Paris is certainly getting the postcard treatment on our screens right now.

Internationally popular Netflix series such as Call My Agent!, Lupin and Emily in Paris have put the spotlight on the city’s finest aspects and, without doubt, it comes out looking lovely and romantic and highly desirable.

Paris is at it again, in Mrs Harris Goes to Paris, which arrives in UK cinemas on the back of a decent US run, where its combination of escapist storyline, old-fashioned values and gorgeous locations and clothes have worked a familiar charm.

Of course, it’s all a lie. Paris is a tough, cold, hard city underneath it all. As writer Edward Chisholm puts it in his current best-selling memoir A Waiter in Paris: “There’s the Paris you see, and the Paris you don’t see.”

But how damaging is it to perpetuate the myth, as Emily in Paris does so prettily, that it’s all glamorous thin women who eat dainty croissants and hot, sexy chefs, fashion shoots and Instagrammable moments on quaint streets?

This fluffy vision has come to be known in French film and TV circles as the “American gaze”. It has become a very profitable one. Apple’s Franklin is there, shooting with Michael Douglas as Benjamin Franklin; Juliette Binoche, John Malkovich and Emily Mortimer are filming The New Look, the story of Christian Dior, Balenciaga, Givenchy and Coco Chanel; Keanu Reeves was in town making John Wick: Chapter 4 and, as of this week, even Woody Allen is back on the Paris streets shooting his 50th feature film, with an entirely French cast.

“It’s OK for all of them,” says Lucas Bravo, who plays the hot, sexy chef Gabriel in Emily in Paris and now works his considerable charms as André the nerdy (but still hot) accountant in Mrs Harris Goes to Paris. “The Americans make their show or film and then they all go home, and we French who are in these shows are left behind to face the wrath of our home audience.”

He recalls shooting a scene on Emily in Paris with his French co-star, Camille Razat, in which both of them were speaking French. “We did the French dialogue, the director shouted ‘Great, cut, let’s move on,’ and everyone started packing up but me and Camille, we were shocked because the acting was bad, the lines badly delivered, like soap opera bad, and we had to beg for another take because ultimately, we would be laughed out of town by anyone who understood French. So, yes, there’s a pressure and responsibility we have to pick ourselves up sometimes.”

Bravo is in London for the Mrs Harris premiere, enjoying a career high after years of waiting tables, during which time he clearly perfected his English, a skill that now stands him in very good stead. But what does he really think of these prettified views of his city, the city in which, we remember, Sartre and

others strove for authenticity?

“Look, from my personal perspective, there’s always a lot of me in my characters, so to me, they’re authentic enough – the other 50%, that’s the movie magic,” he says smoothly.

“But as for Paris, it’s so diverse that it would take many points of view to tell the whole story of it. You have to pick an angle at some point and just because you choose one prism of perception to show Paris, it doesn’t mean you’re insulting all the other areas. There are many ways to interact with Paris but you can’t fit them all in one movie, one perspective – it’s too complicated, too diverse for that and you wouldn’t do any of the areas justice.”

Mrs Harris Goes to Paris is adapted from a story by Paul Gallico, a former sportswriter who went on to pen four books about Mrs ’Arris (Fabian respectfully re-instated the ‘aitch’) and who also wrote The Poseidon Adventure.

