There is no getting around it: this winter is looking grimmer with every week that goes by. Such is the scale of the cost-of-living crisis that Citi bank this week predicted UK inflation could hit a staggering 18.6% by January, thanks mostly to the cost of energy.

We feel the cost of energy most acutely when we see our energy bill, for which the price cap is due to go up massively in October, once again in January, and yet again in April – hitting £5,816 a year for a typical family by that point.

For most of us, that’s a quadrupling or worse of energy prices in less than two years, but we feel energy prices in every other cost too: producing goods uses energy, while cafés, shops and restaurants need lighting and heating. When energy is expensive, everything is expensive.

By January, estimates suggest as many as two-thirds of UK families could face fuel poverty – defined as when fuel bills make up more than 10% of income – meaning even relatively well-off households could feel serious pain as a result.

As Zoe Williams noted in last week’s New European, this is the kind of crisis that causes destitution and riots – it closes businesses, leaves households deeply in debt and unable to pay their bills, and leaves people freezing to death. The government seems completely caught off guard by it, with Boris Johnson’s caretaker administration more concerned with enabling the prime minister’s holidays, and insane pronouncements from the candidates to succeed him.

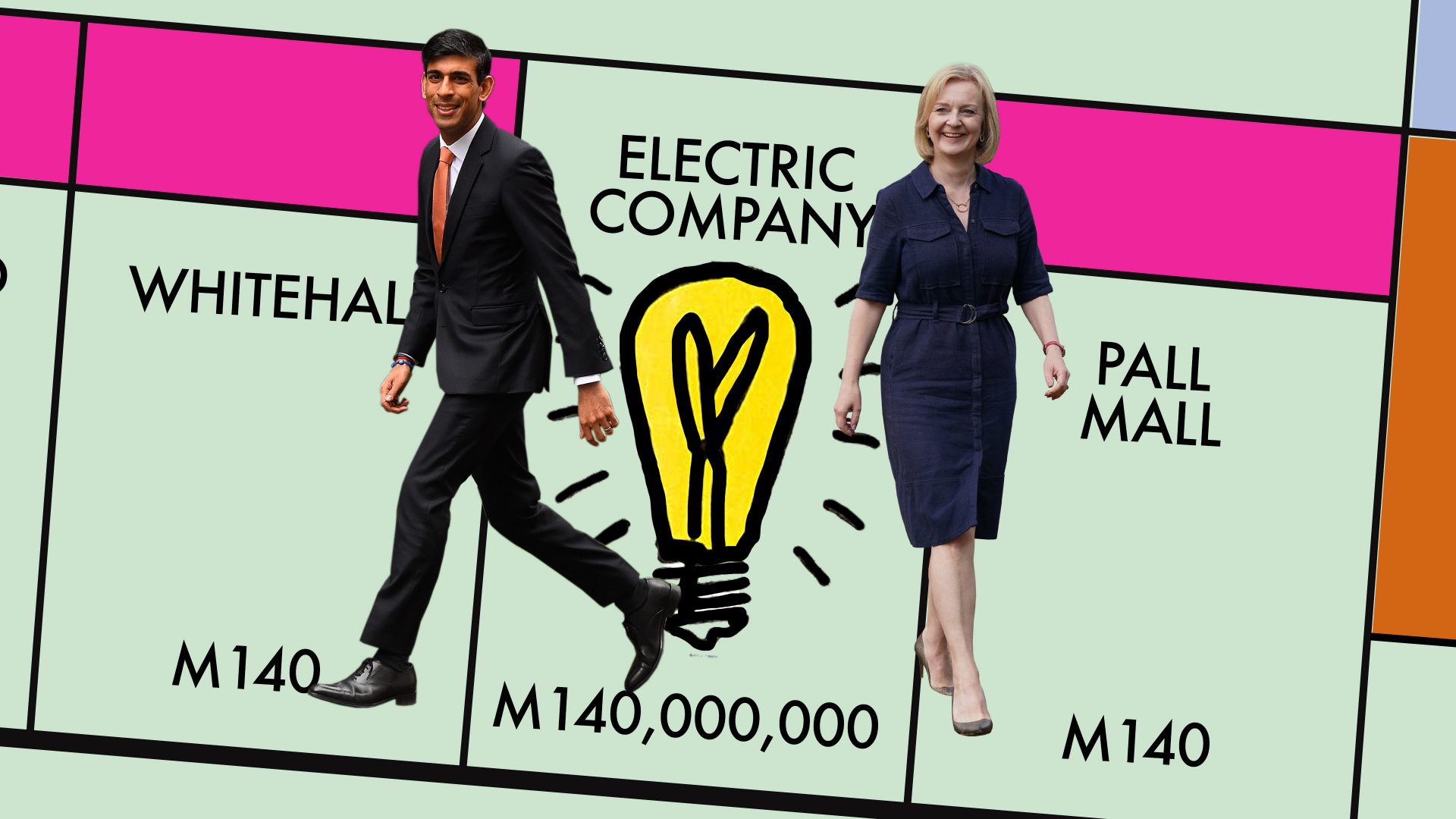

Rishi Sunak has vaguely offered more help after initially vowing to do no more than the £400 to £1,200 he had grudgingly set out earlier in the year, before resigning as chancellor. Liz Truss, meanwhile, has repeatedly said she would offer no more “handouts”, instead offering a small rebate by cancelling the green energy levy (worth about £150 a year), opposing windfall taxes, and cancelling an increase on corporation tax. Her friend, neighbour and probable new chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng has assured Britain that “help is on the way”, without saying what that could entail, beyond a crackdown on profits made by wind and solar energy firms.

