Humanity is fighting for its survival as religion, inequality and poverty push more people into conflict than at any time in history. Wars rage interminably as technological advances make killing more efficient and peace professionals fail to deliver much more than rhetoric.

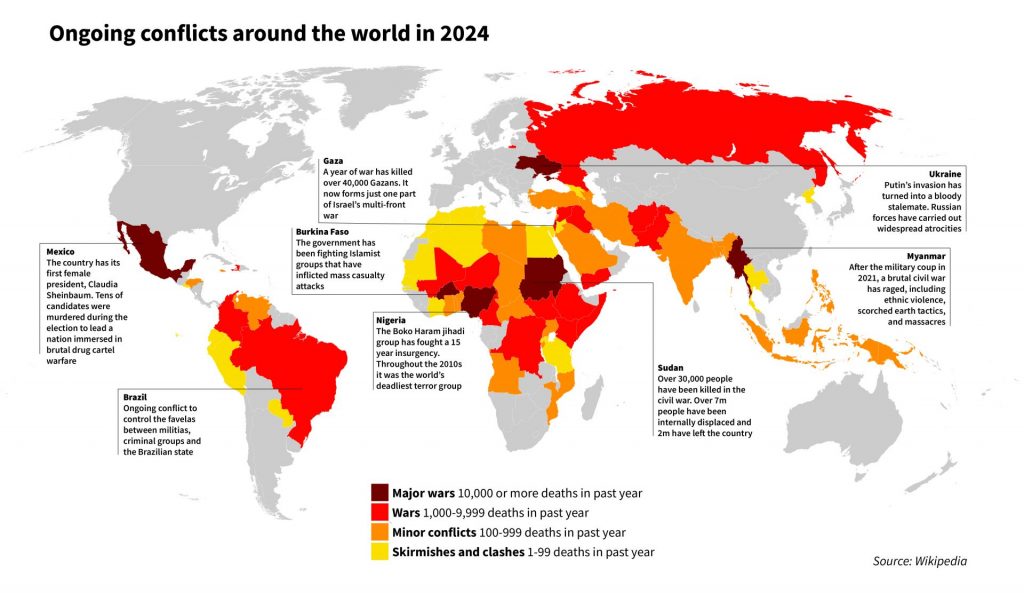

Across the globe, almost 100 countries are currently gripped by conflicts, many of which may never end, according to Steve Killelea, the founder and executive chairman of the Institute for Economics and Peace.

Few of these conflicts will grab headlines like the escalating war in the Middle East or Russia’s grinding war in Ukraine, which have an immediate, ongoing and outsize impact on western geopolitical and economic interests.

Unlike last century, modern wars and conflicts rarely end in military victory or in peace agreements. Each year, more countries slide closer to war, more become militarised, and more face entanglement in conflicts beyond their borders.

Challenges thrown up by climate change – drought; flood; extreme weather; food security; pollution; mass migration; disease; land and ocean degradation; loss of biodiversity; social, political and economic instability – can cause or aggravate conflict conditions.

Organisations like the United Nations and other non-governmental entities employ vast numbers of people at huge cost to taxpayers worldwide, yet they consistently plead for more funding as conflict and human misery grow in lockstep.

Conflict experts generally fall into despair, saying that peace has become a pipedream for ordinary people, while providing a bonanza of opportunities for corporations, governments and authoritarian rulers, who regard it as a source of profits, jobs and power. As the rewards rise, for shareholders and politicians alike, so conflict expands in a cynical doom loop.

“This is an existential crisis for humanity,” said Killelea, whose Sydney-based organisation monitors conflict worldwide and publishes an annual “global peace index” using specific regional data to calculate the likelihood of conflicts expanding.

The reports are dense as the information is cross-referenced and categorised from detailed breakdowns of violent events – battles, protests, riots, strategic developments, violence against civilians.

“Last year, there were more conflicts than at any time since the end of the second world war. There were 56 at the end of the year (2023), and that was up to 59 last time I counted,” said Killelea.

“There are 92 countries involved in conflicts beyond their border. That’s the most since the inception of the Global Peace Index 18 years ago,” he said. In 2023, 97 countries recorded a “deterioration in peace,” according to IEP analysis, and 104 recorded a “deterioration on militarisation”. Again, Killelea said, that’s more than at any time since he launched the annual index report.

In some parts of the world, insurgencies have been rumbling along for decades, largely contained geographically and barely registering as news outside the country or region.

