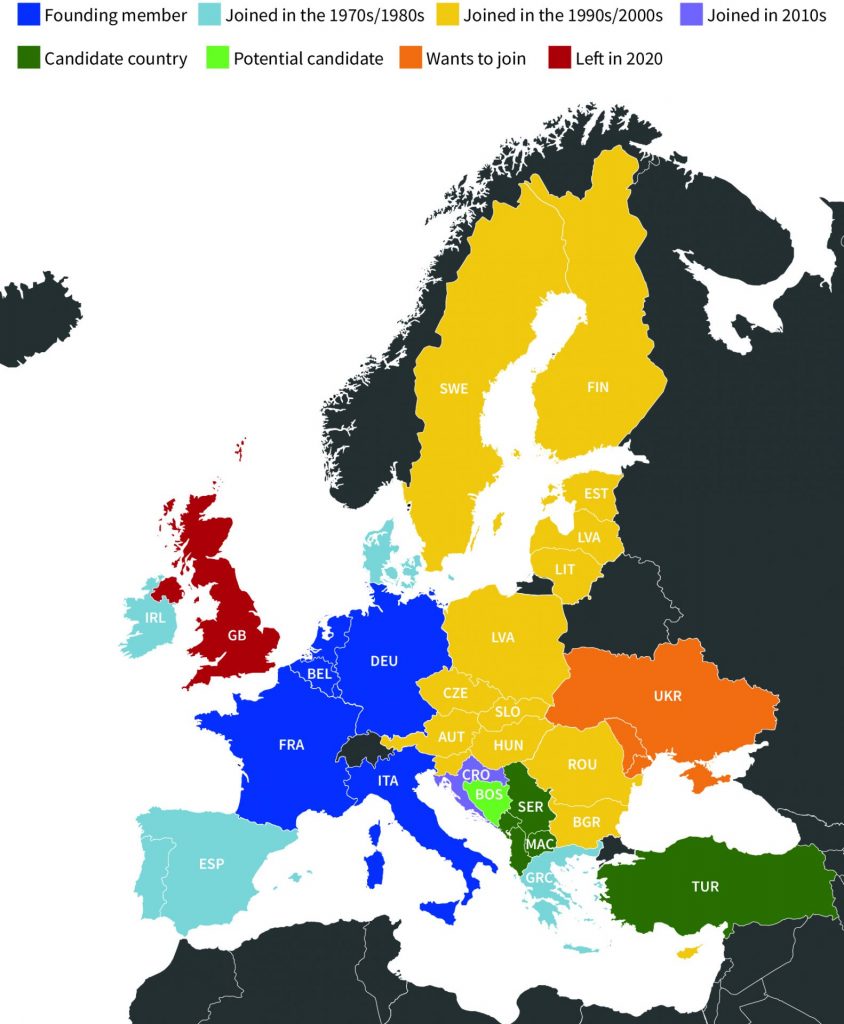

But it became the main one for those no longer marooned behind that curtain. With staggering speed after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 one former Soviet satellite joined the Western European project almost automatically. In less than 12 months East and West Germany were united. For all the agonised debate about what a resurgent Germany would mean for Europe and the world, there was also wild joy and fierce celebration of a hurt undone, two severed halves made whole once more.

As the Wall fell, Chancellor Helmut Kohl spoke movingly of it as “an inhuman barrier separating the Europe of freedom from the Europe of dictatorship, thereby also separating people – who belong together”.

By the time eight other former communist countries overcame that separation and joined the EU, 14 years had passed and it all felt rather different. Freedom was a given and high-flow rhetoric no longer came naturally. The sense of joy, the heady exhilaration at a new future, had long since dissipated, drained into practical ground littered with new rules and regulations.

To be sure, on the night of May 1 2004 there were celebrations across the continent: Poland marked the moment with a midnight military parade and fireworks, Estonia with parties on the streets, Hungary with tastefully waved flags and a classical concert.

It was indeed a big deal. For 18 long years, even as the EC morphed into the EU, it had stuck at 12 countries. Now it was to almost double in size.

There were to be 10 new members. Among them, two Mediterranean islands: Malta and Cyprus. But the bulk was made up of eight eastern countries. All ex-communist; three of them, the Baltic states, actually used to be component parts of the Soviet Union itself.

Rather amazingly, given what is happening now, even Moscow looked on with approval. Later that May, in his State of the Union address, President Vladimir Putin said “the expansion of the European Union should not just bring us closer geographically but economically and spiritually”.

This welcome didn’t last long. In the following year’s speech, he bemoaned the collapse of the Soviet Union as the “greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the century”.

For others, history had ended and ushered in an age of complacency. It had been a long and grinding road into the EU and along the way the magic got lost for both sides in a welter of detail and nerves.

