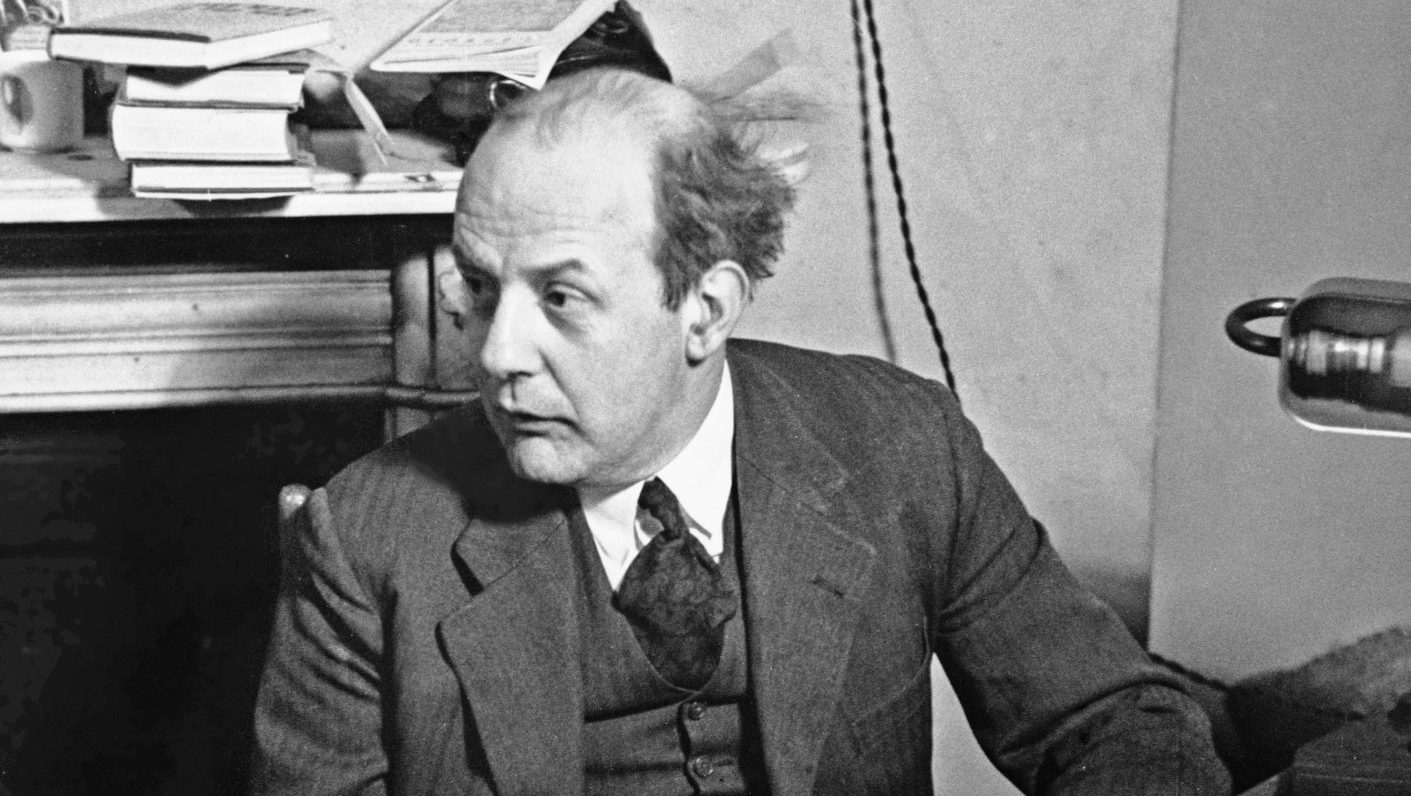

Life without memory is no life at all,” wrote Luis Buñuel. “Our memory is our coherence, our reason, our feeling, even our action. Without it, we are

nothing.”

Buñuel wrote this in his late 70s as, just like his mother before him, he began to lose his own. For the Spanish surrealist filmmaker, this was a source of regret, but also an opportunity. Imaginations, dreams and false stories began to crowd in, half-truths turning into truths until the faultlines in his

storytelling were unnoticeable. He was becoming a living embodiment of his

films.

In his last days, while drinking his favourite martini (dry gin, a few drops of Noilly Prat through which one ray of sunlight had passed, half a spoon of Angostura bitters poured over ice) he attempted to piece together the fragments. Could he remember if he really, scandalously, had the hobo in 1961’s Viridiana lift her skirts and expose herself to the dinner guests lined up expecting her to take a group photographic portrait? Since he rarely watched his old films he couldn’t have been absolutely sure, could he?

