Victor Hugo wrote: “The rich’s paradise is built on the poor’s hell.” One element of that hell, according to both Friedrich Engels and David Harvey, derives from the ruling bourgeoisie’s failure to devise a means of accommodating the despised working (and supposedly criminal) classes, on whose efforts its comfort resides, other than by pushing them from the centre of cities, hiding them away. It was a punishing commute from under the carpet. If, of course, there was a job to go to.

More usually the Zonards worked for themselves, infected hand to gingivitic mouth. The Zone was a terrain vague immediately beyond the limits of the fortifications that encircled Paris. It was unofficial, unsanctioned, an insult to propriety and home to 50,000 people, the population of a town such as Albi or Belfort. It occupied the void between the supposedly salubrious suburbs and Paris’s mid-19th-century fortifications, still indebted to Vauban 150 years after that great engineer’s death, and seldom fit for purpose.

Today’s périphérique follows much of its course. The city’s eastern boundary was still sprinkled with bidonvilles, architecture without architects which architects, conspiring against the lay public, will tell you is not architecture: rackety, rusty, unhygienic, self-bodged and housing an anarchic polyglot population that scraped a living from detritus and scrap. Iron, paper, fabric, pottery, untreated hides, bones, oyster shells. The chiffoniers and biffins (rag and bone operatives) took pride in their trade. It gave them liberty. It was beyond the understanding of the despised bourgeoisie. The main value of the dust heap was not, however, in the troves within the pudding, but in the bricks that could be made from cinders and smelt.

Waste was profitable, the very emblem of coarse capitalism. Dust mountains famously dominate Our Mutual Friend. They reek even more potently in Michel Tournier’s mildly scatological Gemini. The titular twins’ Uncle Alexandre, “The Dandy Of The Sump”, says: “Everything is beautiful, even ugliness, everything is sacred, even shit.” Waste was hymned by the northern French singer Pierre Bachelet: “I had slag heaps for want of mountains.” Mountains that have improbably become lures for tourists and, less surprisingly, for adolescents on trail bikes.

The last of the buildings that occupied the Zone were compulsorily purchased and demolished around 50 years ago. Soon after, on March 21 1973, the “Gaullist baron” Olivier Guichard, who served under Georges Pompidou and Giscard d’Estaing in minor posts, published a “circular” that might more properly be considered a decree. It was an edict of environmental dirigisme, aesthetic control. By the time he was in his 50s, Guichard had just about clawed his way up the ladder to the ministry of economy and land use. He may have been a mere dodgy placeman who was also regarded as a debauched nearly-man. He was denied preferment because Yvonne de Gaulle mistrusted him (his cousin, a member of the OAS – a far-right terror organisation spawned by the French army in Algeria – was murdered by her husband’s mercenaries). Yet Guichard would come to have an immense effect on France’s infrastructure and specifically on its social housing.

The circulaire Guichard made his name or, rather, it is all he is known for. It prohibited the construction of further grands ensembles though it did not actually define what comprised a grand ensemble. There existed, of course, a collective conception. Eight major projects were halted. These tectonic phenomena had precursors that belonged to the 1930s. But they are primarily associated with the Trente Glorieuses, ie 1944 until the oil ran dry. Guichard’s stipulations concerned outsize scale and boorish size, our old friend “affordable housing”, accommodation for elderly and disabled people, measures to counter segregation (though of whom and on what grounds is unspecified), the lack of amenities, transport, schools etc, a cap on the number of new dwellings proportionate to the population of the conurbation where they are being erected, an end to relentless, monolithic homogeneity.

It was to these measured utopias that Zonards, immigrants and refugees would be decanted, along with a local population rehoused from squalid bothies. They were not much more successful than the contemporary Khrushchevka, the mass-produced Soviet blocks. The felicity of Guichard’s timing cannot, retrospectively, have been lost on him. He was apprised that a generation of architects was in broad agreement with him: opposed to functionalism, eager to cast off orthogonal restraints, to exhilarate rather than depress, to eschew the moral, or moralistic, baggage associated with first-phase modernism. They knew what not to design.