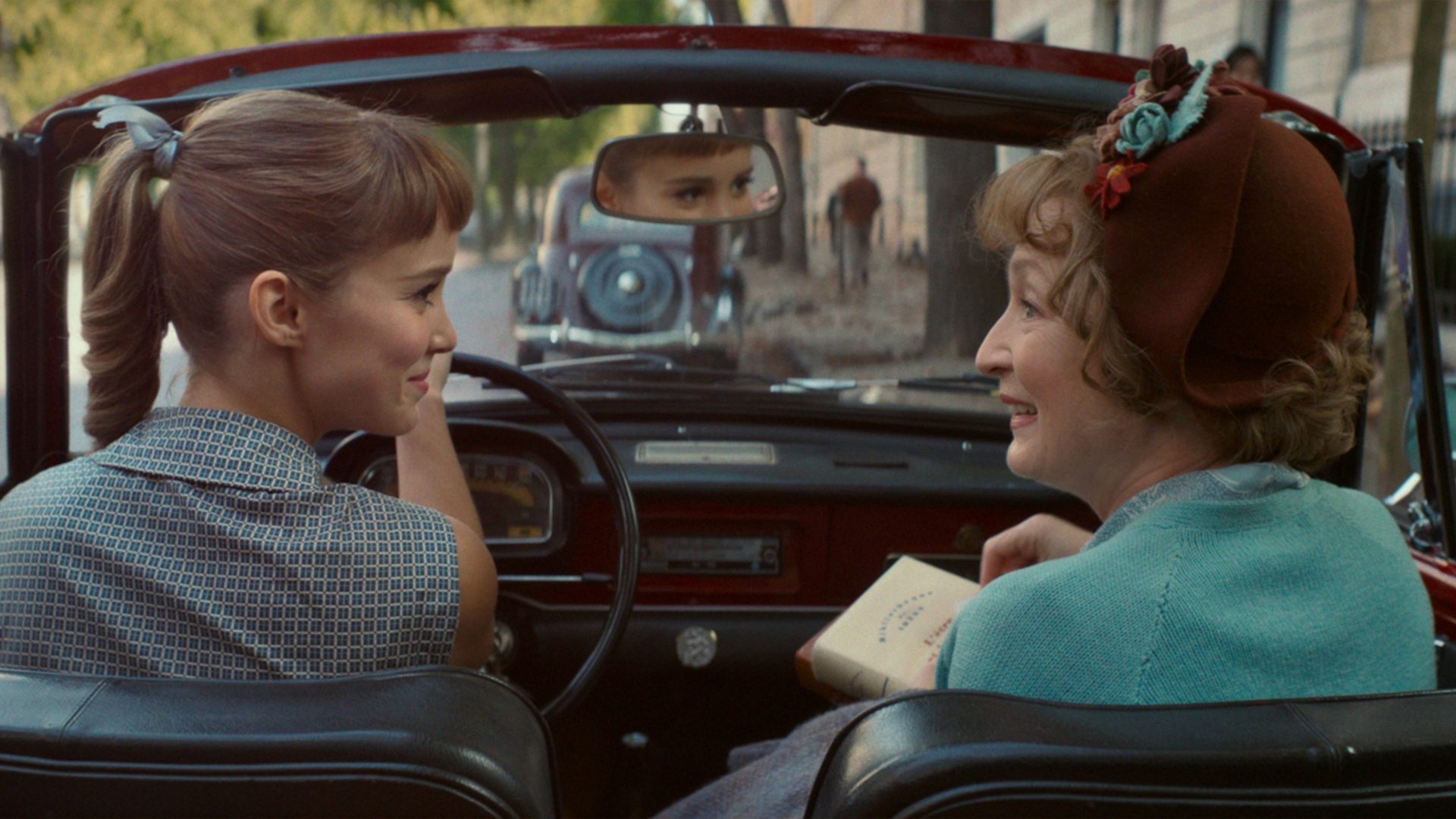

Set in 1958, it is a right charmer. Lesley Manville plays the titular no-nonsense cleaning woman, widowed in the second world war, who, tidying the mansion of her wealthy employer Lady Dant (Anna Chancellor), falls in love with a Dior dress in a cupboard. She decides she must go to Paris and buy one.

Off she teeters, like Cinderella crossed with Paddington Bear, right into the house of Dior, much to the distaste of its snobby gatekeeper Madame Colbert, played by the redoubtable Isabelle Huppert. Much of the film’s success lies in watching these two characters go toe to tiny toe and both actresses deliver winning performances.

But it’s Manville’s disarming Mrs Harris who wins everyone over, including Lucas Bravo’s André, one of the Dior models, Natasha (played by Alba Baptista) and a smitten-seeming Marquis de Chassagne, played by Lambert Wilson, who wines and dines our charlady at the finest Parisian establishments.