Now, with YouTube there for the instant verification of the idly curious, one could possibly check. But perhaps, like Buñuel, it’s best not to. To let scenes flash through the brain now and then like filmic shooting stars.

I do know Viridiana is a masterpiece. My own memory assures me it is. It was the first film of his I watched, almost by accident, when I was 16, and I’m considerably older now. Then I had little idea how radical Buñuel was or, more properly, how mischievous. I was not to know that this film had been banned by Franco for 15 years and that the scene that mesmerised me was a blasphemous takedown of The Last Supper. It was a black and white antidote to primary-coloured, reverent Da Vinci, populated by the damaged and the hopeless – rather than the soon-to-be saintly – that outraged the clergy.

All eras should have a Luis Buñuel. It’s doubtful we have one today. His rap sheet is long: films banned, exile, ostracism, damnation by popes, attacked by fascists and cinemas stormed when his second surrealist masterpiece, L’Age d’Or, made with Salvador Dalí (a mere bit player despite his self-aggrandised version of the tale) made its Parisian debut.

At the heart of Buñuel, his surrealism, anarchism, and brilliance, is an affectionate devilry (literally, said some) that he never lost from his school days in dry, dusty red-neck Aragón.

But this wasn’t tiresome childishness. Buñuel put it to the service of the challenge. Joining the ranks of André Breton’s surrealists was the perfect place for this. For Buñuel, the targets were interwar Spain and its drift into a Catholic-fused fascism that grew from the stony soil of a conformist, dull religious-rigid society. Rumbustious boys like him would never be content with a life like that. Buñuel would warmly embrace atheism thereafter.

And that buttoned-up society meant the glimpse of a woman’s ankle or sway of her hips took on the equivalent of arriving in Nirvana. Like Fellini, Buñuel had a fascination/fetish/fear for women all his life. In all his films they remain unfathomable. See Catherine Deneuve’s mask-like beauty in any film he made with her. Try Belle de Jour or Tristana.

In Viridiana, made late in his career in 1960, it is Mexican actress Silvia Pinal’s turn to play the unreachable. She is the title character, a trainee nun visiting her rich uncle one last time before she takes Orders and he dies. Her uncle is entranced by her, realising she looks identical to his dead wife. In one scene he asks Viridiana to wear his wife’s wedding dress, telling her she died on their wedding day. You can almost hear Buñuel chuckling to himself as priests everywhere suffer the vapours.

It is a shocking and daring film, even looked at from here. It is also beautifully staged, with a rapier-sharp thrust at the midriff of a bourgeois society that insists on maintaining the illusion of striving for impossible, even undesirable, standards at the risk of damnation for failure. The beggars banquet tableau is exquisite. After her uncle dies and she inherits his country house, Viridiana, her former vocation to the fore, invites the local paupers in to feed and morally educate them. They repay her with an orgiastic display of bacchanalian excess. This scene, at the heart of the film, sweeps the watcher along with its anarchy, its failure to accept the rules of redemption, its defiance of happy endings. It is pure Buñuel.

And pure Buñuel is subversion in all its guises. Viridiana was one of his classics from his late-flowering career in the 1960s. He was a prolific moviemaker, sometimes churning out three a year during the many periods he was exiled politically and geographically. He made 13 films in Mexico during that country’s purple patch in the 1940s, and lived there for the rest of his life, apart from periods filming in Spain and France. There were short unhappy spells in Hollywood, and briefly in New York at the Museum of Modern Art.

But, despite the Mexican years, Buñuel remains a European filmmaker forged in tumultuous times, particularly in his home country, when art and politics were a matter of life and death. A time when the kicking back against stultifying norms and mores, the questioning of religion and social class, especially in backwaters like Aragón, were likely to be met with violent reactions. Even the rapidly expanding moviemaking industry of the 1920 and 30s could not dodge the febrile politics of the time.

You were either republican, communist, anarchist, atheist, devout or fascist. It was impossible to be none of these. Buñuel was all four of the former at various times with various degrees of passion and cynicism. “Still an Atheist… thank God!” is one chapter in his sparkling non-autobiography, My Last Breath.

And of course, it was the Spanish civil war that forged the identities of many like Buñuel. The delight of the throwing off of the shackles of repression and the hope of the Second Spanish Republic gave way to the advance of the Falangists and Franco, armed conflict in the streets of Madrid, where Buñuel was studying, and the splintering of the left into a myriad of competing, self-defeating factions. An anarchic filmmaker he may have been, but the anarchists clustering around the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo nauseated him with their brutality and dogma. The murder in 1936 by nationalists of his dear friend, the poet Federico García Lorca (“he was his own masterpiece”) haunted him until his own death. While working and filming in Paris, he remained angry for the rest of his life that the French government had not come to the rescue of the Republic nor even supplied it with arms as Franco advanced.