The war in Ukraine, which dates to Moscow’s 2014 annexation of Crimea before intensifying in 2022, overshadows other long-simmering tensions in Europe, some of which, inevitably, bear Russia’s footprint.

Moscow has supported the de facto independence of South Ossetia and Abkhazia, which broke away from Georgia after its war with Russia in 2008. These tensions serve a similar destabilising role for Moscow as its support for Transnistria, the breakaway region of Moldova. With Russian support it declared independence in 1990, but the Moldovan government does not accept that status.

Serbia’s refusal to recognise its former province of Kosovo as an independent state leads to occasional border flare-ups. Bosnia and Herzegovina is troubled by ethnic divisions between Bozniaks, Croats and Serbs.

Greece and Turkey, both Nato members, are yet to resolve their dispute over Cyprus, which has been divided since Turkey’s 1974 invasion. Though war has seemed less likely with the passage of time, the issue simmers nevertheless, amid friction over territorial boundaries and access to natural resources in the eastern Mediterranean.

Similarly, in south-east Asia, the governments of Myanmar, Thailand and the Philippines face relatively low-key, anti-state or extremist conflicts that barely register outside their borders.

Since gaining independence from Britain in 1948 and changing its name from Burma, Myanmar has endured military rule, sectarian and ethnic conflict, genocide, and since a military coup in 2021, intense political, economic and social instability.

Armed ethnic groups, the Karen, Kachin and Shan have fought for autonomy from the state for decades. The violent expulsion by the military of hundreds of thousands of Muslim Rohingas to neighbouring Bangladesh in 2017 caused a shocking humanitarian crisis that led to widespread condemnation of the Myanmar government.

The Abu Sayyaf group in the southern Philippines is believed to have taken its name in honour of an Afghan politician called Abdulrab Rasul Sayyaf, an Islamist, mujahideen and al-Qaida acolyte, reflecting its own extreme ambitions. It was founded in the early 1990s by Abdurajak Janjalani, a Filipino Muslim who fought in Afghanistan against the Soviet Union’s occupying forces.

Abu Sayyaf’s initial goal of setting up an independent Islamic state on southern islands dissipated to criminal activities like kidnappings, with captives often beheaded if ransoms were unpaid. It stands out from other militant Muslim groups in the Philippines for committing one of the worst marine terrorist attacks, in 2004, bombing a ferry and killing around 100 people.

Efforts to counter terrorist activities in the Philippines have involved Malaysia and Indonesia, as well as support from the United States.

In Thailand’s south, fighting between state forces and a number of fractious Muslim groups has caused thousands of deaths. Militants want autonomy or independence from the Buddhist state, and efforts to negotiate a ceasefire, mediated by neighbouring Malaysia, have been punctuated in recent years by attacks that have killed more than 7,000 people.

Kabul: Photo: Wakil Kohsar

India is home to the world’s longest-running insurgency, with Maoist militants called Naxalites fighting the state for economic rights since 1967. Up to 15,000 people, including civilians, are estimated to have been killed in fighting between the rebels and the state.

In Pakistan, simmering discontent in isolated, gas-rich Balochistan state has developed into anti-state violence as militants fight for autonomy, and economic access to natural resources. Tensions are exacerbated by the presence of Chinese government corporations as part of Beijing’s troubled Belt and Road Initiative global infrastructure outreach project. Over the border in Iran, Baloch groups are fighting for independence from the repressive Shia state.

Pakistan is also increasingly blighted by the re-emergence of Islamic extremism more than a decade after its mountainous tribal regions were largely rid of terrorism in a lengthy military operation. The Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan, or TTP, an offshoot of the al-Qaida-linked Taliban now controlling Afghanistan, has returned to terrorising local communities in what is fast developing into an existential threat to the Pakistani state.

The Taliban’s return to power in Afghanistan, after a retreat deal brokered in 2020 by former president Trump, has emboldened extreme-Islamist and terrorist groups across the globe, including Hamas, Hezbollah and the Houtis, all of which are fighting Israel with Iran’s support.

The Taliban are providing safe haven for almost two dozen jihadist groups, according to the UN Security Council’s Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team, each with its own extremist agenda for the overthrow of governments in China, Iran, Russia and its central Asian satellites, as well as the United States and the west generally.

The common denominator for much of the conflict is al-Qaida, the group responsible for the 9/11 attacks of 2001 when it was led by Osama bin Laden and based in Afghanistan. It was supported by the Taliban’s first regime, and many of the figures from that time, who are sanctioned by the UN Security Council as terrorists, are back in power today.

