“Iconic” is a word that suffers gross misuse these days, but the Trevi Fountain scene in Federico Fellini’s 1960 film La Dolce Vita is a rare example

of its appropriate use. Marcello Mastroianni plays disillusioned journalist Marcello Rubini, who finds himself squiring a Swedish-American film star named Sylvia, played by Anita Ekberg, alone through the deserted streets of late-night Rome.

After Sylvia dispatches Marcello to find milk for a street kitten, he returns to find her wading into the Trevi fountain. She insists he join her, so Marcello removes his shoes and socks and finds himself sloshing thigh-deep through the water towards Sylvia, statuesque beneath a cascade, head back, eyes closed.

He stands before her, overwhelmed by her beauty, especially against the aesthetic perfection of the fountain itself. He raises his hands towards her

face, tracing its shape but not touching, saying her name. Their heads move

almost imperceptibly closer in a moment of near unfathomable sensuality. Sylvia opens her eyes, reaches down, lifts her arm and sprinkles water on top of Marcello’s head, like an anointing. Then the flow of water stops and there is silence. A wide shot shows a baker’s delivery boy astride his bike, empty tray held on his head, staring at them. The night is over, a new day begins.

It takes up not even two minutes of screen time but that scene has become

one of the most unforgettable moments in the history of cinema. It took three nights to film, nights when Mastroianni was, according to Fellini, “completely hammered”.

He didn’t mean to be. The film might have been set during the hot Roman

summer but shooting took place at the tail end of a harsh winter, something

with which Ekberg coped far better than her leading man.

“She didn’t feel anything,” Mastroianni recalled. “She was Swedish, used to diving into icy water as a child.”

Mastroianni, on the other hand, needed all the help he could get. “He had to get undressed, put on a frogman’s suit and get dressed again,” Fellini said. “Also to combat the cold he polished off a bottle of vodka.”