Of course, no appraisal of his work can ignore Un Chien Andalou made in 1929, with its still-shocking razoring of a woman’s eyeball, and its anti-religion companion L’Age d’Or a year later. These short films still astound today; their power seems extraterrestrial even in 2023. It’s perhaps no wonder that cinema screens were ripped, priests fainted, protests were held or people simply fled the cinemas in which they were shown. In those two

films, Buñuel, with the eventual Franco sympathiser Dalí riding his coattails, invented surrealist cinema. In My Last Breath he explains: “Our only rule was very simple: no idea or image that might lend itself to a rational explanation of any kind would be accepted. We had to open all doors to the irrational and keep only those images that surprised us, without trying to explain why.”

That subversion of the rules stayed with Buñuel for life, whether he was examining attitudes to God, politics, class, morals, sex, art in his films. His takedowns of the existing order are all the more incisive because his surrealism forces us to double-take, heaven forbid, to have to think. And of course, most of his films are busy with distracting tickling under the chin while the knife enters between the shoulder blades.

Luis Buñuel Portolés died aged 83 in Mexico City in July 1983. And 40 years on, boy are we missing him. It is hard to think of any filmmaker quite like

him today. A citizen of nowhere and everywhere, he remained a boy from the backwater who dismissed in words and moving images the petty bourgeois, the faithful and the nationalist. He was a lifelong hater of Franco while many of his countrymen came to an accommodation.

He was handy with his fists (he was an amateur heavyweight boxer in his

Aragón days and many times thought of inflicting his skills on Dalí) but his

anti-establishment credentials did not prevent him from making the perfect

martini in the most salubrious of Parisian settings, or holding court in one of the city’s restaurants. He is, then, contradictory, and therefore a perfect guide to help us understand the Europe of the early and middle 20th century.

It is intriguing to wonder what he would have made of the Europe of today. It is perhaps not polemic that we need to expose the muddled thinking, the lust for simplistic solutions, the return of nationalism, but a Buñuelian disruption of the narrative, a skewering of perception and a new way of seeing.

On the 40th anniversary of his death, and returning to the master’s words at the beginning of this piece, we should not let Buñuel’s cinematic memories fade, or his reminder of the life-changing potential of film be forgotten. July would be a great time for a celebration of his work and a re-examination of what it tells us about ourselves. Buñuel the atheist would not have given a damn about any of that. But we should do it anyway.

Michael Gilson is the former editor of, among others, the Scotsman and Belfast Telegraph. He is a lecturer in journalism and a published author. His book on the history of the British suburban garden is out later this year

WHAT THEY SAID ABOUT THE BEST OF BUÑUEL

1929 UN CHIEN ANDALOU

“A mysterious, free-associating accumulation of images of violence, beauty and absurdity that confounded those who saw it then and confounds still” Phillippa Hawker, The Age (Australia)

1930 L’AGE D’OR

“Nonsensical, erotic, scandalous, revolutionary: Luis Buñuel’s surrealist masterpiece is not for those of a nervous disposition” Jamie Russell, BBC

1950 LOS OLVIDADOS

“This is a cold and ruthless film as impersonal as a surgeon’s knife… The

direction of Luis Buñuel leaves you almost numb with its chilly message of harsh futility” Milton Shulman, Liverpool Echo

1961 VIRIDIANA

“An uncompromising film, as brutal in its message as it is baroque in its cinematography… it is much to have anything at all to say in the movies; it is more to say it as powerfully as Buñuel does” Dwight Macdonald, Esquire

1967 BELLE DE JOUR

“Possibly the best-known erotic film of modern times, perhaps the best. That’s because it understands eroticism from the inside-out – understands how it exists not in sweat and skin, but in the imagination” Roger Ebert, Chicago Sun-Times

1970 TRISTANA

“Tristana may look like an aesthetically conservative film. Don’t be deceived. It makes its effects by the very austerity of its style. And its effects are diabolically ironic” Dilys Powell, Sunday Times

1972 THE DISCREET CHARM OF THE BOURGEOISIE

“Bunuel’s art is as insolent as ever… a deeply funny movie, as a viewing experience it’s like walking across a perilous, swaying little bridge whose guide rails are periodically snatched away” David Denby, The Atlantic

1974 THE PHANTOM OF LIBERTY

“The physical production is stunning to look at. The cast is large, first-rate, but the presence that dazzles us is that of the Old Master, just off screen, mercilessly testing our senses of sanity and humour” Vincent Canby, New York Times

1978 THAT OBSCURE OBJECT OF DESIRE

“Filled with small, droll touches, with tiny peculiarities of behaviour, with moral anarchy, with a cynicism about human nature that somehow seems, in his hands, almost cheerful” Roger Ebert, Chicago Sun-Times