One autumn day in 2013, just a few months before Vladimir Putin annexed Crimea, I was on my knees in the mud searching for the remains of Russian soldiers. Next to me, Marianna was poking the ground with a small spade, while her friend Olga walked through the pine forest with a metal detector. At times it beeped furiously; the older trees were still riddled with bullets and shrapnel.

Marianna has a maternity-clothes business, and Olga is a journalist, but they were part of a group of volunteer diggers called Razvedka, or “exploration”. To my surprise, they had chosen to spend their holidays camping in the woods, looking for the bodies of Red Army troops killed in the second world war.

“Every spring, summer and autumn I get this strange sort of yearning inside me to go and look for the soldiers,” Marianna told me. “My heart pulls me to do this work.”

I was sceptical that much would be found during my short visit, but straight after breakfast, Olga stumbled over what she thought was a tree root – it was a human bone, sticking out of the ground. Later, a teenage volunteer proudly showed off a nearly intact rib cage he had found under a thin layer of leaves and soil. The whole area is still littered with skulls, bones, soldiers’ helmets, ammunition and rotting fragments of leather.

We were in Lyuban, south-east of St Petersburg, where, according to the historian Sinclair McKay, a four-month battle ended in April 1942 in “blood-soaked humiliation for the Soviets”. It was a desperate attempt to break the Wehrmacht’s grip on Leningrad (as St Petersburg was then called) but the Red Army lacked proper artillery support against German lines.

By April 1942, the Soviet force of 327,700 combatants had been all but wiped out and 1.5 million people were still in the city, cut off from the outside world. McKay’s new history of Russia’s second city focuses on the 872-day siege of Leningrad, the city founded by Peter the Great and given Lenin’s name after his death in 1924.

Unlike Paris or Prague, the Nazis were not interested in parading through the city’s streets and squares in their dress uniforms – they wanted instead to wipe it off the map. Hitler saw the 18th-century tsar’s famous “window on the west” as a “poisonous nest spewing Asiatic venom into the Baltic”. He insisted that the city built on the marshes around the River Neva “must vanish from the earth’s surface”.

The siege plan was discussed at a Berlin conference a month before the invasion of the Soviet Union. In his diary, Joseph Goebbels noted that the Führer aimed to prevent German casualties by avoiding a direct military assault on the city, opting instead to “starve it into submission”.

