Most English placenames were established long ago, well before the Norman Conquest, during the time when the language of the country was Anglo-Saxon (Old English), which is no longer readily intelligible to modern English speakers. Coupled with the fact that many linguistic changes have taken place in the forms of names over the last 1,000 years, this has led to a situation where placenames which would originally have had a rather clear meaning no longer necessarily do.

Redcar in Yorkshire originally meant “reedy marsh”, but there is no way today that anyone without specialist onomastic knowledge can know that – though there are exceptions.

Playford in Suffolk is one of those villages whose name does actually mean what it says: it does have a ford, which crosses the River Lark (see also TNE #397); and it really was a place where games used to take place – where people used to play.

The same was probably not true of Playden in Sussex, where the play element is thought to have come from the personal name Plega – the ford would have belonged to or been under the control of a man who bore that name. But in the Suffolk toponym Playford, which appears in the Domesday Book as Plegeforda, the first part of the name does actually come from Old English plega “to play”.

Not very far away from Playford, and also on the River Lark, is the village of Lackford, which we also discussed in TNE #397. We saw that this name could perhaps have originated in an Anglo-Saxon name meaning “ford where leeks grow”, the Old English word for “leek” being lēac.

But Lackford could equally well have come from the Anglo-Saxon verb lácan “to play”, an ancient word which has survived in Yorkshire and other areas of formerly Viking northern England (where it was reinforced by Old Norse) as in laking, to lake “playing, to play”. The English Dialect Dictionary shows this “play” meaning as occurring in Northumberland, Durham, Yorkshire, Cumbria, and northern Lancashire. Interestingly, at one time the word was also found as far south as Gloucestershire. It occurs in Scots, too, where it can be written laike.

Another form of this word is employed in English as the technical ornithological term lek (see box), and is probably best regarded not as an Anglo-Saxon survival, nor as a borrowing from Viking Old Norse, but as a loan from modern Swedish leka “to play”.

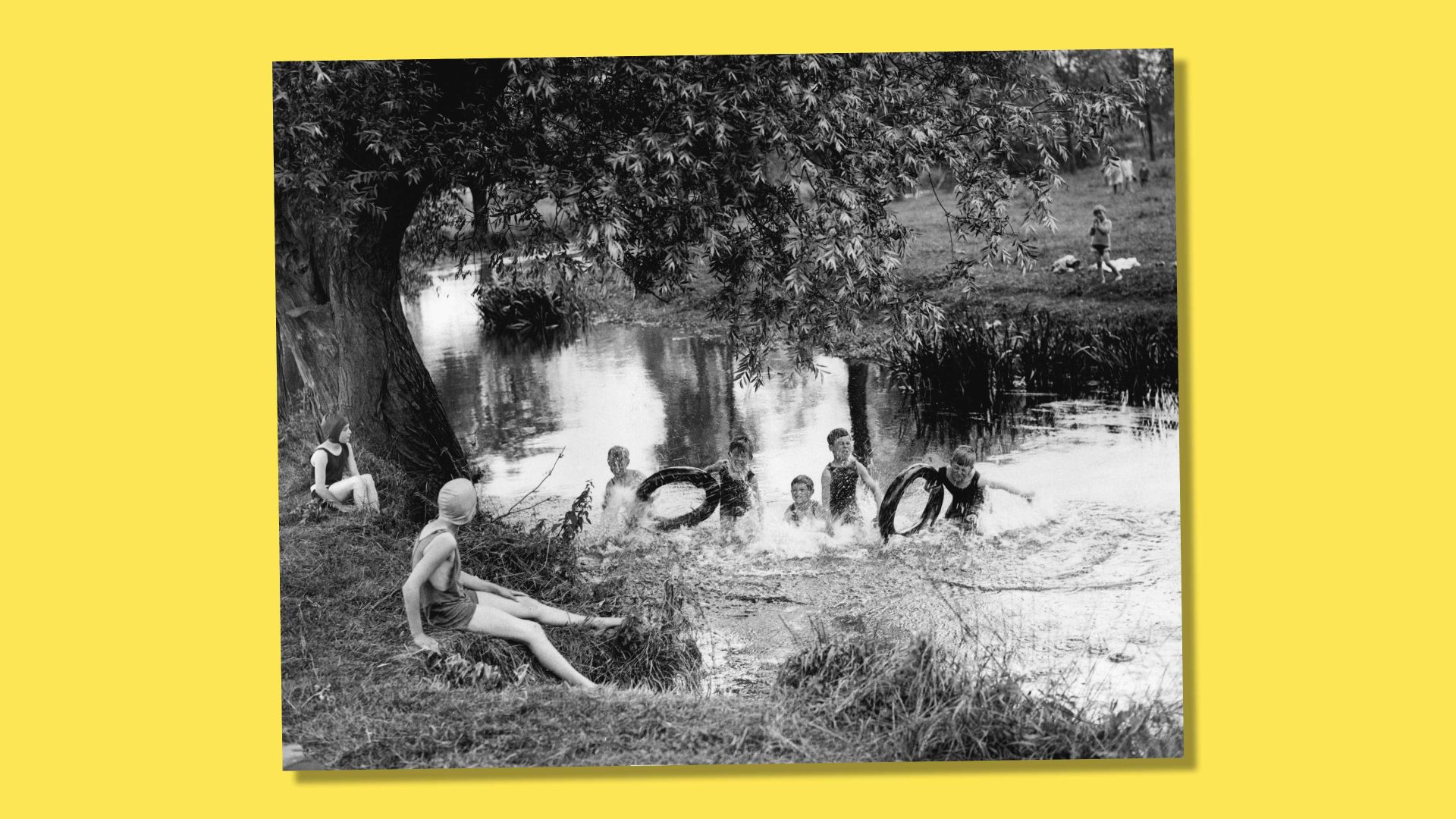

Playford and Lackford, then, were probably both East Anglian villages which in medieval times were the sites of merriment, frivolity and water frolics. We can suppose that, in the relatively low-lying East Anglian landscape, slow-moving shallow streams provided ideal sites for children to splash around and play in safely, whereas in other, hillier parts of the country, shallow fords were not so common.

This supposition is strengthened by another East Anglian ford which was rather certainly used for merrymaking. Glandford in north Norfolk, between Holt and Blakeney, appeared in the Domesday Book as Glamforda, with the first element of the name coming from Old English glēam “merriment”, which survives in Modern English in words such as glee and gleeful. In Glandford the ford, which crosses the River Glaven, was another place where people went to have fun in the water – and, happily, there are still youngsters who do so today.

LEK

The originally Swedish word lek refers to a patch of open ground which is used during the breeding season by males of certain bird species – notably the black grouse and the capercaillie – to “play”, or rather display, as a way of attracting females. The display itself is also called a lek.