In 2013 Bernardo Bertolucci sat on a stage in Paris and recalled the infamous butter scene between Marlon Brando and Maria Schneider in his 1972 film Last Tango in Paris.

He described how he and Brando had devised the scenario on the morning it was shot, effectively a rape scene involving Brando’s and Schneider’s characters in which a packet of butter is grimly significant. He set out how he and Brando conspired to keep the plan from Schneider when she arrived on set, leaving her unprepared and unsuspecting when the cameras rolled. Bertolucci explained to a rapt audience how he wanted to capture her reaction “as a girl, not as an actress”, and how he needed her “to react humiliated”.

“I think she hated me and also Marlon because we didn’t tell her,” he mused,

adding that he had no regrets about his conduct.

“To obtain something in art I think you have to be completely free,” he said. “I didn’t want Maria to act her humiliation, her rage, I wanted Maria to feel the rage and humiliation.”

When Bertolucci spoke, Schneider had been dead for two years. She had no

agency on the day of filming and no agency on the day the director discussed it on stage in front of an audience. She spoke publicly of the scene and its inception only once.

“I should have called my agent or had my lawyer come to the set because you

can’t force someone to do something that isn’t in the script, but at the time I didn’t know that,” she said in 2007. “Marlon Brando said to me, Maria, don’t worry, it’s just a movie, but during the scene, even though what Marlon was doing wasn’t real I was crying real tears. I felt humiliated, and to be honest I felt a little raped, both by Marlon and by Bertolucci.”