Until recently said by the United States to have been degraded to the point of irrelevance, al-Qaida has reconstituted in Afghanistan, where it is embedded in the administration. It also runs training camps for militants and funnels cash and weapons to affiliates in south Asia, the Middle East and Africa, likely using the Taliban’s well-honed heroin and methamphetamine trafficking routes.

Like “little brother” Taliban, it is closely aligned ideologically with Hamas, Hezbollah, and other anti-west and anti-Israel groups. The Islamic State group, which grew out of al-Qaida, remains active in the Middle East, and its Afghanistan affiliate, IS-Khorasan Province (IS-KP), is seeding cells across Europe, as arrests in recent years show.

One of al-Qaida’s main arenas is Africa, which offers a multitude of opportunities for conflict expansion in the economic weakness and social instability of post-colonial nations.

Affiliates are active in Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Mali, Niger, Burkina Faso, Somalia and Kenya. In many of these places, and in south Asia, al-Qaida is rivalled by Islamic State, though the al-Qaida/Taliban-affiliated Haqqani Network is believed by some experts to be behind some attacks claimed by IS-KP.

Killelea notes the growing risk of conflict in Ghana, where its status as one of Africa’s most peaceful countries is threatened by internal issues and conflict spillover from neighbours. Cameroon’s crackdown on Anglophone communities has led to thousands of deaths and the rise of separatist groups. Peace in Ethiopia is fragile, following the war in Tigray, as ethnic tensions in other regions lead to internal conflict, and relations with Eritrea and Somalia threaten to escalate.

Greg Mills, who heads the Johannesburg-based Brenthurst Foundation, and is a senior fellow of the Royal United Services Institute in London, said the vulnerability to conflict and violence of African nations was built into the colonial model for state creation and was compounded by independence.

Borders were arbitrarily drawn “based on European, external interests,” he said. “African states after independence never had to extend power to their extremes, which was the determination of state formation, for instance in Europe. The borders themselves became the determination of the shape of the state, not the systems of authority and control, including taxation, within them.”

Consequently, African states were weak from birth, said Mills, who has authored, with fellow security expert David Kilcullen, a new book called The Art of War and Peace: Understanding our Choices in a World at War.

The built-in weakness of African states “was compounded by several postcolonial developments, including the rise of authoritarianism, the pursuit of external interests, and the maintenance of largely colonial systems of economy, where an external elite was simply supplanted by indigenous ones,” he said.

Experts said that ceasefires rarely lead to enduring peace, as the basic condition – that all sides see more to be gained from peace than from war – rarely exists.

Killelea’s figures show that peace has become measurably elusive over the past 50 years. In the 1970s, he said, “49% of all conflicts finished with a military victory for the government or the rebels; that had dropped to 9% in the 2010s.” Peace agreements, he said, “dropped from 23% in the 1970s to 4% in the 2010s”.

“If a peace process is only to allow enough time to recover between bouts of conflict, for one party or another to exit from the conflict, or as a means of legal or diplomatic subterfuge, or if one party or another still is more interested in war than peace, then war will likely resume,” Mills said.

“For conflicts to end peacefully, there is usually a need for equal pressure on the belligerent parties, from the outside, to get them to the negotiating table,” he said. And once there, opponents need a clear methodology for making peace, a sense of timing, and leadership, which he said is critical but often elusive, notably in “the endless wars of the Middle East”.

Half of all countries that end a civil war are likely to fall back into conflict soon after reaching agreement to end hostilities.

Peace is stymied by vested interests, as well as a lack of will and capacity among the governments and organisations that purport to have expertise in conflict resolution, says Frank Ledwidge, a barrister and academic who served in the military in the Balkans, Iraq and Afghanistan, and author of Losing Small Wars. “Having people who have the vaguest clue about the countries they’re working in might help, but it is certainly never seen as a priority,” he said.

The global political structures of the 20th century, such as those of the postwar liberal order, the cold war and the neoliberal globalist boom of the 1990s now seem a distant memory. That scaffolding was kicked away by the fall of the Berlin Wall, 9/11, the wars on terror, the financial crisis and the rise of authoritarianism. What emerged to take its place is a cycle of cynicism, violence and despair.

“Ultimately,” said Ledwidge, “peace doesn’t pay.”

Lynne O’Donnell is a columnist at Foreign Policy. She was the Afghanistan bureau chief for Agence France-Presse and the Associated Press 2009-2017