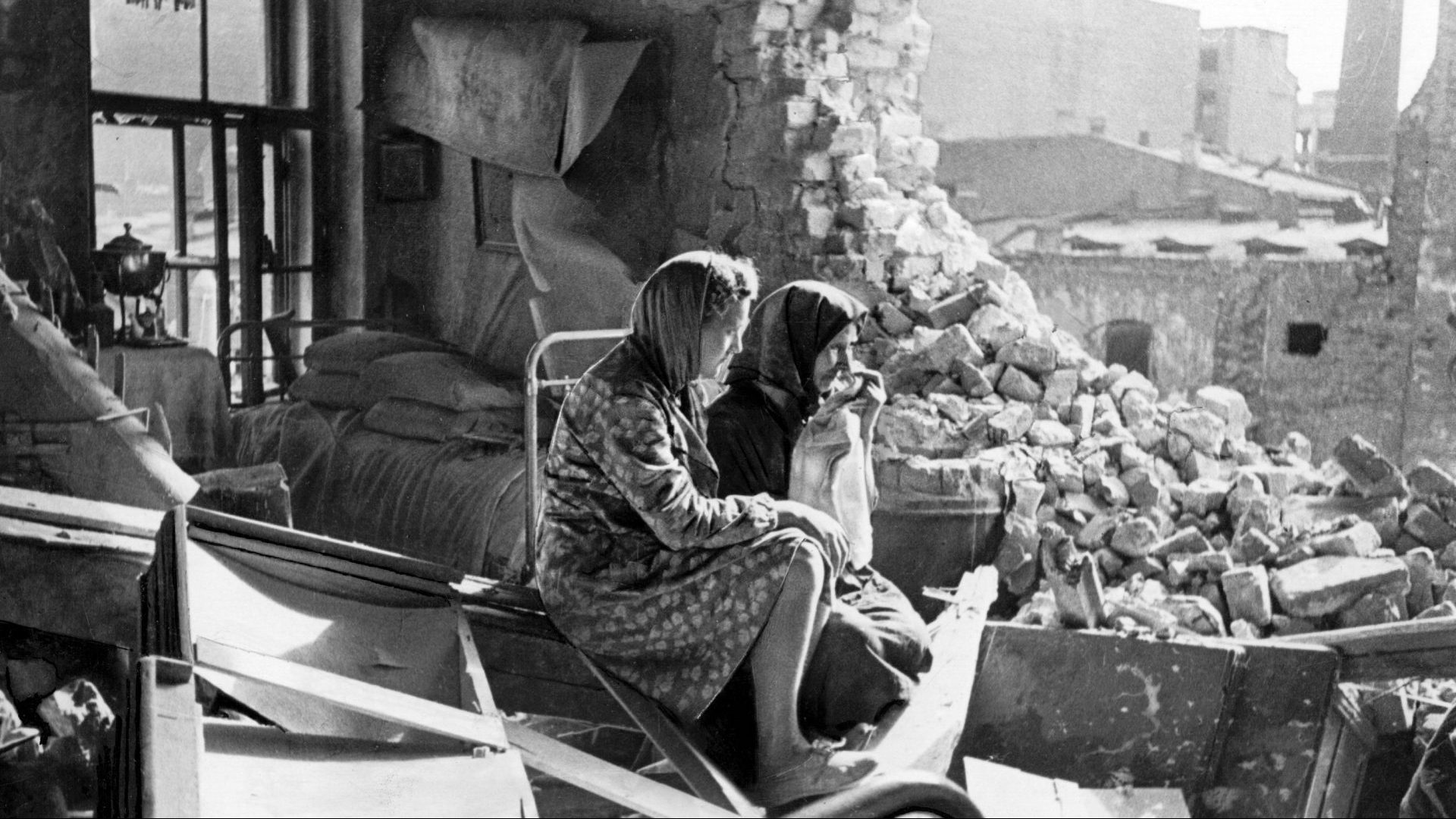

For some Leningraders, death came from the air long before they began boiling leather belts or eating wallpaper paste. It is unnerving to read about the Luftwaffe’s attacks today. Images of bombs gouging craters into the ground at a packed railway station as frantic parents scramble to get their children on to trains recall Russia’s ongoing savagery in Ukraine. The description of lives turned inside out, of homes dissected by bombs so that “everything from toys to lamps to pillows, to old books to slippers and favourite coats” are exposed to the freezing night air, sounds all too familiar.

Russian generals emulated the Nazis during the 85-day siege of Mariupol in early 2022. Submitting evidence to the International Criminal Court in the Hague, human rights lawyers working with the Ukrainian government denounced the “crime of starvation as a calculated warring strategy”.

In the Soviet era, Leningraders under siege were portrayed as people who remained resolute in the face of adversity, standing firm against evil. The Boston historian Alexis Peri provided a far more nuanced picture when she published extracts from 125 unpublished diaries that had lain for decades in Russian archives. Her groundbreaking history, The War Within, published in 2016 revealed the inner turmoil of ordinary people trying to stay alive, retain their humanity and make sense of their fate.Drawing on some of these first-hand accounts, McKay also powerfully conveys the mass torture that killed 40% of the city’s pre-war population.

One of the most heart-rending is the diary of a teenager, Yura Riabinkin, who sought solace in Pushkin and The Three Musketeers. He suffered agonies of remorse for eating a handful of cocoa powder without sharing it with his mother and sister. The boy later died alone in the family apartment, too emaciated to move when the chance to escape finally came.

Meanwhile, an accountant at one of Leningrad’s theatres was overheard complaining that the city’s Communist Party boss, Andrei Zhdanov, started each day “being served cocoa in bed”. A Stalin favourite, Zhdanov remained plump and ruddy-faced throughout while his citizens were eating rats, cats and dogs and occasionally each other.