By the time Poland and Hungary sent in their official letters to join in 1994 there was lots of detail about road links, agricultural prices and the rule of law, but barely a nod to the wider purpose. The minutiae of dovetailing very different economies was complex by its very nature and some were playing a cynical strategic game.

No doubt many British politicians were genuinely excited by the idea of embracing the East, not least as Nato partners and fans of the free market, but for many in the Foreign Office it was about slowing “ever deeper union”.

If Europe became wider it could not also become deeper – the more members, the less integration, the less European union. This was not entirely true to begin with – the euro was the price for German reunification – but like a python that has swallowed a goat, the European project would have to rest up for a while before it embarked on anything new, or risk a bad case of indigestion. It worked, only too well.

Along the way the aspiring countries were treated rather like potentially troublesome children who would one day be allowed into the front parlour to take tea with the grown-ups if only they could learn to wash properly and subject themselves to frequent inspections underneath fingernails and behind their ears. They put up with this for the economic advantage, but there was an absence of romance on both sides.

It was completely understandable: there was no threat of being gobbled up by a dark past, only a choice between the future and limbo. It all added to a widespread feeling that the EU was about to bite off more than it could chew, and its largesse had to stop somewhere.

The then president of the European Commission, Romano Prodi, said a couple of years before the big expansion: “We must have an open debate on where the EU’s borders are to be. Europe cannot just be a lump of jelly without definite borders.” Understandably not as far as Moscow. “I said to Putin: ‘Well, yes, you are European, even if you are looking eastwards, but you are too big for the EU’.”

Asked about other, smaller countries that see themselves as European, such as Georgia, Prodi was contemptuous: “People in New Zealand also feel that they are European. That is the problem. We cannot limit ourselves to considering the historical roots. We also have to give a natural size to the EU.”

It all added to the sense that expansion to the east was a burdensome and dangerous chore, rather than a part of the mission.

That limit to the EU’s “natural size” is only one worry. Some of those swallowed in 2004 have indeed turned out to be hard to stomach. There are those like Romania and Bulgaria whose fight against corruption has often been less than half-hearted. Even tougher to digest have been the populist and illiberal governments of Hungary and Poland, wilfully offending against basic democratic values.

Many of the new candidates, very much including Ukraine, would carry the risk of further bloating the snake to the point of bursting its skin.

As well as all the old potential problems, the current crisis brings the danger of headbutting against Putin into sharp focus.

Moldova and Georgia quickly followed Ukraine in asking for a fast track to membership, obviously fearful they would be next on Putin’s list. Lining up behind them are 10 others, including Serbia, Albania, and Kosovo, all of whom would bring with them specific concerns about Russia’s approach. Until last summer even Belarus was part of the EU’s “Eastern Partnership”.

All this underscores both Putin’s real worry and why the EU needs to find its soul in a flamboyantly generous gesture. It is clear why many countries want to shelter under Nato’s protective nuclear umbrella. That should be up to them, not Putin. But it is also obvious why Nato is hesitant about spreading its protection too far and wide. It is also too easy to portray any expansion as military aggression.

It is far harder for Putin to brandish EU membership as a threat even if it is a symbol of what really keeps him awake at night. Another flourishing successful democracy on his doorstep. Not a nation that has “joined the West”, but a people, much like the Russians, who have chosen in Kohl’s words the Europe of freedom over the Europe of dictatorship. It is why he was so keen to help suppress the people’s revolt in Belarus.

But it is also why Europe’s presidents and prime ministers could afford to be a lot less prissy.

Putin has already achieved what must be one war aim. He has smashed up a showcase for democracy – literally left smouldering and broken a nation that threatened to become a demonstration of an alternative to his kleptocracy. Let this practical hard truth inform the EU’s deliberations.

Even if the war stopped tonight, Ukraine would be in no fit state to join the EU in any practical way for years to come. Terrible to consider, but it may soon be obliterated as an independent nation, seeking a way to keep the flame alive in exile.

Is there, then, not a case for a dramatic, in-your-face, demonstration of solidarity from the EU? Some bold promise of speed and determination, temporary associate membership perhaps, as a rebuke and an affront to Putin? Allowing Ukrainian refugees rights to healthcare and travel is a great start – why not boast about it and label it “citizenship”?

That would be costly – other big symbols come almost for free. Maybe with some new substance, whether that be ministers regularly attending summits, a voice at the commission, or any one of a hundred better ideas. The beauty of it is the actual form doesn’t really matter.

What does matter is the EU wrapping its arms around Ukraine and sticking two fingers up to Putin. Then Europe may find its soul and in Zelensky’s words, “life will win over death and light will win over darkness”. Unlikely perhaps, simplistic even, but he’s a man who knows the worth of bold words and big symbols. Maybe, for once, it is a time for gesture politics.

Mark Mardell is a former BBC Radio 4 presenter, North America editor, Europe editor and chief political correspondent