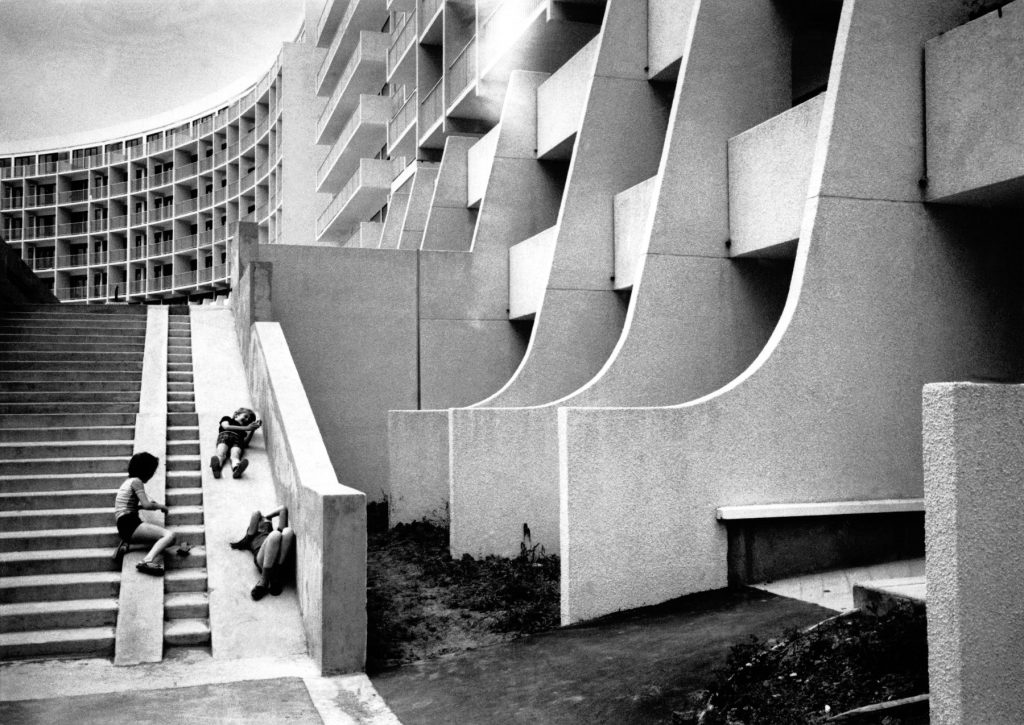

Les Vagues stands on the seafront in Guichard’s own fiefdom of La Baule. It is one of the more spectacular essays in late modernism (which has nothing to do with the kiddy-friendly play-pen-and-sandpit of postmodernism). La Grande Motte by Jean Balladur, cousin of the sometime presidential candidate Édouard, Edmond Lay’s Meriadeck quarter in Bordeaux, Claude Le Goas’s Montreuil conservatoire, the Tour Totem by Michel Andrault and Pierre Parat on the left bank of the Seine in the 15th arrondissement, les Orgues de Flandre by Martin van Treeck in the rather rougher 19th – these do not follow the same template, indeed they might be from different eras. There was no norm, no consensus, only a farouche diversity (of colour and sculptural forms) akin to that of the later Brezhnev imperium. The best known and most admired of these exercises in the redefinition of modernism can be glimpsed from trains going to and from the Gare de Lyon.

Gérard Grandval’s Les Choux de Créteil were only a year away from completion when Guichard’s blow struck. It was too late for any fate other than to go to term. Besides, it was an inadvertent exemplar of what was to come: inventive, largely unprecedented, frightening or funny according to mood and light, and bizarrely cuddly. Whoever coined the nickname – the Cabbages – had a visually impaired conception of brassica. The dozen or so towers do certainly possess a leguminous mien, but the veg in question has yet to be bred and the towers are, equally, zoomorphic. They might have been sired by a marmot. The name is supposed to allude also to the market gardens that once graced this part of the Parisian conurbation and to the Choucrouterie Benoist, an immense factory that salted and fermented cabbages – France is, gastronomically, a northern European country, hence its ravenous appetite for choucroute.

Although Créteil was, according to Pierre Billotte, its first mayor, a new town and the “model for cities of the future”, it was not un ville nouveau. From this distance the taxonomy of urban forms seems a bureaucratic irrelevance. It is difficult to distinguish Créteil from such neighbouring burghs as Ivry or Vitry, which were fully accredited villes nouveaux yet are mere names today in the thick stew of Paris’s satellites. Where one ends and the next begins is a matter of varying degrees of autonomy, administrative discrimination and stabbings per 1,000 head of population rather than architectural identity.

Despite les Choux, despite Renée Gailhoustet and Jean Renaudie’s ingenious Escheresque town centre at Ivry, despite Manuel Núñez’s “camembert” at Noisy, despite even Ricardo Bofill’s XXXL classicism at Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines and countless other sites, all Guichard’s controlled future had to offer, eventually, was a novel sort of slum and better shelter on stairways for free-range pharmacists and their €500-a-day 12-year-old look-outs.

This, evidently, was not what Guichard intended. He subscribed, informally, to the deterministic fashion of the day. He may never have heard of, let alone read, BF Skinner. But he did make a link between environment, domestic conditions, social amenities and their pressure on behaviour. The right sort of urbanisation would, it goes without saying, foment good behaviour. The right sort of urbanisation, should it be devised, would cause the rats in this experiment (let’s call them people) to achieve at least a modicum of civility and decency. But it didn’t.

Hence the relentless “settling of scores” by gangs, murders of teachers, threats to synagogues. Hence the now traditional car-burning season in late autumn. Wackily shaped windows, allusions to ancient Greece, homages to space exploration, ostentatiously anti-functional exterior decor, imitations of geological formations… these and countless tics and gimmicks do not salve the race. There is of course always hope. A few kilometres from les Choux, Jean Nouvel’s recently completed Tours Duo will no doubt have some effect on those who work in them. And on those who come after them. They will recall the hope that the now-worn buildings once excited. But what exceptional buildings of any generation achieve is not machine smoothness but aesthetic bliss, untrammelled delight at the manipulation of space and materials.

They are monuments to humankind’s need to make art, art that pretends to fulfil a social function, that meets need. The interiors of les Choux are disquieting. The apartments are clumsily shaped. Its longevity – many of its contemporaries have been consigned to rubble – is irrespective of its banal utility. It is architecture for architecture’s sake. It salutes its maker.

Grandval’s subsequent work gives the clue to his aspiration at Créteil. It includes alpine lodges constructed like boats, solar-powered houses, “organic” bubbles, plastic chalets. Buildings with polyvalent versatility acknowledge that purposes will change and that the vessel into which yet unimaginable future uses will be poured is an end in itself.

Jonathan Meades is a writer and filmmaker who specialises in architecture