Twitter, meanwhile, insists the crisis is easily solved. A dubiously sourced chart suggested energy in the UK was up 215%, versus just 4% in France. Others showed oil company profits against household bills, hinting at an easy solution there. More popular than either were calls to nationalise energy companies.

The reality, inevitably, lies between the two: there is no doubt the government has made years of mistakes on energy and is compounding those now by totally failing to grasp the scale of the crisis. But those imagining there is some sort of easy fix are in fantasyland.

Here’s what’s really going on, and why it’s so hard to fix:

Why is energy so much more expensive this winter?

The short answer is that across Europe everyone is convinced there won’t be enough energy to go around – and when something is in short supply, people will pay much more to secure it. Much of this is, of course, because of disruption and political pressure caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, but there are other pressures for manifold reasons. There is a real fear in multiple European countries (including the UK) that there will not be enough energy to keep the lights on, or factories manufacturing.

This leads to competition between countries to secure the supplies that they are most confident will be delivered. Energy companies buy their energy as “futures”, well ahead of time – they will today be buying gas for delivery on, say, December 1, 2022.

This gas is much more expensive than gas sold for delivery today, because gas in winter is much more useful than gas in summer, which either has to be stored (which is costly, even if you have capacity to store it) or used now. The UK in 2017 closed its largest gas storage site – a move now almost universally recognised as a costly mistake.

Why pay these prices? The cost of extracting oil and gas hasn’t gone up much – and shouldn’t renewables cost the same as before?

It is true that it doesn’t cost much more to extract gas now than it did last year – it’s just that people are willing to pay much more for it. In that situation, which customer will the company sell to? The one offering more cash, or the one insisting that you should accept a lower price because that’s fairer?

The answer for a company looking to make profits is obviously the former – and these are international companies, often owned by major states themselves, that the UK government is in no position to bully into accepting lower prices. Supply is limited, the product is in demand, and so prices rocket even if costs don’t. This is especially true when people are chasing scarce stocks months in advance – if you wait and hope for prices to fall, you may find there’s no energy left to buy.

This is the same choice facing solar and wind manufacturers – they will sell all of the energy they generate whether they sell it for half the price of gas or the same price as gas. Why should people who have invested in renewable generation leave profit on the table if they don’t have to do so? Efforts are under way to offer renewable providers a lower price but fixed for 10 years or more to try to change these incentives, but these won’t pay off overnight.

So: energy generation companies are making record profits – let’s windfall tax them. Problem solved?

There is nothing wrong with a windfall tax against unexpectedly large profits – such as those made by BP this year. Companies invest in the hope of making a good, steady profit. If there is a much larger profit than they would expect, then they should expect at least some of that to be recouped, especially when the profit is coming at such a high societal cost.

That means there’s a very good case for a windfall tax, and it can easily be argued that the current windfall tax is too lenient and can be extended – but it won’t be nearly enough to cover the cost of the crisis. That’s because most of the places that actually extract the oil, gas, or other fuels are not UK companies, and so the profits don’t touch the UK. We can only tax the companies that are within our jurisdiction, and we need to do that (at least somewhat) carefully, lest they relocate their investment or even their headquarters.

What about the companies delivering the energy to our homes? Can’t we tax them more – or even nationalise them?

Given we’re all looking at huge bills with EDF or E.ON’s name on them, it is very tempting to assume they’re the ones making huge profits. Some of them, as a whole global company, are – but these are from their extraction and generation businesses. The UK business that actually delivers energy to our homes are a different matter.

Even in the best of times, the UK’s energy rules cap the profit margin on energy distribution to 2% – and the last few years have not been the best of times, with 29 UK energy companies going bust as wholesale prices rose. The cheap energy from the supposed scrappy start-ups was cheaper because those companies didn’t bother to hedge their purchases against future price rises – meaning that when energy prices rose they had no protection at all.

If the UK acts to absorb the price increase into public finances, that will represent a bailout of these companies – and so we should look at whether that comes in exchange for taking a stake or nationalising the business. It’s just that won’t result in much of an immediate effect on prices – it’s more a matter of fairness.

So… why can France keep price rises at 4% when the UK’s are 215%?

This online figure is (shockingly) a little unfair: the 4% figure for France is for electricity, and is after government action. The 215% in the UK measures the UK’s with absolutely no taking account of the up to £1,200 in support that has been offered. There are also issues around the energy mix – countries with more nuclear and renewables than gas have a smaller set of costs to deal with than those which use more of the latter.

But France was able to cap its increases at 4% for a simple reason – its national energy company is (almost entirely) state-owned and so it can impose this kind of policy with the company’s bosses knowing that one way or another the state will pick up the tab later. For the UK to offer similar, companies need to be reassured the money will come from somewhere.

That doesn’t prevent the UK capping prices – but ministers would probably have to reassure energy companies they would pay the difference, which politically might require nationalisation, too. This is all far more socialist than any incoming Conservative government might like, but the personal and business collapses that would follow otherwise would be catastrophic both practically and politically.

Would keeping the price cap where it is solve the winter crisis?

It would certainly help – but other costs are going up too and it’s likely to be a tough winter anyway. On the energy front in particular, there is the complication that prices are high because we don’t think there will be enough to go around across Europe.

Prices are intended to serve as a rationing mechanism – if something is expensive we use less of it. The mechanism works, but we find it unacceptable when it comes to heating and lighting our homes, and so we need intervention. The scary element if we disconnect pricing from supply is whether or not we can actually keep the lights on this winter – and there are plenty of rumblings that it might not be doable.

It could be a very long, very hard winter. Buying a jumper isn’t going to be enough – the new Truss government will have to be pushed into action. Just don’t expect miracles.