In 1930, as the global economy nosedived into the Great Depression, the economist John Maynard Keynes published a startlingly upbeat essay called Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren, laying out his vision of a future where people would use technology to shake off the shackles of subsistence and work only 15 hours a week.

Seventy-five years later, a Portuguese economics student read this essay on a gap year and became hooked on the idea that the old ways of doing things could, and should, be changed for the good of the economy, people and the planet.

Now that student, Dr Pedro Gomes, has turned his passionate obsession into a book – Friday is the New Saturday: How a Four-Day Working Week Will Save the Economy. Published last August, the book argues that a four-day week would stimulate demand, productivity, innovation and wages, while reducing unemployment and helping to stall the rise of populist movements.

Gomes’s timing was serendipitous. He decided to write the book in 2019, partly because the UK Labour party’s election manifesto included a pledge to cut the working week to 32 hours. Gomes welcomed the inclusion of the idea, but felt the arguments around it were rather weak. He wanted to provide better ones. Then the pandemic – which would redefine our understanding of what was possible in terms of modern human adaptation – gave him the time to finish his treatise.

Gomes, an economist at Birkbeck, University of London, says the pandemic also showed that government leadership is necessary to turn that four-day-week dream into a reality. And that’s because the idea has already been around for a long time – Richard Nixon was one of the earliest proponents when he was US vicepresident in 1956 – just as the practice of working from home predated the pandemic.

“We can’t expect people or firms to adapt spontaneously. Working from home as a practice already existed and economists had already shown that it increased productivity … But it was never adopted. It had to be an external force, in this case the pandemic, that forced that. It’s very similar to the four-day week in that sense. Firms are experimenting with it and signing up for trials. But the shift to make it mainstream will require something from above,” he tells me.

Today Gomes’s book, and the Keynesian ideas that inspired him, are catching a zeitgeist wave as people re-evaluate what work means after two years of upheaval that saw many retreat into home-based digital offices, while others suffered burnout and extreme stress on the healthcare and retail frontlines of a terrified society.

As part of this global rethink, or what some are calling “the Great Resignation” because of the numbers deciding not to return to their old jobs and previous ways of working, many companies are carrying out trials of four-day weeks, cutting hours to 32 while maintaining pay. This reform is also known as the 100-80-100 model: 100% of the output for 80% of the hours and 100% of the wages.

That formula was the brainchild of Andrew Barnes, an entrepreneur from New Zealand who co-founded the global 4 Day Week Campaign after reading an Economist article that said most workers were only productive for between 1.5 and 2.5 hours of a typical eight-hour day. He started with a trial of a four-day week in his own business in 2018 and now his organisation coordinates trials across the world.

In the UK, at least 30 companies, ranging from a fish-and-chip shop to a telecoms firm to digital animators, have signed up to a six-month trial, which is due to start in June and will run alongside trials in the US, Ireland, Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

Joe Ryle, the director for 4 Day Week UK, says they expect to see similar results to those achieved during a 2015-2019 trial in Iceland. Then, around 2,500 workers across the economy cut their hours from 40 a week to 35 or 36, but retained the same pay. Productivity rose or remained the same and workers said they felt less stressed while their work-life balance improved. Many decided to continue with the reduced hours.

“Other benefits we are looking at include benefits to the environment, bringing down carbon emissions, and also the benefits to gender equality, where chores are shared more equally between men and women,” Ryle said.

After the UK trial, which is being overseen by academics at the universities of Cambridge and Oxford, plus Boston College in the US and the think tank Autonomy, a report will be presented to MPs and parliament. Scotland is also carrying out a six-month trial with a £10m fund from the government, while in Spain a two-year trial with initial financing of 10m euros (£8.4m) is due to start later this year and involve up to 300 companies. It is being organised by the government and the left wing Más País party.

Íñigo Errejón, the founder of Más País, is a long-time believer in a four-day week and regularly speaks of how Spain should lead the fight for this reform. Announcing the trial project last year, he tweeted: “We have opened a real debate of the time. That always arouses controversy, because it opens a gap. What more important thing does politics have to deal with than life time?”

Others are taking a slightly different route to a shorter working week. In Belgium, the government agreed in February to allow Belgians to compress their hours into a four-day week without a loss of salary. In other words, they would work longer days to get that three-day weekend. The prime minister, Alexander De Croo, said the aim was to create a more dynamic and productive economy in the wake of the pandemic.

In the US, congressman Mark Takano from California has introduced federal legislation to lower the overtime threshold to 32 hours a week from 40 hours. Writing in The Guardian, he said workers were ready for a new normal after the pandemic and that pilot programmes showed gains of 25-40% in productivity as well as improved work-life balance, fewer sick days and better morale.

Ryle says the pandemic was the “catalyst for the momentum”, with most of the companies involved in the UK trial saying they felt they had to embrace a shorter week to retain staff and make sure they were not left behind by competitors offering more attractive packages. He feels a change is inevitable.

“If you think about greater automation and more technology still to come, you’re going to have to reduce the working week anyway to share the diminishing amount of work more equally across the economy. A fourday week is a natural way to do that.”

