Reality presses in on all sides with a relentless force, a violence, that drains our energy and dissipates our capacity for belief and for joy. The world deafens with its noise, and our eyes are stinging, saturated, with an ever-enlarging incoherence of information, disinformation and the constant presence of war. Action gives way to distraction. We stare at our screens feeling lost, feeling lonely, finding it difficult to believe in anything, to commit to anything, to live in a way that feels truly alive.

This is a leaden time, a heavy time, a time of dearth. As a result, we feel miserable, anxious, wretched, bored.

We all feel, I would wager, a little like Hamlet.

Since the beginning of 2022 my reality has been utterly Shakespearean. I have been consumed by teaching Hamlet. I do this in a very simple and old-fashioned way. We just read the entire play, line by line, out loud together in class and try to work out what the words might mean – or better, how many things those words might mean.

There is something about the sheer energy of Shakespeare’s language, its percussive intensity, its flurries of sound, its accelerations of association, its concatenated images and tumbling words, that outstrips any attempts to fit those words into some interpretative grid. There is more in Shakespeare’s heaven and earth than can be dreamed of in any philosophy. His language is continually pushing at the bounds of sense, leaving us with a feeling of excited unease, strangeness and even menace.

But what is reality in this most famous of plays? It is unreality, a pervasive doubt that has captured Hamlet’s soul. This feeling of unreality foreshadows our own and illuminates it.

Hamlet is a creature of doubt where all the grounds for trust in the world and in himself have evaporated in fear, paranoia, suspicion and the knowledge of murderous crime. Hamlet’s world is a globe of spies where everyone is being watched in a political regime of total surveillance. This is perhaps why he cannot at any point speak the truth that he has learned from his father’s ghost. Time and place are out of joint. Denmark is a prison. The world is a prison. And Hamlet rattles the bars of his prison cell with words. Indeed, Hamlet’s cell is language. And it is with his endless puns, his sexual innuendoes, his graveside buffoonery and solitary cascades of reasoning, with words, words, words, that he seeks to control the reality that consumes him. He fails.

As it is for Hamlet, doubt is the disease in the body of our reality. Doubt tears at us like rats gnawing away under the floorboards in the house of being. It is like an existential eczema that we scratch at under our clothes.

And this is not intellectual doubt. It is not the cool, sceptical, rational doubt of the philosopher in his study. It is visceral, existential doubt that leaves us feeling derelict and abandoned.

This can be a doubt of others and the benevolence of their intentions, a doubt in the endless news updates that pour in through our smartphones, a doubt in the institutions on which we rely for our safety and wellbeing. And, most of all, the self-doubt that flows from the cruelty of self-regard and that leads us ultimately to the question of whether to be or not to be.

With his doubt, Hamlet kills in himself all love – for Ophelia, for his mother, for the world and for himself. Man delights not him, nor woman neither. And we, most Hamlet-like, spin downwards into a melancholy that sits on us like an all-pervading toxic cloud. We find the world to be a sterile promontory, an unweeded garden full of things dead, rank and rotting.

Shakespeare sets the entire mood of Hamlet with extraordinary economy in the opening scene with the guards on the battlements at Elsinore. Francisco says, “I am sick at heart.” We are not told why he is sad, and Francisco disappears for ever a few lines on, but the mood of melancholy pervades the play.

Doubt kindles our suspicious intelligence and extinguishes our capacity for love.

Is that it? Are we sick at heart? Are we doomed to Hamlet’s supremely intelligent miserabilism, flipping as it does between melancholia and antic mania, between failing to act and acting out? Shakespeare is not in the business of providing answers, and we have no idea what he thought about any major issue of his time (or ours). I count this as a blessing.

Yet there is Ophelia. Where Hamlet implodes with grief that collapses into bottomless melancholy, Ophelia explodes in mourning for her father, Polonius. Her sorrow finds voice in her songs of love and loss in Act IV and in a singularly powerful language of flowers, through which she gives carefully coded blooms to Gertrude, Laertes and Claudius. Obviously, matters don’t end well for her. She is described slivering down the muddy bank into a glassy stream. Yet until her death she is still singing and surrounded by flowers. Ophelia is the true tragic casualty of the play.

It is the direction of her suffering that is significant, I think, and so different from Hamlet’s. It is not inward, but outward. And here is some wisdom, some embrace of beauty in her madness. She does not collapse into doubt but erupts in a movement of pained love. Where Hamlet talks endlessly of suicide and dreams of revenge, he is paralysed at the level of action. Ophelia acts out of love, ends her life, and follows through on her desire. Where Hamlet’s question is “To be or not to be,” Ophelia responds, “Lord we know what we are, but not what we may be.” It is this “may be” that is suggestive, a subjunctive mood that suggests possibility and holds open a small door of promise.

