“I am not dead, I am in Herne Bay.”

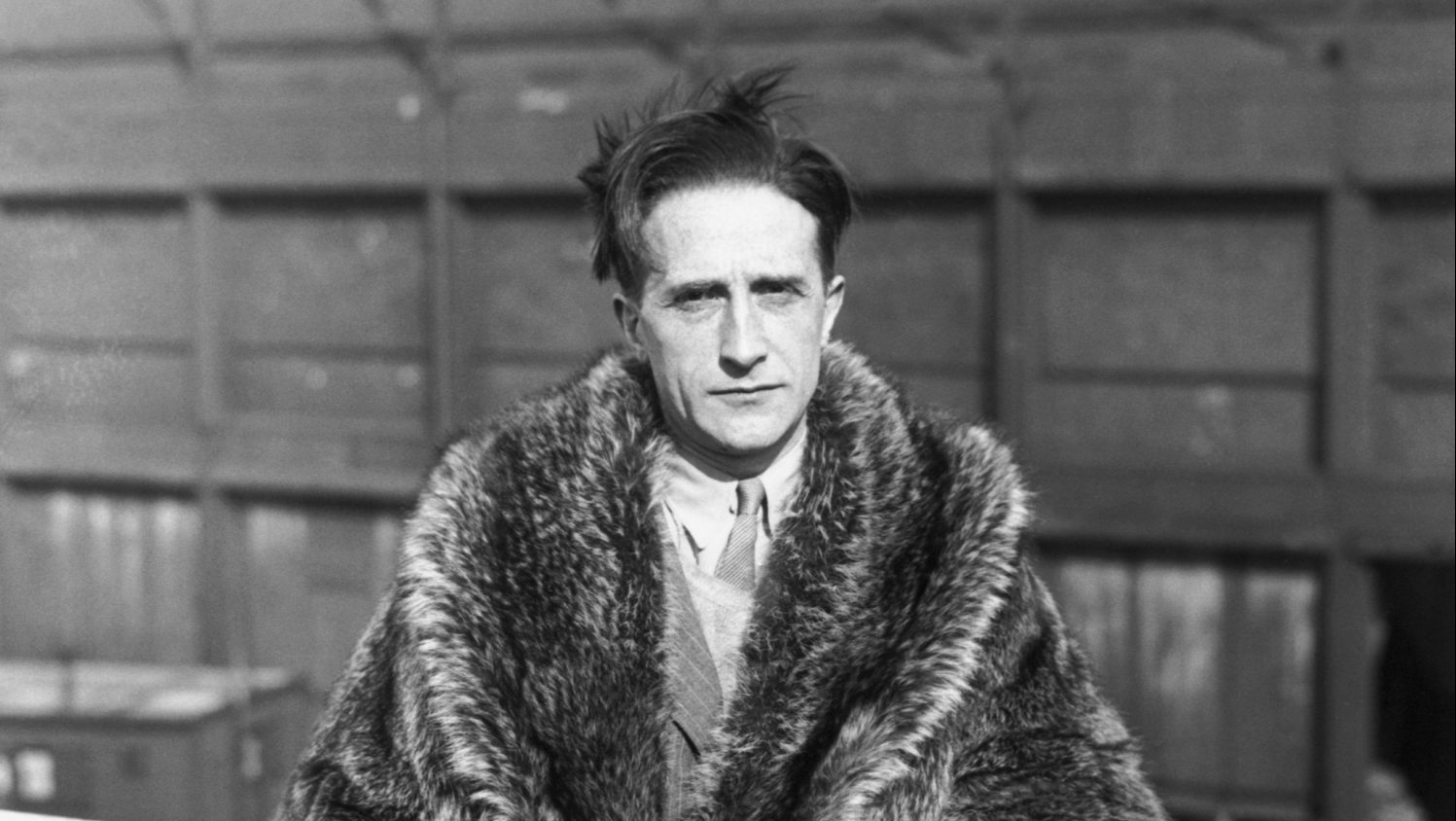

On August 6 1913, Marcel Duchamp sent this reassuring message on a postcard to his friend, the painter Max Bergmann, from the small seaside

resort in north Kent where his sister Yvonne was taking a residential English

language course. It hadn’t been the easiest summer for the pioneer of surrealism, dadaism and cubism, causing friends to become a little concerned at his absence from Paris.

They needn’t have worried; he was healthily occupied on the tennis court

and exploring the delights of the Kent coast. That evening Duchamp could

have gone to see Wilf Burnand’s impersonations of contemporary actors at the Central Hall, for example, or The Reluctant Cinderella at the Grand Cinema. Herne Bay was a busy place during that last golden summer before

the first world war and proving to be the tonic Duchamp needed.

“The traveller is enchanted,” he wrote to another friend a couple of days later. “Superb weather. As much tennis as possible. A few Frenchmen for me to avoid learning English, a sister who is enjoying herself a lot.”

