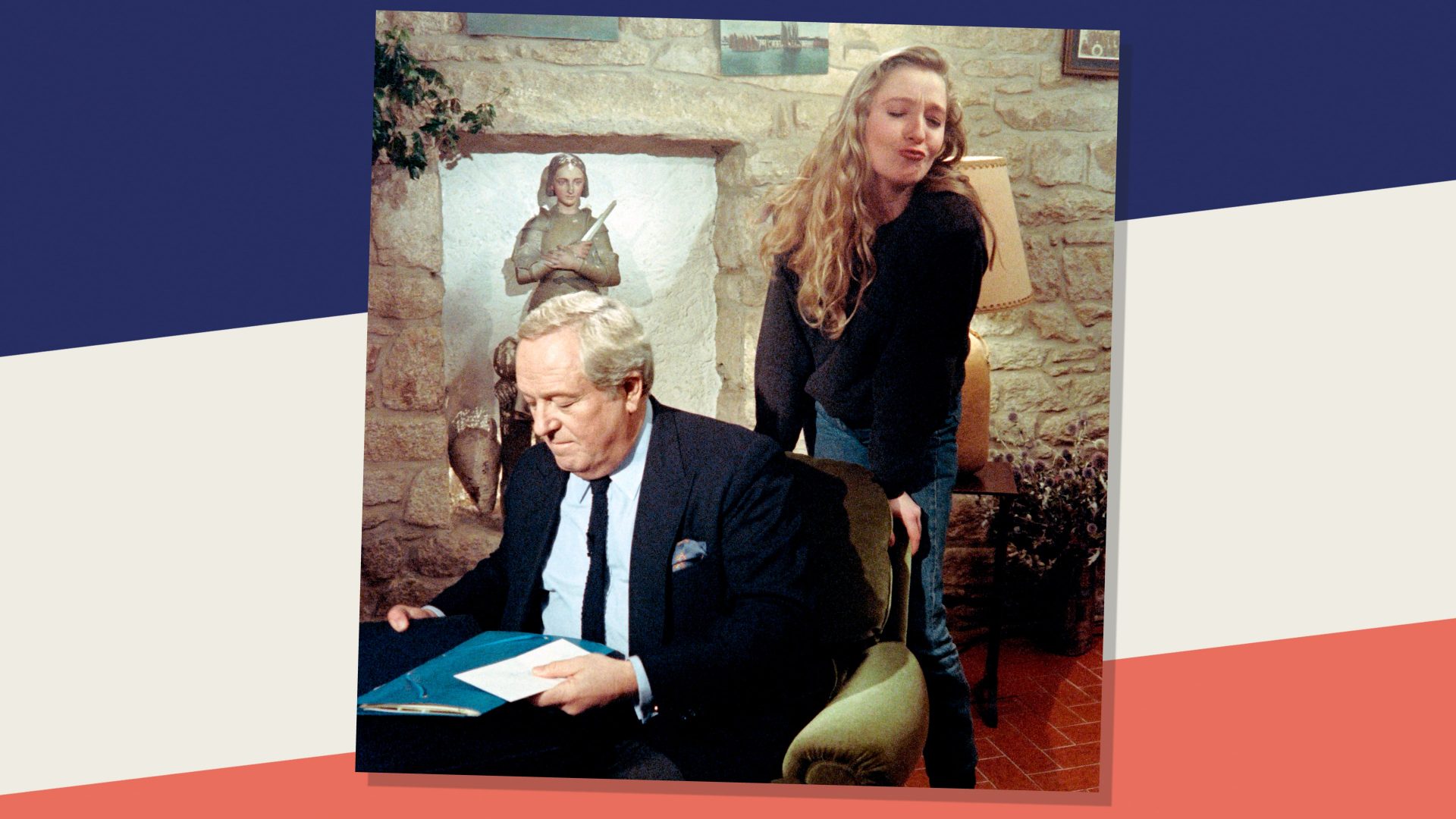

A few weeks before the 2017 presidential election, I interviewed Marine Le Pen at her campaign headquarters. As a provocation, she had named it “L’escale” (“The stopover”) and settled it in the same street as the Elysée Palace, rue du Faubourg Saint Honoré.

What she had in mind was to underline that her far right party, then called the National Front (to be renamed National Rally in 2018), was not so far right and no longer marginal. The balance of power was shifting at the time. The French political landscape was exploding slowly, paving the way for the total disappearance of the two major traditional parties of the right and the left, as nowhere else in Europe.

In the spring of 2017, François Hollande was president of France, Emmanuel Macron was not sure he would make it, the conservative François Fillon was being swept away by corruption scandals, the far left candidate, Jean-Luc Mélenchon, was taking over from the Socialist Party. Le Pen, buoyed by the polls, was beginning to believe that something that had never been conceivable in postwar France turned out to be possible: a far-right candidate being elected president of the Republic.