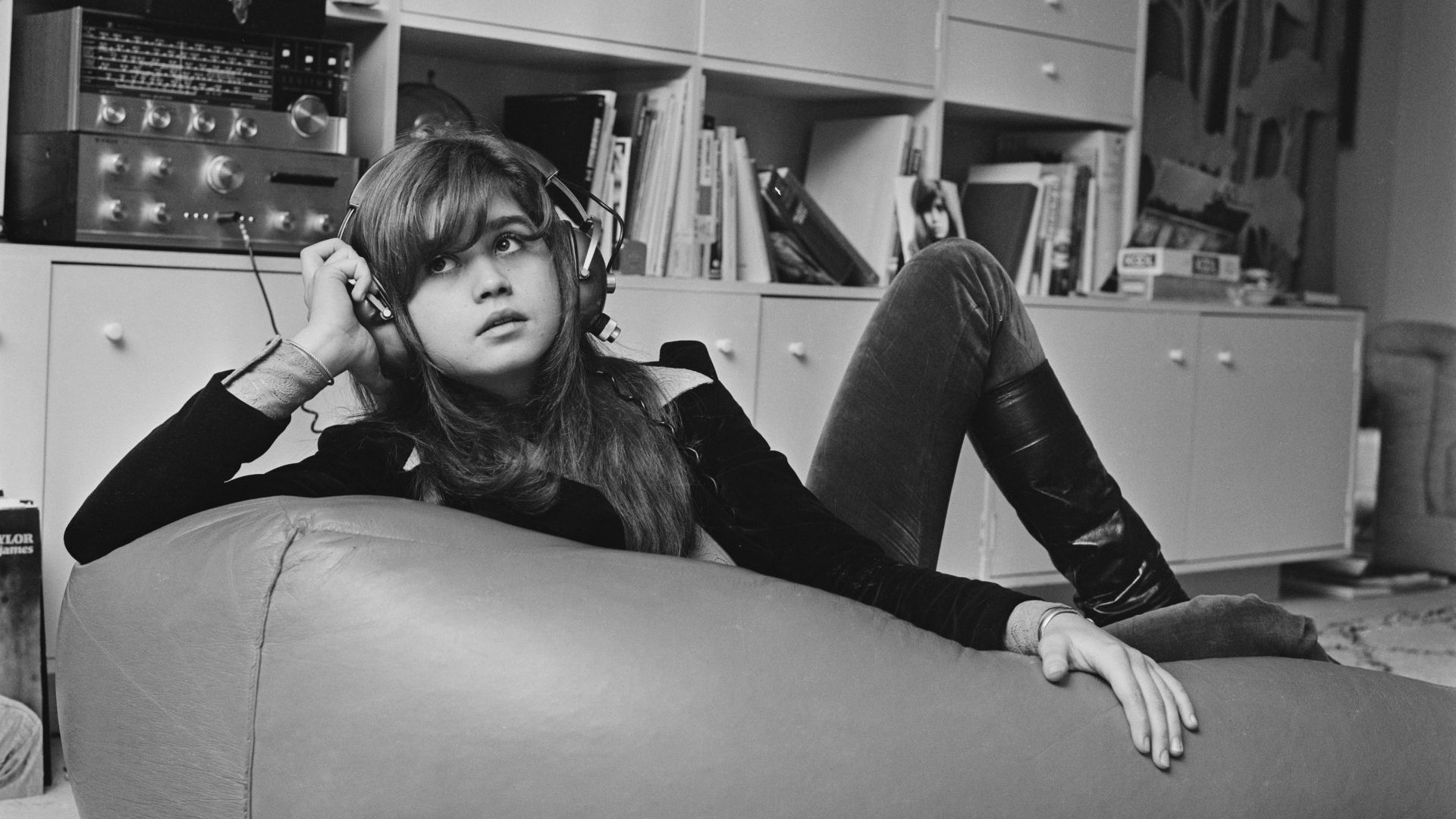

Still a teenager during filming and with limited screen experience when cast opposite the 48-year-old Brando, Schneider was as ill-equipped for the impact Last Tango in Paris would make on the world of cinema as she was for the personal impact it would have on her.

Notorious for the explicit scenes between Brando’s Paul, a world-weary

American widower, and Schneider’s vivacious young Parisian Jeanne as they

fell into an intense affair after meeting while viewing an apartment, only Schneider was required to appear nude. The film’s explicitness prompted protests and legal action from Christian groups in the United Kingdom and in Italy the producer, director and leading actors were given two-month suspended prison sentences in absentia.

Brando, a year after The Godfather, was hailed for the depth and gravity of his

performance. Bertolucci was called a genius, with the New Yorker’s legendary film critic Pauline Kael predicting Last Tango in Paris would have the same cultural impact as the 1913 premiere of Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring.

Schneider, meanwhile, despite positive mentions in many reviews, found herself cast in a wholly different light, called “the pin-up girl of a decadent decade” and “the establishment Linda Lovelace” in reference to the star of the pornographic Deep Throat, released the same year.

“I felt very sad because I was treated like a sex symbol,” she said. “I wanted to be recognised as an actress and the whole scandal and aftermath of the film turned me a little crazy and I had a breakdown.”

Any young actress might have struggled in Schneider’s shoes but few would have set out with her vulnerabilities.

She was born in Paris to a 17-year-old bookseller and part-time model named

Marie-Christine Schneider, the result of an affair with married French actor

Daniel Gélin. Although Maria was always aware of her father’s identity, he refused to acknowledge her as his daughter and they didn’t meet until Schneider surprised him one day in her mid-teens.

“When we met he was not nice,” she recalled. “He exists but means nothing to me.”

Placed with a nurse for two years of her early life, Schneider spent most of her childhood with her uncle’s family in Alsace, close to the German border. At 15 she set out for Paris, becoming effectively homeless and eking out a living as a film extra until a chance on-set conversation with Brigitte Bardot changed her life.

Appalled by Schneider’s tale of parental neglect, Bardot, who had worked with Gélin, took Schneider under her wing, putting her up, recognising her talent and introducing her to major players in the film business. It was Warren Beatty who, as a favour to Bardot, persuaded the William Morris agency to take on Schneider as a client.

Her role in the 1970 Alain Delon vehicle Madly got her noticed and she had accepted another part opposite Delon when the offer came through for Last Tango in Paris. Schneider’s friend Dominique Sanda had been cast but withdrew when she became pregnant; Bertolucci saw a picture of the two women together and immediately called Schneider.

Despite her wish to honour the existing commitment, her agents insisted the

opportunity to star opposite Brando was too important to pass up.

“When I read Last Tango In Paris I didn’t see anything that worried me,” she said. “I didn’t want to be a star, much less a scandalous actress, simply to be in cinema. Later, I realised I’d been completely manipulated.”

The experience exacerbated a spiral into addiction, depression and ultimately a suicide attempt, with Schneider speaking openly in interviews of taking heroin and cocaine.

“I started using drugs when I became famous,” she recalled in the 2000s. “I did not like the celebrity and especially the image full of innuendo that people had of me after Last Tango.”

While Brando and Bertolucci continued to be feted for their art, Schneider couldn’t go into a restaurant without being “looked at like an animal, especially by old men with shiny eyes”, yet she still did her best to defend her

performance and the film, sometimes hinting at her own predicament.

“It is not a pornographic movie,” she said in 1973. “It is about loneliness and anguish.”

Good, challenging roles became scarce, not least when she made it clear nude scenes were now out of the question. She regarded her performance in 1975’s The Passenger as her best, but when co-star Jack Nicholson acquired the rights after its initial run he kept the film under wraps and unseen for three decades.

Renowned for walking off sets, sometimes for artistic reasons (the less

said about Tinto Brass’s Caligula the better), sometimes for personal reasons

(she abandoned 1975’s The Baby Sitter to check herself into a psychiatric hospital in Rome where her then partner, the photographer Joan Townsend, was being treated), work became harder to find and in her later years Schneider devoted as much time to using her story to help others as acting.

There was one particular piece of advice she gave that she wished she’d

received when starting out.

“Never take your clothes off for a middle-aged man who claims that it’s art.”