For an operation that can’t get even the simple stuff right, Rishi Sunak’s No 10 can never resist an opportunity to try to be too clever by half – this time with the New Year’s Honours list.

Compared with much of the mire of the UK’s honours system, the New Year’s list is usually relatively uncontroversial. A smattering of national treasures receive high-profile knighthoods or damehoods, various worthies take lesser honours, and a slew of awards aimed at long-serving civil servants and the occasional MP are generally shrugged off as just the way things work.

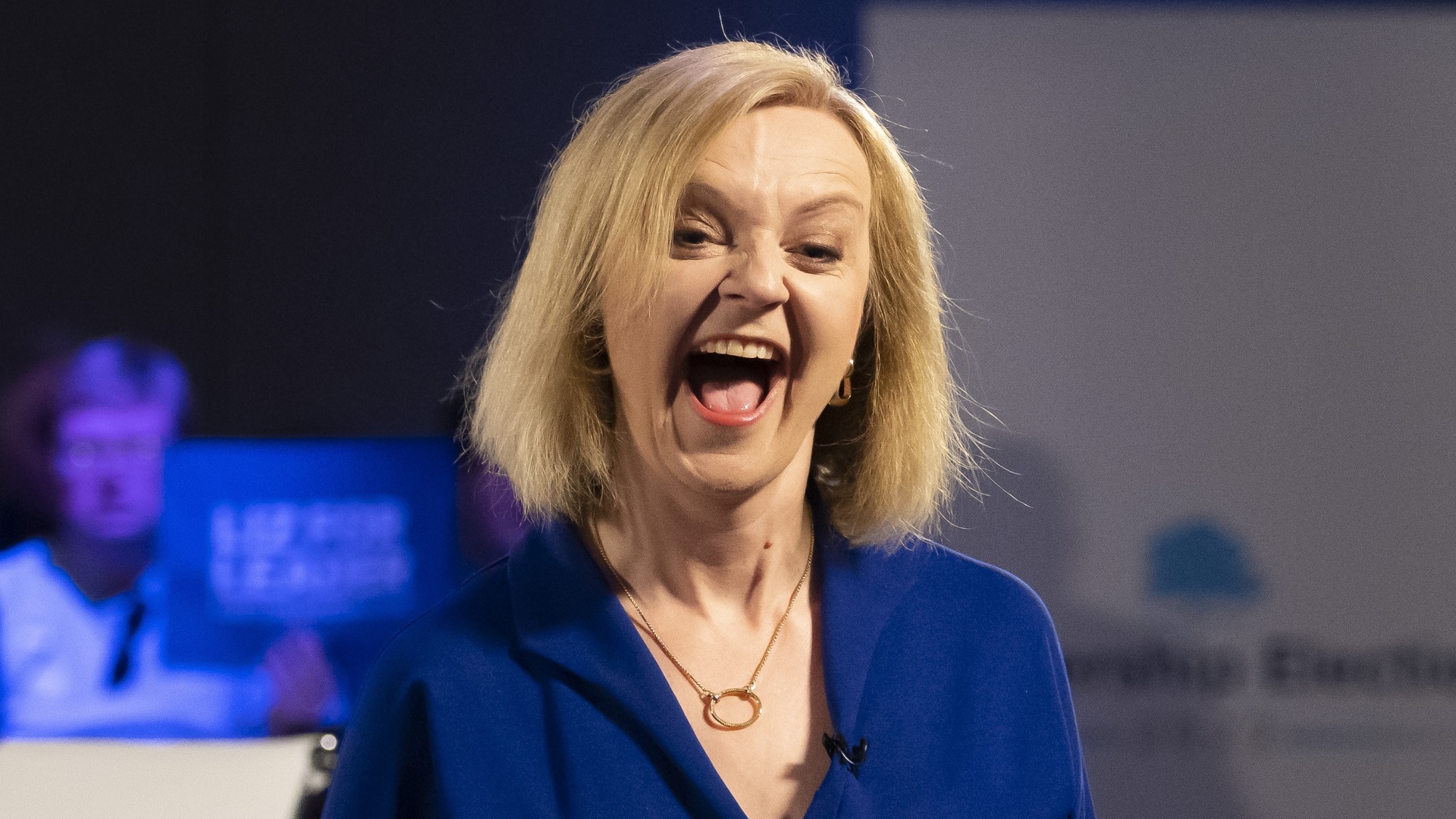

This year was made different thanks to No 10’s decision to sneak out a resignation honours list for Liz Truss alongside the New Year’s honours – a list that included the elevation of three new peers. Truss was prime minister for less than 50 days and yet has created three new legislators for life – including Matthew Elliott, chief executive of the Vote Leave campaign, and Jon Moynihan, a businessman and Tory donor who has given around £700,000 to the Conservatives, Vote Leave and Truss’s own leadership campaign.

These are not appointments that are likely to encourage greater trust in the British political system. Neither are the seven honours given to Conservative donors in Sunak’s New Year’s list, which included knighthoods for John Griffin, the founder of the Addison Lee taxi firm, who has given the party a total of £3m, and the Wetherspoons boss Tim Martin, a keen Brexiteer whose sunny predictions about cheaper food and better trade after leaving the EU have not come to pass.

Just about the only good thing to come from the Truss honours – apart from them inevitably being dubbed the Lettuce List – is that contrary to expectations, the name of Mark Littlewood was not on it. He is the former director general of right wing thinktank the Institute of Economic Affairs, which promoted many of the ideas that sent Truss’s political career down in flames when they were packed into the disastrous mini-budget she cooked up with Kwasi Kwarteng.

Tories have been across the airwaves trying to make out that the Truss list is some form of longstanding protocol, rather than a shameless abuse that lays bare the ridiculousness of how the UK appoints peers to its legislature, and how the honours system works.

Multiple 20th-century prime ministers with longer tenures and greater accomplishments than Liz Truss departed without a resignation honours list, while the example Jacob Rees-Mogg cited defending such elevations was before the 1832 Reform Act – when parliamentary corruption and patronage was all but formally part of the system.

