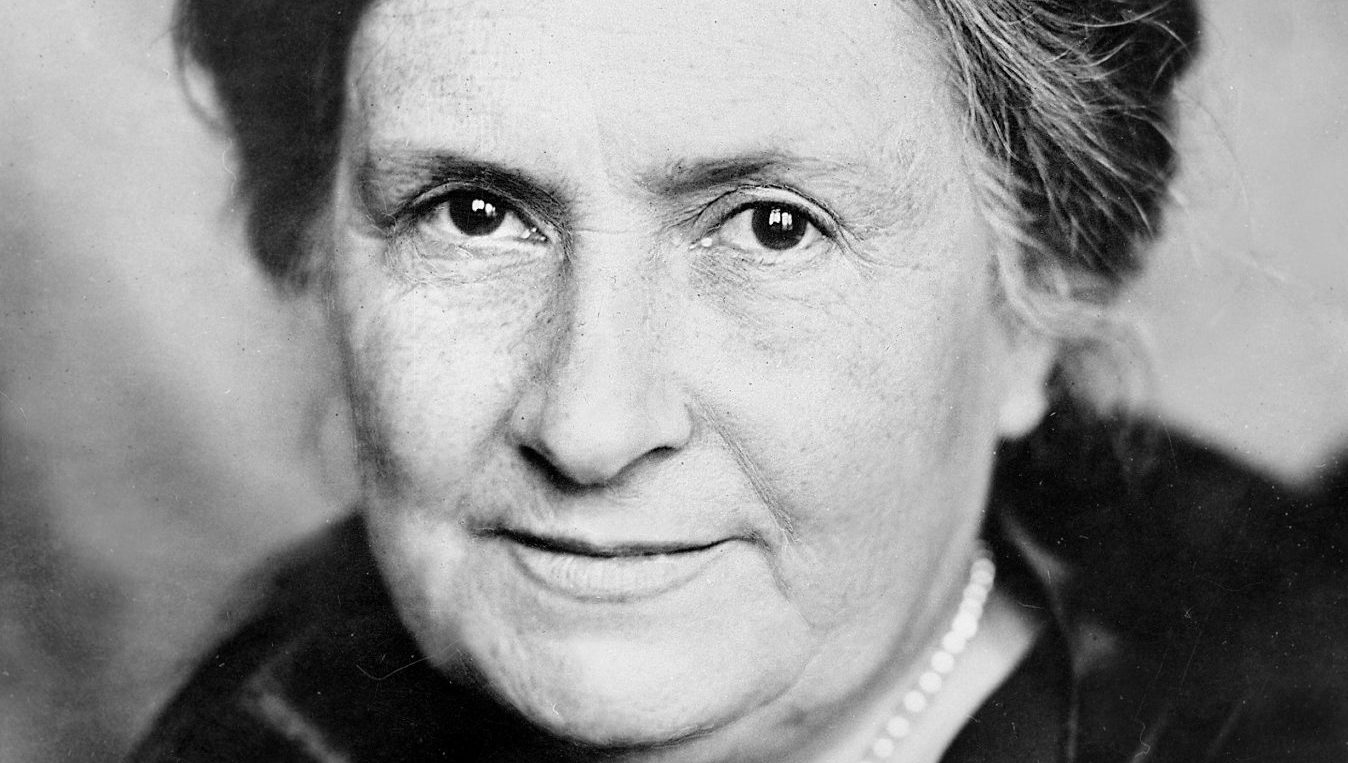

In the autumn of 1897, Maria Montessori was already building an impressive career when she discovered she was pregnant. The 27-year-old had worked hard to establish herself as a doctor and was in the process of applying those skills to the field of teaching children with special needs when the realisation came.

Only recently graduated, the implications of motherhood were profound: she was in a relationship with Giuseppe Montesano, a fellow doctor, and custom dictated the couple should marry.

Marriage, however, would have been disastrous. For one thing, Montesano’s family were dead against the idea. Most importantly, matrimony would mean an immediate end to Montessori’s working life, because in the Italy of the 1890s, married women did not do anything as vulgar as work for a living.

While aware of her obligations to the patriarchy, Montessori felt her world crashing around her. It was only when she sought the counsel of her mother that the way forward presented itself.