Colleagues of a machine operator at the Bolshevik Plant opened his locker to find it contained “the remains of a human leg, carefully wrapped in cloth”. The worker confessed he had taken it from an unburied body at the Serafimovskoye Cemetery.

Few dead got a dignified burial. During the first winter of the siege, temperatures plunged to minus 40C. People were too weakened by hunger to waste energy digging graves.

Yet the cold helped in one respect. An ice road was built across nearby Lake Ladoga, Europe’s largest freshwater lake, providing a slender lifeline to the city. At first, horses pulling sleds brought in sacks of flour, then the Red Army began sending trucks. But the journey was fraught with danger. German bombs made holes in the ice and drivers could hardly see their way through the blizzards of snow.

So the authorities posted around 300 women known as “white angels”, equipped with flashlights and red flags, along the route. The women, dressed in white, took shelter in a series of igloos furnished with small stoves. It was, as McKay writes, a “uniquely vulnerable” job requiring physical endurance and “nerves like taut cabling”.

He quotes one of them, Dora Fagina, who witnessed nightmarish scenes of trucks coming under fire and falling through the ice. Food and weapons were brought in, while women and children were driven out, but not all of them made it safely to the other side.

A key strength of this book is its detailed lead-up to the second world war, providing valuable context for the siege. It is little wonder that no relief came from the north.

In the winter war of 1939, when Stalin invaded Finland, his foreign minister, Vyacheslav Molotov, cynically told the outside world that his air force was dropping not bombs but food parcels on Helsinki. In response the Finnish army lobbed bottles filled with tar and petrol at Soviet tanks to devastating effect, and called them Molotov cocktails – the “perfect drink” to accompany Molotov’s generous dinner gift.

A few years later, the Finnish army fought alongside the Wehrmacht, determined to regain its lost territory in Karelia. It blocked supplies to Leningrad, attacked vehicles and ships crossing Lake Ladoga and even taunted the city’s starving inhabitants by shouting out “Russ, Russ, give us some bread! Give us some bread!”

Lack of food corroded relationships. “Loving families,” writes McKay, were “staring at one another with a hatred that could not be contained.” Every home was filled with “souring suspicions that tiny quantities of food – a hoarded sliver of chocolate here, a tiny strip of ham there – had been stolen and eaten. There were mothers looking at their small children with fury.”

Women are hardly sentimentalised in the book, but they often emerge as heroic, whether they were cleaners or ballerinas. When the Germans cut off water supplies, Leningrad became an open sewer. Before the spring thaw, gangs of women wielding crowbars attacked huge frozen piles of human waste in the streets.

On the stage of the Philharmonic Hall, the ballerina Vera Kostrovitskaya had to lead her enfeebled male counterpart by the arms to make it look as if he was dancing when he could barely stand up.

Vladimir Putin would have had an older brother had it not been for the siege. Viktor Putin was only a toddler when he died of starvation and diphtheria in the spring of 1942. His mother, Maria, a factory worker, fainted near a pile of corpses and woke up just in time to avoid being carted away on a sledge to a mass grave. Vladimir himself was born a decade later into a city that still felt like a necropolis.

Considering the atrocious suffering Putin is now inflicting on millions of Ukrainians, “it is impossible not to wonder how much his own mental landscape has been formed, or perhaps malformed, by the generational repercussions of trauma,” writes McKay.

Leningraders who survived the siege are called blokadniki and are encouraged to wear their past ordeal with pride, like a military medal. But some do not want to play the part assigned to them by the regime.

On February 24, as she marked the third anniversary of Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, 83-year-old Lyudmila Vasilyeva staged a rare protest on St Petersburg’s main shopping street, Nevsky Prospekt. Wearing a bright red coat, she held up a sign that read: “People, let’s stop the war! We’re responsible for peace on planet Earth.”

When police tried to detain the octogenarian, she was having none of it. She told them her mother had donated blood during the siege to be eligible for additional rations and that many people in her family perished. “Is this what they died for?”, she yelled in a quavering voice. “So we could go to war again?”

Saint Petersburg: Sacrifice and Redemption in the City That Defied Hitler by Sinclair McKay is published by Penguin

Lucy Ash is author of The Baton and The Cross – Russia’s Church From Pagans to Putin