It’s hard to believe that even as Duchamp dozed in a deck chair with a military band parping away on the bandstand nearby, he was at the heart of

one of the greatest and most controversial artistic explosions in modern culture.

Barely three months earlier he had been at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées

in Paris for the premiere of Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring. Choreographed by Nijinsky and performed by Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes, this was a performance so avant-garde and revolutionary the evening soon descended into uproar, the show all but drowned out by whistles, catcalls and loud arguments between audience members. It was an epoch-making

moment in the story of the 20th century and there, in the second row, sat an

enthralled Marcel Duchamp.

Most significantly, a few weeks before that his painting Nude Descending a

Staircase, No. 2 had scandalised the American art world when exhibited at the 69th Regiment Armory in New York in what became known as the Armory Show. Many of the works displayed were Americans’ first taste of European impressionism and cubism and of all the exhibits it was Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 that garnered the most attention, not much of it complimentary.

A succession of overlapping figures descending from the top left to bottom

right of the canvas, thus giving the impression of motion, Nude… is a clutch of superimposed cones and cylinders barely discernible as individual human figures but which, when viewed together, create a discernible grace in motion.

“My aim was a static representation of movement,” said Duchamp, “a static composition of indications of various positions taken by a form in movement with no attempt to give cinema effects through painting.”

Americans were as baffled as they were appalled. The New York Times cited the tale of The Emperor’s New Clothes and compared Duchamp’s work to “an explosion in a shingle mill”. Despite the painting’s scurrilous title, “the canvas is one that could be hung up in Methodist Sunday school, and if it did any harm there it would be to the minds of the pupils, not their morals”.

Even the US president, Theodore Roosevelt, weighed in, crediting a Navajo rug hanging in his bathroom as “a far more satisfactory and decorative picture… from the standpoint of decorative value, of sincerity, and of artistic merit, the Navajo rug is infinitely ahead of this picture”.

When the exhibition moved on to Chicago, the director of the venue advised visitors to “whirl around three times, bump your head against the wall twice and if you bump hard enough the painting will become perfectly obvious”. When word of the painting’s reception reached Paris, the criticism hit Duchamp hard.

“I am very down at the moment and doing absolutely nothing,” he’d written to Walter Pach, organiser of the Armory Show, in July 1913. “It’s very irritating when things are like this. I am going away in August to spend some time in England.”

His month in Herne Bay had a revitalising effect. Leaping around a tennis court or sitting on the beach looking out at the North Sea he felt as far as possible from the brouhaha of the Armory Show and took the opportunity to rest and take stock.

Promising signs seemed to be everywhere.

On August 7 he was one of hundreds of people who climbed up to the top of the cliffs to examine a Short biplane that had landed there, reminding Duchamp of the aviation expo he’d attended in Paris a few months earlier where he admired the design of the aircraft and told a friend, “Painting’s finished. Who’ll do anything better than that propeller?”

When he stood on the cliffs and watched the plane take off, bank out over the sea and shrink to a distant speck, he realised that painting would play a much smaller part in whatever came next.

A new job awaited him in Paris as a librarian at the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, but when he boarded the steamer for Calais at the end of the month he already had four annotated drawings in his valise that formed the basic elements of another signature creation, The Large Glass, an abstract on two glass panels nine feet by six, on which he would keep working until 1923.

In 1915 Duchamp began producing his “Readymades”, what he called “everyday objects raised to the dignity of a work of art by the artist’s act of choice”. First, there was Bottle Rack, then a snow shovel presented as In Advance of the Broken Arm, followed by his most famous creation, The Fountain, a porcelain urinal signed with an artist’s signature “R. Mutt”.

In 1919 came L.H.O.O.Q., a souvenir print of the Mona Lisa on which Duchamp had inked in a cartoon moustache and beard and added the hand-printed letters of the title. When said aloud the title in French sounds very close to “elle a chaud au cul”, or “she is hot in the arse”, mooting a possible explanation for La Gioconda’s enigmatic smile.

The Large Glass, when completed, proved to be his last major work, as from 1923 Duchamp detached himself from the studio in favour of the chess board. An excellent chess player, good enough to make the French national

team and compete in the international Chess Olympiads, the game sustained

him for the rest of his life. He wrote newspaper columns, devised puzzles,

carved his own sets and staged the occasional artistic chess-related

endeavour: a few weeks before his death he played the composer John Cage on a board wired to a synthesiser that triggered musical notes with each move.

He still dabbled in the art world, becoming a noted curator of exhibitions, but the last four decades of Marcel Duchamp’s life were focused almost entirely on the chess board.

“Why isn’t chess an art activity?” he wondered in 1956. “A chess game is very plastic. You construct it, it’s mechanical sculpture. With chess, one creates

beautiful problems and that beauty is made with the head and hands.”