“You have done what no other woman has ever done in Italy,” Renilde Montessori, a woman whose own teaching career had been ended by marriage, told her. “You are a scientist, a doctor, you are everything. Now because of a baby you could lose everything.”

It was an almost impossible choice, one faced by generations of women, but Montessori and Montesano agreed that if they couldn’t marry, neither of them would marry anyone else. Their son Mario spent his early years with a family in a village outside Rome, receiving occasional visits from his mother that were clandestine by necessity.

Montessori had already battled against the odds to carve out a career of which she felt she was still only on the threshold. After early ambitions to be an engineer in an era when teaching was seen as the only realistic career option for a woman, Montessori chose to pursue a career in medicine, graduating in 1892 from the University of Rome with a degree in natural sciences before enrolling as a medical student the following year.

Being the only woman on the course, the first in the history of the institution, tutors and fellow students felt her presence during the study and dissection of naked human corpses to be improper and Montessori was forced to study cadavers alone. She took up smoking purely for the tobacco smoke to mask the smell of decay and formaldehyde.

She graduated in 1896 as only the third woman in the history of Italy to qualify as a doctor. The same year she represented her country at the International Women’s Congress in Berlin, delivering an address on the necessity of working women receiving equal pay to their male counterparts, and took a job as an assistant doctor in the psychiatric department at the university hospital in Rome.

Given her student specialism in paediatrics, Montessori was asked to make regular visits to Rome’s largest asylum in order to assess the children. She found many with serious mental disorders but noted that others were simply malnourished or neglected, a situation exacerbated by what was effectively incarceration.

When she heard the children being condemned as gluttonous because they scrambled around on the floor looking for breadcrumbs after their meals, Montessori became convinced they were simply bored. Locked in an empty room with only straw to sleep on, the crumbs were the only objects available for any kind of stimulation.

This observation set Montessori on a course to revolutionise children’s education and establish the schools that carry her name all over the world to this day.

In 1900 she became co-director of Rome’s Orthophrenic School, the first institution to teach children with special needs. The outcomes were excellent with many children written off as mentally weak achieving exam results as good as their peers in conventional schools.

Montessori’s philosophy was that children wanted to learn and wanted to work but were stifled by a rigid education system with no scope for individual development. When she noticed the young children at the school discarding toys donated by well-wishers in favour of returning to objects that aided their learning, it was a vindication.

“That’s when I understood that perhaps play was something inferior in the lives of children,” she wrote, “and that they resorted to it for lack of anything better to do.”

Montessori devised a series of objects stimulating to children – clay, wooden blocks, pencils, letters of the alphabet made from sandpaper – that taught mathematics and reading by allowing them to work things out for themselves, eschewing traditional rote teaching in organised ranks of classroom desks where the pupils were like “butterflies mounted on pins”.

As she honed her method, Montessori noticed how, when left to their own devices, the children concentrated for longer periods, working on their own, learning individually rather than collectively.

“We observe something strange,” she wrote. “Left to themselves the children work ceaselessly and after long and continuous activity their capacity for work does not appear to diminish but to improve.”

In 1906 she received financial backing to open her first purpose-built premises, the Casa de Bambini, House of Children, in Rome’s poverty-stricken San Lorenzo district. The school was designed to give pupils aged three to six as much scope for learning as possible.

From bathroom sinks to stairs, the facilities were constructed at a scale appropriate for children, who wore practical aprons and sandals easy to put on and take off themselves. Even the tables and chairs were designed to be easy to rearrange.

The success of Casa dei Bambini saw it christened “the miracle of San Lorenzo” by the press and before long Montessori schools were springing up all over the world to reports of extraordinary success. By 1913 Montessori was lecturing at Carnegie Hall in Manhattan and visiting a Montessori school set up in New York by Alexander Graham Bell.

After a brief flirtation with fascism during the 1920s, initially detecting common ground between Mussolini’s ideals and her stated desire to “perfect the human race”, she became horrified by the regime’s brutal philosophy. She became such a vocal anti-fascist that her books were burned in Berlin in 1933 and three years later Mussolini closed every Montessori school in Italy.

Their founder spent the rest of her life dividing her time between India, where she instructed more than 1,500 teachers, and the Netherlands, instilling in all her trainees the mantra that underpinned everything.

“What really makes a teacher is love for the human child; for it is love that transforms the social duty of the educator into the higher consciousness of a mission”.