In the narrow passageway between the main road and the courtyard of the apartment block at Hauptstraβe 155, Berlin, someone has spray-painted, in dripping black, “BOWIE WAS HERE”. And he was.

It was a long time ago now – back in 1976, in fact. In his Thin White Duke phase, Bowie spent two years in this unassuming apartment block escaping his life in Los Angeles, which had become a suffocating cycle of cocaine addiction, causing physical and mental exhaustion.

The anonymous streets of Berlin gave him exactly what he needed. Time to sit around in cafes creating new music. Time to visit art galleries and nightclubs. Time in the Hansa Studios situated near the Berlin Wall, which drew Bowie’s gaze while writing his songs. The same wall that, after his death, Bowie would be credited with helping to bring down. Berlin is full of Bowie phantoms, they are everywhere.

Usually where you have phantoms, you have pilgrims, and Bowie’s apartment in Berlin is no exception. On a grey day earlier this year, people had left flowers propped against the front door, red roses, purple tulips, intimate messages. Even a virtual visit on Google Street View reveals people standing in front of the building taking photographs.

When preparing for his new book, David Bowie: Mixing Memory & Desire, the photographer Kevin Cummins visited Berlin, mainly to get a feel for what it must have been like for Bowie to walk those streets, to gain a sense of him coming home in the evening and opening the large, ornate, glass-fronted doors to his otherwise ordinary apartment, walking across the tessellated brown-tiled foyer and up one flight with its carved wooden railing to enter the door on the right at the top of the staircase.

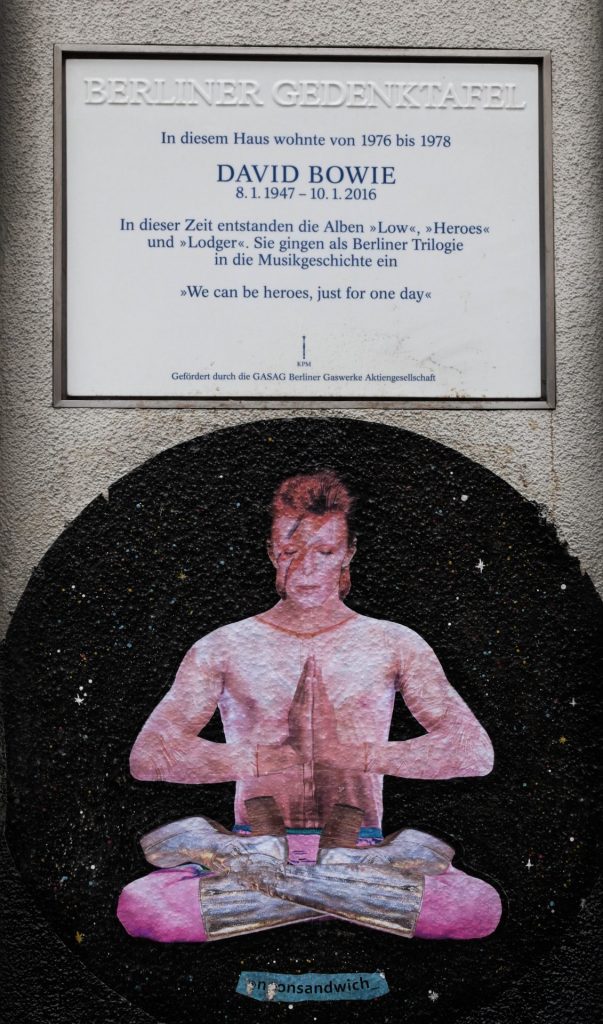

Cummins’s book tells a parallel story of Bowie’s cultural significance alongside his own coming of age, first as a fan and then as a photographer. The Mancunian, probably best known for his images of Joy Division, New Order, the Smiths, Happy Mondays and the Stone Roses, credits his career being inspired in part by seeing Bowie in concert (Leeds, 1973) and capturing a now well-known image held in the V&A of Bowie, arms outstretched, looking ready for flight from the stage. Cummins understood the significance of Berlin for Bowie, not least it being the city that inspired three albums, Low, Heroes, and Lodger (commonly known as the Berlin Trilogy).

Potsdamer Platz, as

namechecked in Where

Are We Now?

plaque from the city of

Berlin outside Bowie’s

former home

Although Cummins never photographed him in the city, he wanted to reflect the feel of it in his book. The yellow of the cover is what he refers to as “the colour of Berlin” – the colour of every U-Bahn station and train. The same colour is washed through the endpapers, with a slightly solarised, slightly exaggerated architectural shot of the Potsdamer Platz street sign. “He was there. I wasn’t,” said Cummins, “but I wanted to locate him in the city.”

It did not seem so difficult to locate Bowie’s phantom. His apartment block remains mostly unchanged. The main difference can be spotted by comparing photographs. Bowie’s flatmate in the 1970s was Iggy Pop, and he is pictured in front of magnificent carved double doors leading into the courtyard behind the apartment building. These have now been replaced with much more functional wire gates.

But many of Bowie’s other haunts are still there – his favourite cafe in the same block, Neues Ufer (in the 1970s it was called Anderes Ufer), and Bucherhalle, an antiquarian bookshop a few doors away from his apartment. When Cummins went into a cafe next door to number 155, he was shown a well-worn box of red, black and orange plectrums and told they belonged to Bowie, who would sit in the cafe writing songs.