In Marine Le Pen’s office, a British flag sat at the foot of a poster showing two fists breaking free from their chains and the caption read “And now France!” The Brexiteers had won their referendum a few months earlier. Brexit was for her a tangible sign, she told me, that “the whole world is turning its back on free trade and savage globalisation”.

In the spring of 2017, she was preparing to face Macron for the first time in the second round, and with visible satisfaction she sketched out to me a portrait of him. “Macron is the ideal opponent for me,” she boasted. “A young technocrat, a former banker at Rothschild, who does not know the real country and confuses Paris and Brussels… he is the caricature of the elites and the ‘system’, of everything I fight and everything the French no longer want. No, really, I can’t hope for anything better than Macron!”

Shortly afterwards, she lost to him in the second round, by 34% to 66%. But this was already almost double the votes won in 2002 by her father, National Front founder Jean-Marie Le Pen, who had caused a national trauma by coming in ahead of the Socialist candidate, Lionel Jospin, in the first round before being routed by Jacques Chirac. The “republican front” which, under the shock of 2002, had mobilised right and left for an “Anything but Le Pen”, was already showing signs of weariness.

The continued rise of Marine Le Pen is the result of a patient strategy of “de-demonisation” of the party and of her person. Le Pen is no longer just a family name. “Marine” has become a brand name and even the initial of her official website, “M la France”.

She has finally discarded her father, Jean-Marie Le Pen, a figure of the extreme right, fed by former admirers of Marshal Pétain, supporters of French Algeria hating De Gaulle and antisemitic remnants. While discreetly keeping some of its most extremist supporters, she kicked her father out of the party.

She has taken advantage of the nationalist-populist wave that has swept through the West. The Brexit triumph was followed by Donald Trump’s in the US, then by a third re-election of Viktor Orbán in Hungary, then by Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil and Matteo Salvini in Italy. She has praised Trump and pampers Steve Bannon, former strategic adviser to the former US president, who is plotting a global union of populist nationalists. She went to the Kremlin and broadcast, visibly exhilarated, the images of her meeting her mentor and idol Vladimir Putin, who honoured her like a stateswoman. Brexit leaders – Boris Johnson and even outsider Nigel Farage – have kept her cautiously at arm’s length and avoided appearing with her, aware that an alliance with Jean-Marie Le Pen’s party, with its antisemitic and racist roots, could do them a disservice.

But they have much in common. They all understood how globalisation was an asset for them: nations have lost their bearings, the internet has blurred the difference between truth and “alternative facts”, social networks have abolished the hierarchy between the people and the elites, and have made emotion the supreme value. Lying could become a political strategy. Populism is an magic trick: these illusionists succeeded in making people believe they were giving back to the nation “control” while they embodied “the will of the people”. Whether they themselves were billionaires (Trump), old Etonians (Johnson) or wealthy heirs (Le Pen).

In line with her strategy of de-demonisation, Marine Le Pen wants to make people forget her extremism and iron out her duel with Emmanuel Macron to a basic opposition between the arrogant elite she claims he is and the oppressed people she pretends to embody. She had the right intuition to focus on “purchasing power”, which is the number one priority of the French, when the president was accused of being “the president of the rich”, then busy with the war in Ukraine. Less aggressive in her interviews, she tries to pass for the wise person above the fray, says she wants to preside over France “as a good mother”, posts lots of pictures of her with cats, caressing them as she does her voters.

A victim of “Anyone but Le Pen” in 2002 and 2017, she intends to take advantage of the “Anyone but Macron” sentiment that is now widespread both on the right and on the left. Between Le Pen and Macron, the roles are reversed and the differences are blurred: she is no longer the pushover – he has become one, too. He is no longer the unknown disruptor. She is the newness. Her far right rival Eric Zemmour was so radical he made her look moderate and now, placing herself “close to the people”, she even appropriates the Macronian “at the same time” by claiming to be, like him, “neither of the right nor of the left”.

These are just words. Marine Le Pen is rightly banking on the fact that the majority of voters trust her speeches without reading her programme. She no longer wants to be far right, but only “national right”. Since Putin started his war crimes in Ukraine, she’s been trying to distance herself from him and has felt compelled to destroy millions of election pamphlets with a picture of them hugging each other in the Kremlin.

Since her disastrous 2017 debate with Macron, in which she completely failed to show the value of leaving the EU and the euro, she has made a U-turn, at least in words. She no longer says she wants to leave the EU, but her whole programme says the opposite. She says she is attached to the rule of law, but everything in her programme shows how close she is to the “illiberal democracy” of her old pal, Viktor Orbán. The Marine Le Pen of 2022 remains a masked Frexiteer and a right wing extremist in camouflage.

An award-winning journalist, Marion van Renterghem writes for L’Express, The Guardian and The New European