To those who say the change would cost businesses too much, Gomes retorts that increased productivity will offset this, and even cover the cost of hiring extra workers if needed. Rested employees work more intensively and make fewer costly mistakes, he says. They are also less likely to call in sick and more likely to stay with the company, meaning new people do not need to be trained to take their place.

Some kind of workplace revolution does seem overdue; everything has changed since Henry Ford introduced a five-day, 40-hour week at his US car plants in 1926, but we are still stuck with that 5-2 division. For instance, today more women work outside the home, which means that evenings are no longer as restful as they were in the 1950s and 60s when men came home to a clean, calm home. Now, evenings and weekends are often all about chores, with both parties in a couple having to play catch-up after working more intensely than previous generations, not least because of the always-on demands of technology. As Gomes says, it’s not that we want more rest. It’s that we have less real rest now than we did before.

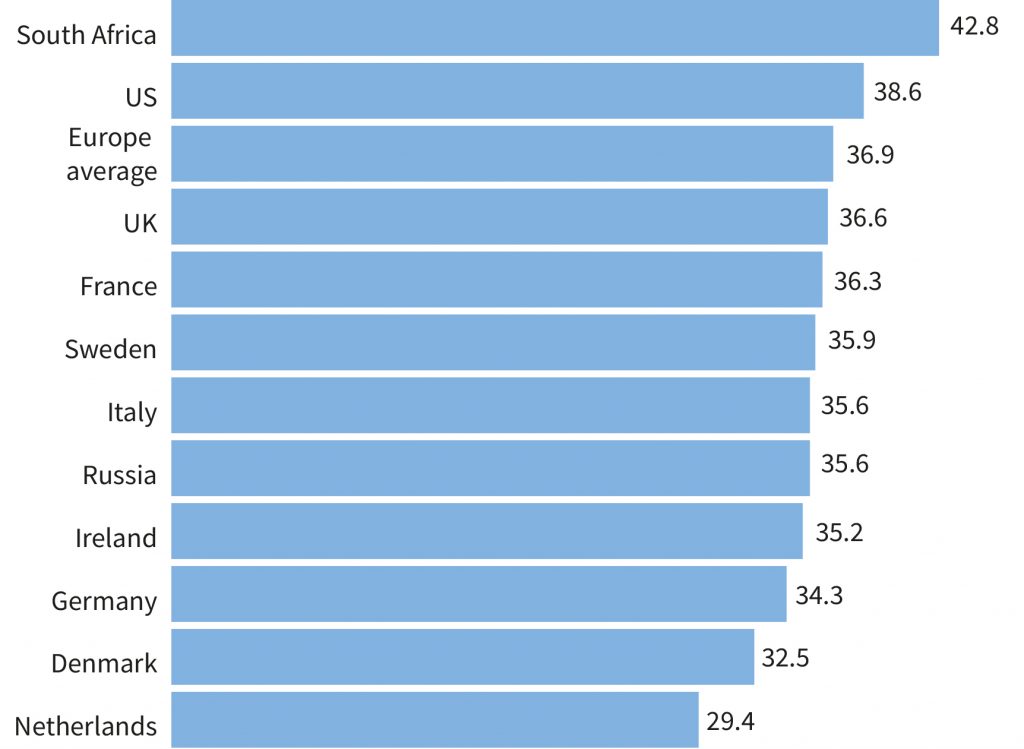

It’s perhaps no surprise, then, that women are particularly receptive to a four-day week. In the UK, 25% of the workforce is part-time, and of that group 40% are women. In the Netherlands, the proportions are 50% and 80% respectively. Gomes says these figures speak to a desire for more time to do other things, but when you work part-time you are also paid less and frequently passed over for promotion in workplaces still often dominated by the cult of presenteeism. A four-day week offers a fairer solution, he argues.

Ryle admits some sectors will find change more challenging, but that shouldn’t be a reason to do nothing. “Take NHS workers or teachers. They are the most burnt out, overworked, stressed-out workers in the country and actually we should be prioritising those sectors.”

A shorter working week may be on the cards for some, but it will not be the only legacy of the pandemic. Julia Hobsbawm, chair of the Workshift Commission at the Demos think tank and author of The Nowhere Office, says the new post-Covid leitmotif is mobility. “I think the phase we’re in now, the nowhere office, that liminal space where everything is up for grabs, the questions of mobility, freedom, flexibility and fairness are now dominant themes,” she said at a recent event on the future of work at the RSA.

Hobsbawm, who is the daughter of the historian Eric Hobsbawm, acknowledges that this flexibility will not be available for everyone, and she divides the world into hybrid haves and have-nots – those who cannot work from home and who perhaps should be paid a premium for this.

Gomes believes the four-day week still offers the best chance of improving workers’ lives across the board. It is a radical idea, but unlike other radical ideas – he cites Brexit as an example – it is creative rather than destructive, and unifying.

“People might be scared that it will hurt the economy but, as an idea, it’s something that everyone likes,” he says, adding that as such it would also act as a foil to populists.

“The rise in populist movements is because the economy is not working for everyone and it hasn’t been over the last 40 years… Brexit was also a consequence of (this)… The four-day week will also be disruptive but it is for an outcome that everyone can agree on. Yes, it will be hard; it means firms have to work better, workers have to work better, governments have to work better, teachers have to be better, everyone has to be better but look at what we are trying to get – it’s really worth it.”