Place is important, not just because it locates someone in time and space, but equally because Cummins believes that place and sound are intrinsically linked. Berlin was crucial for Bowie, himself a fan of the Weimar era, and he admitted that the feel of the city bled into his songs, which he described as “dark and celebratory”. Trying to get clean and shake off the excesses of his life in California, Bowie could walk freely in the streets absorbing the history and culture, and writing in his song Beauty and the Beast, “I wanted to believe me / I wanted to be good / I wanted no distractions / Like every good boy should…”

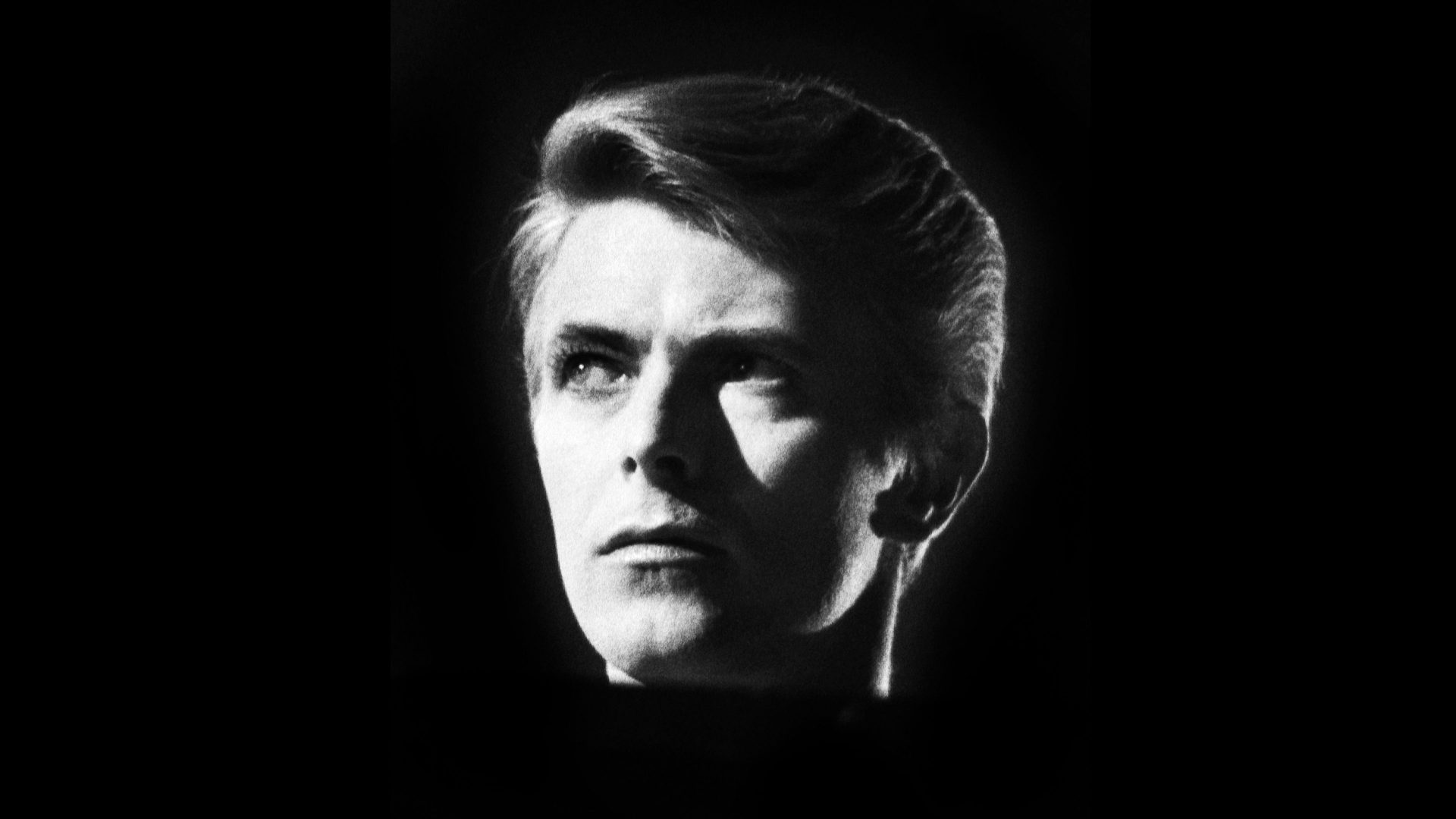

Cummins took photographs while Bowie was living in Berlin but playing concerts in England. In 1976, he played at the Empire Pool, Wembley. Cummins’s photographs could be Otto Dix portraits revealing severe blond hair, high-waisted trousers, and a crisp white shirt. In 1977, Cummins captured Bowie again, this time playing keyboards for Iggy Pop in Manchester. Lurking at the back of the stage, with no light on him, Bowie seemed to crave the same invisibility he desired while walking the streets of Berlin. In 1978, Cummins photographed Bowie twice, once in Newcastle and again in Stafford. One shot from the latter gig shows Bowie from the neck upwards, lit and framed like an August Sander image. If Berlin was seeping into Bowie’s music, it seemed as though the feel of the city was unconsciously contagious, as Cummins’s photography reflected what he called an “austere, 1930s Germanic influence”.

In 2013 Bowie released a song called Where Are We Now?, a moving and nostalgic reflection on his early days in Berlin. He name-checks streets and nightclubs. The accompanying video takes us up the stairs to his apartment, and down the street where he lived. The song breathes wistful remembrance as Bowie sings of “A man lost in time just walking the dead”. Cummins’s book, Mixing Memory and Desire, taking its title from one of Bowie’s favourite TS Eliot poems, The Wasteland, also plays with time long gone. And that is surely one of the many beauties of photography, a fleeting moment captured for ever. The sudden seizure of time stamped into an image, the ghost of an earlier life, leaving us, the viewer, mixing our own memories and desires.

David Bowie: Mixing Memory & Desire by Kevin Cummins is published by Cassell

Gail Crowther is the author of Three-Martini Afternoons at the Ritz: The Rebellion of Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton (Simon & Schuster, 2021)