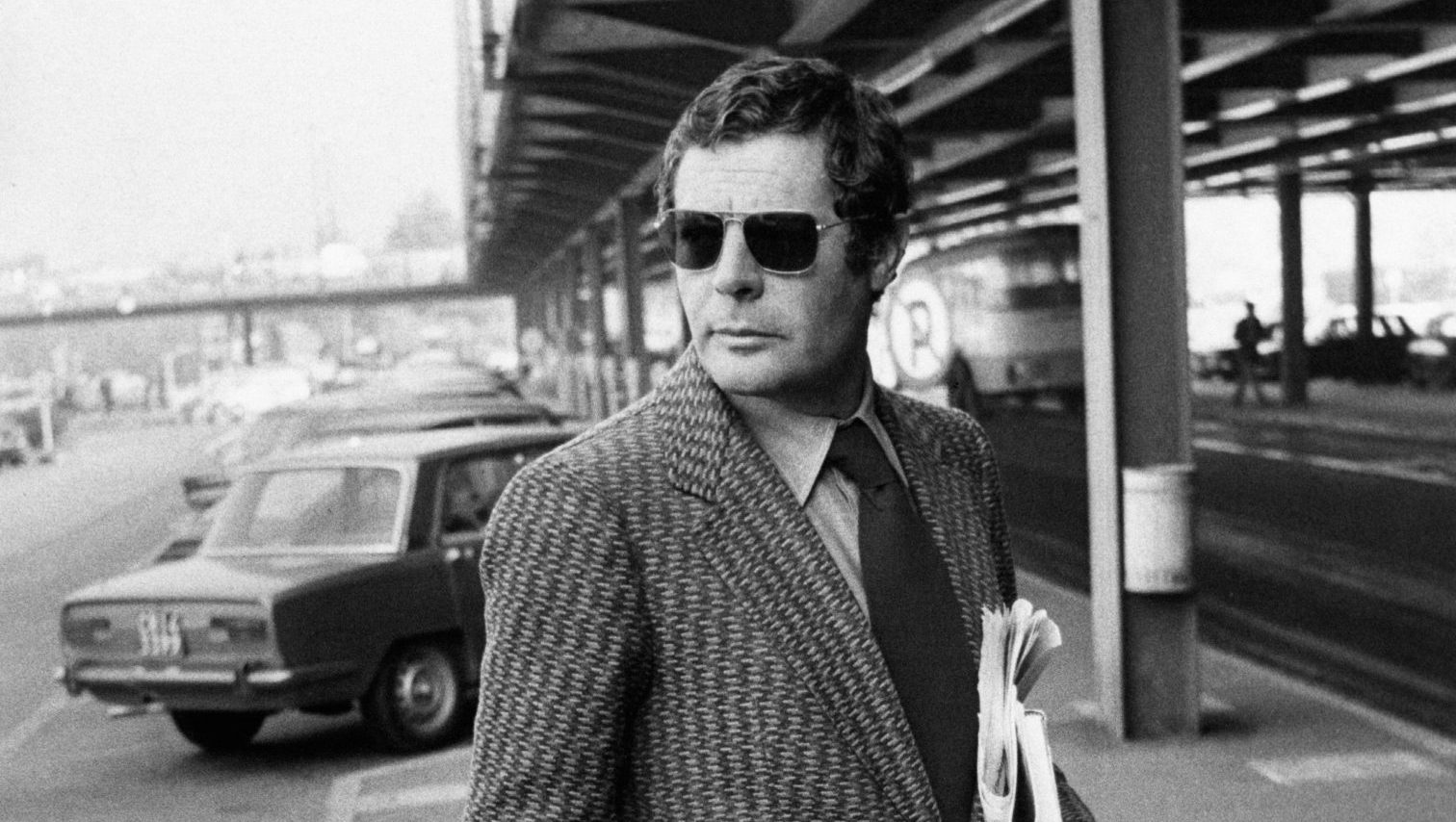

Drunk or not, his unforgettable performance in La Dolce Vita established Mastroianni as the archetypal Italian leading man, one who would go on to star opposite a host of cinema’s most beautiful women, including eight films opposite Sophia Loren alone.

Yet there was more to Mastroianni on screen than charm and a gift for seduction. His characters had a vulnerability about them, betraying a trace of the little boy they once were. He played disillusioned men retaining a

spark of optimism that there might yet be an epiphany, something to make it

all worthwhile. His was acting of remarkable subtlety and nuance, a screen presence that took immense skill, especially when sharing the screen with some of cinema’s most magnetic women.

Yet Mastroianni always played down his craft, not least the perception of him as hero or heartthrob.

“My legs are skinny, my face has no power or resolve,” he insisted when asked how he compared to the likes of Clark Gable, Gary Cooper, Humphrey

Bogart or Paul Newman. “They knew where they were going, or at least we

presumed they knew. I, on the other hand, have no idea where I’m going.”

He had no truck with method acting either, asking: “If a role requires you to

play the violin do you spend ten years learning to play the violin? Come on. That is the beauty of cinema: everything is false. And sometimes it is more real than reality”.

He was happy to describe himself as indolent when it came to accepting and

working on roles and refused almost all offers from outside Italy on the grounds that, as he explained in 1962: “The best films in the world are made in Italy so why would I go anywhere else?”

Fellini was among those who knew him well enough to shatter such deprecatory self-mythologising.

“The legend that Marcello is indifferent or lazy is nonsense,” he said in 1993. “He spends hours discussing his role until he thoroughly understands it, extracting the most extraordinary nuances. When he has it inside him and he trusts his director we can get what we’re really after: a look at the inner reality of life.”

Certainly the fact that he kept working until just a few weeks before his death from pancreatic cancer at the age of 72, touring Italy in The Last

Moons, a play about heartbreak and old age, counters any suggestion of indolence. Likewise, he retained his fierce determination to succeed that had endured even when it looked like stardom would remain out of reach.

The son of a cabinetmaker, Mastroianni fostered early ambitions to be an architect, his draughtsmanship leading to conscription in 1943 to draw maps for Mussolini’s retreating armies. After the Germans occupied Italy, Mastroianni was sent to the north of the country where he was put to work

digging ditches. When he got word early in 1944 that he was to be transferred to a labour camp in Germany, he forged some papers and escaped with a friend to Venice, where he hid out until the end of the conflict.

“It was a bohemian time in some respects, and I sometimes let myself grow nostalgic about it,” he said, “but it was a bitter time also.”

He returned to Rome, resumed his studies, worked as a clerk at a film studio and took as many acting jobs as he could, working his way up from crowd scenes in films to a position where he was rarely short of opportunities on stage and screen. Somehow, though, he couldn’t seem to land the leading roles for which he was sure he was destined.

By the late 1950s he’d established himself in character parts but not making the impact he’d hoped for. He was over 30 and he could see his career aspirations slipping away as a new generation of actors began to overtake him.

“So I scraped together some money and produced a film with Visconti,” he said in 1965. “His last ones had been failures but he was brilliant with actors

and very artistic for the festivals. In 1957 we did a Dostoevsky story called Le notti bianche (White Nights). He called it neo-Romanticism. Very arty. I won the Nastro d’Argento, the Italian Oscar, for best actor and everyone said:

‘Mastroianni, he’s not bad.”’

Soon afterwards Fellini cast him in La Dolce Vita, apparently liking the actor’s

“terribly ordinary face”, then made Mastroianni the lead in his semi-autobiographical 81⁄2, his favourite of all his roles and one that confirmed his reputation as one of Italy’s finest actors.

On the night of Mastroianni’s death, a crowd gathered at the Trevi, silently

with candles. The city authorities dimmed the lights and turned off the fountain in tribute. The pinprick reflections of candle flames danced silently on the surface of the water as a flautist played the theme from 81⁄2.

“Cinema is a particularly fortunate profession,” Mastroianni had said a few

months before he died, “for in it I remain in perpetual infancy.”