It’s utter nonsense, of course, and if it had burst into musical numbers on the Champs-Élysées, across the Pont Neuf and up the Eiffel Tower, it wouldn’t have been a surprise. But Manville on this form could win anyone over, all helped by a lightness of touch from director Anthony Fabian.

“But you see, the key to it working is authenticity,” insists Fabian. “No disrespect to Darren Star and his creation of Emily in Paris, which is an

addictive guilty pleasure but which is ridiculous – you would never for a minute claim it has even one toe in reality. With Mrs Harris, I wanted to walk a tightrope between magic and reality.

“So I insisted that all the French parts are played by French actors and we collaborated with Dior in a very authentic way, using their archive and their vintage dresses, even their iconic oval-backed chairs for the fashion salon. That was what’s essential, because authenticity is Mrs Harris’s secret weapon, it’s her essence, it’s what unmasks all the people around her, so that was the key word of the whole thing, authenticity.”

Even so, Mrs Harris didn’t really go to Paris – she went, for the most part, to Budapest.

“Paris is a nightmare to shoot in, and very expensive, especially if you’re not predominantly French-language, which we aren’t,” reveals Fabian. “Your money goes three times as far in Budapest, which in any case is built on Parisian lines, inspired by the same avenues and has a long history of doubling for Paris. Plus,” he adds with a whisper, “in Hungary, you have highly skilled crews who are hard-working and uncomplaining, which you can’t always say the same about in Paris…”

Fabian shot the door of Dior on Avenue Montaigne in Paris, but the rest was entirely rebuilt in a studio in Budapest, according to the original plans of the Dior building, the salon, the staircase, the seamstress’s atelier. The vintage dresses were transported by road under the care of a supervisor who then oversaw the use of them on set, how they were worn and fitted, with no makeup allowed near the fabrics.

In any case, for Mrs Harris, Paris represents some sort of dreamland. The character, as embodied by Manville, goes through it like a dose of reality, dispensing wisdom and homely expressions such as “I’m such a clumsy clogs,” or “ooh, that’s the ticket,” and making young existential Parisians some of her special “toad in the ’ole”.

As Fabian notes, the cockney “thing” can quickly become overdone and cheesy, but they all just about get away with it in this confection. “It had a very simple pitch from which we never waivered,” he says: ‘Cockney cleaner

falls madly in love with a couture Dior dress and decides she has to have one.’ That set up the dream and the class divide and the journey, and everyone could get on board with it.”

Edward Chisholm’s A Waiter in Paris book presents a contemporary flip side, the story of a young Englishman (known only as l’Anglais) who, down and out in Paris, gets a job in a cut-throat bistro where he must learn to be a waiter if he’s to survive.

The world behind the restaurant’s swing doors is a fascinating demimonde of characters, from drug dealers and Tamil fighters to refugees, African migrants, wannabe actors, Foreign Legionnaires, thieves, snitches, beautiful hostesses, a deposed Count, a weary sommelier… all modern metropolitan life is here, all scrabbling an existence in tough conditions, scraping a way out of poverty away from the view of the tourists, the politicians, the wealthy

regulars and the fashion crowd.

I must admit to skin in the game: I’ve optioned this terrific book and, with the author, am producing the movie of it, one that will portray a very different city to the Paris of Emily and Mrs Harris.

Even in this contemporary snapshot, this lifting of the romantic lid, there’s

always a dream aspect to Paris, even at its harshest and coldest and cruellest.

As Chisholm writes: “Even when you’re broke, exhausted and hungry, there’s an indefinable magic about the place. No matter how much your feet hurt… as you walk up the Avenue de l’Opéra at night or across the Seine under the shadow of Notre-Dame, inside, you can’t help but feel intensely alive. Because you’re in it, you’re in the film, you’ve got a walk-on part… Everything feels possible. When you’re in Paris, you couldn’t care less about anywhere else. Your world shrinks: it’s the centre of the universe. There is nowhere else.”

So A Waiter in Paris is another essence of the city, another prism of perspective – it might not be a fairy tale, but it is another story, another

movie, another Paris. Even if we do end up shooting it in Budapest.

Mrs Harris Goes to Paris is in cinemas now