It is obvious that the Conservatives will continue to shamelessly abuse the honours system for so long as it is in their power: should Sunak lose the general election this year, there will be a second resignation honours list of an unelected prime minister in succession. Labour should take the opportunity to make sure it is the last.

The best trick to handling the abuse of the honours system would be to reform the House of Lords so it is no longer appointed, but instead elected – ideally using a proportional system that is out of sync with Commons elections, so the second house is an effective part of the governance of the country, rather than an idiosyncrasy.

Handing out knighthoods, MBEs, OBEs and the like to donors and cronies is cringeworthy – as is having honours with “Empire” in the title in the year 2024 – but it is largely harmless. Few of us take the honours system all that seriously at the best of times; it is attaching a lifetime in the legislature to it that causes the problems.

Labour is said to be considering Lords reform, but many expect the party to back off from actually doing it, especially in their first term of government. If they’re going to stop short of that, there are still ways they can make honours better in future.

If the Lords is going to continue to be appointed, then it should be formalised: each term between elections could allow a fixed number of appointments to the Lords, apportioned by the allocation of seats in the Commons.

Those peers who do get appointed could come off that total regardless of the mechanism by which they’re elevated. If the prime minister wants to appoint a minister via the Lords, that comes off the total. Annual peerages count, and if a PM wants to elevate someone to the upper house when they resign, it comes off the total. That way at least, there are limits.

Some people think a wider reassessment of honours is important, and that there should be some wholesale re-examination of it. The reality is that it just doesn’t matter – almost anything else that parliament could be doing with its time would be a better use of it.

Truss’s resignation honours list was venal, but predictably so. The problems of the honours system are heightened by the low calibre of people currently in high office, but the real problems are that the system allows such people as much leeway as they could possibly want.

Peerages are just one part of the system that needs tightening up against future abuse – there will be much more to do.