All is always woe, seen in a certain reassuring twilight. Misery never lets you down. Melancholy is a boon companion, reliable in how regularly it shows up in our lives. Nothing is more reassuring than giving in to our own heaviness, the weight of our being that drags us down and from which there seems to be no escape.

As Hamlet’s endlessly chattering soliloquies attest, there is even a perverse consolation in feeling tragically riveted to oneself. It is often what passes in our culture for being smart – a vastly overrated quality, in my opinion.

By contrast, Ophelia holds open the promise of something else. If our reality is suffused with doubt, and doubt kills love, then there is still the possibility of a countermovement to melancholy: the action of love that extends its arms outwards and does not recoil in the face of reality. It is perhaps time to open our arms.

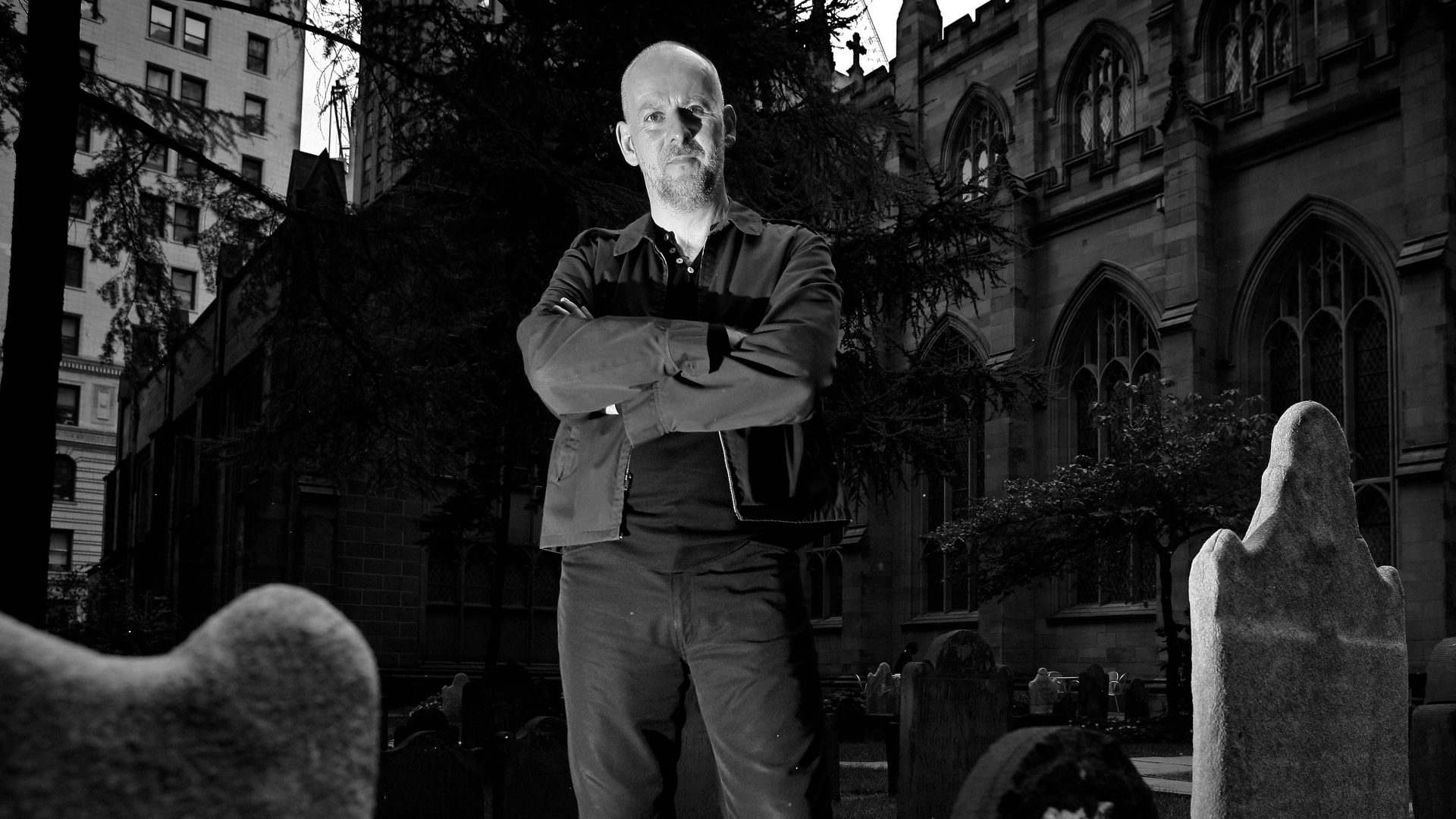

Simon Critchley is an author and a professor of philosophy at the New School for Social Research © The New York Times Company and Simon Critchley