The great British beer revival, led by the success of the new craft beer micro-breweries, didn’t last long. In the last 18 months, over 100 small brewers have rung the bell for last orders and, not surprisingly, Brexit is being blamed.

Hospitality – pubs, bars, hotels, restaurants, cafes, coffee shops and sporting and corporate events – is one of the things the UK does well. The industry is huge, the third-largest employer in the country after retail and the health service. It’s worth £93bn to the UK economy, exports £20bn a year, employs 3.5 million people and pays £54bn a year in tax.

You might think that the government would want to support such a success story by helping it recruit staff and attract tourists. But instead, hospitality is being strangled by red tape, is desperately short of staff and is begging for help.

We saw this coming. One of the first events I spoke at after the Brexit referendum was a conference for the hospitality industry in London. I asked how many had voted for Brexit and only one person put their hand up; the owner of a catering company. She said she had voted to leave the EU because she thought more jobs in the industry should go to British workers.

But when I asked her how much she was willing to spend on training British workers to do the work now that she had voted to end the free movement of workers across the EU, the answer was “Nothing, that is the government’s job”. I imagine she is still waiting for that help and training to arrive.

Until recently the Conservative Party was regarded as the party of British business. Its instinct was always to give business exactly what it needed to prosper. Now it tells companies when and who they can hire, how much they can pay them, ties them up in red tape applying for visas and then lectures them on not taking the opportunities they are being offered. Meanwhile, real people lose jobs, money, their businesses, and their livelihood.

Even Le Gavroche, the jewel in the crown of fine French dining in London, has been affected. It is closing in January; partly because Michel Roux Jr wants a better work-life balance, but he also mentioned that giant pain in the derrière: “Brexit has put a huge spanner in the works in terms of supplies, staffing and costs.”

It is a common complaint. Andy Lennox runs Fired Up Hospitality, a Dorset-based chain of restaurants and bars with 170 full-time staff. He says: “I have definitely seen it happening, how many staff have left the country is staggering.” Lennox does not think this is all bad news, as it has made the industry train and pay its staff more. “It’s driven wages up, which is a good thing, but it is really hard to expand and a lot of people are now opening for fewer hours,” he says.

The industry is losing many experienced professionals, and getting replacements is expensive, especially if they come from abroad. “It is £3,500 just to get someone into the country, even before you have paid them any wages,” Lennox told me. “Red tape, visas, health insurance, it is difficult.”

A survey last year by the Office for National Statistics set out the damage that has been done to the hospitality sector by leaving the EU. It found that the largest fall in total employment was seen in accommodation and food services. In just two years the number of jobs held by EU nationals has fallen by 25%. Covid sent many of them home, and when the government told them that they were no longer welcome, almost 100,000 never returned to the UK hospitality sector.

As a result, the number of vacancies in the sector has soared by 48%. The government tells the sector to employ British staff instead of “employing cheap foreign workers”, but with an incredibly tight labour market that is never going to happen. There are just not enough workers in the UK to do the work.

Recruiting from abroad is now far more difficult, as those looking for work in the UK now require a work visa. In addition to the minimum qualifications requirement and an English test, there is also a salary threshold of £25,600 a year and the need for a full-time job offer, plus you have to pay an NHS surcharge of £642 a year. All are massive hurdles for the industry, which requires a certain number of low-skilled, part-time or seasonal employees to cope with tight margins.

That is why the hospitality industry is pleading with the government to let it join its list of industries and trades that are exempt from those visa rules – so far, to no avail.

The government is hoist by its own petard here. It is desperate to reduce the immigration numbers and so it is very reluctant to offer visa exemptions to sectors with a lot of low-skilled jobs. It is actively damaging the British economy in the process, in an attempt to hit an arbitrary immigration target.

As a result, hospitality is having to pay more to attract fewer people. That is on top of the current broader economic pressures. Energy costs have risen dramatically, interest rates are higher and food inflation has peaked at 19.2%, the highest in 45 years. Eating or drinking out was already beyond the budget of many people; now more and more are joining those shut out by prices.

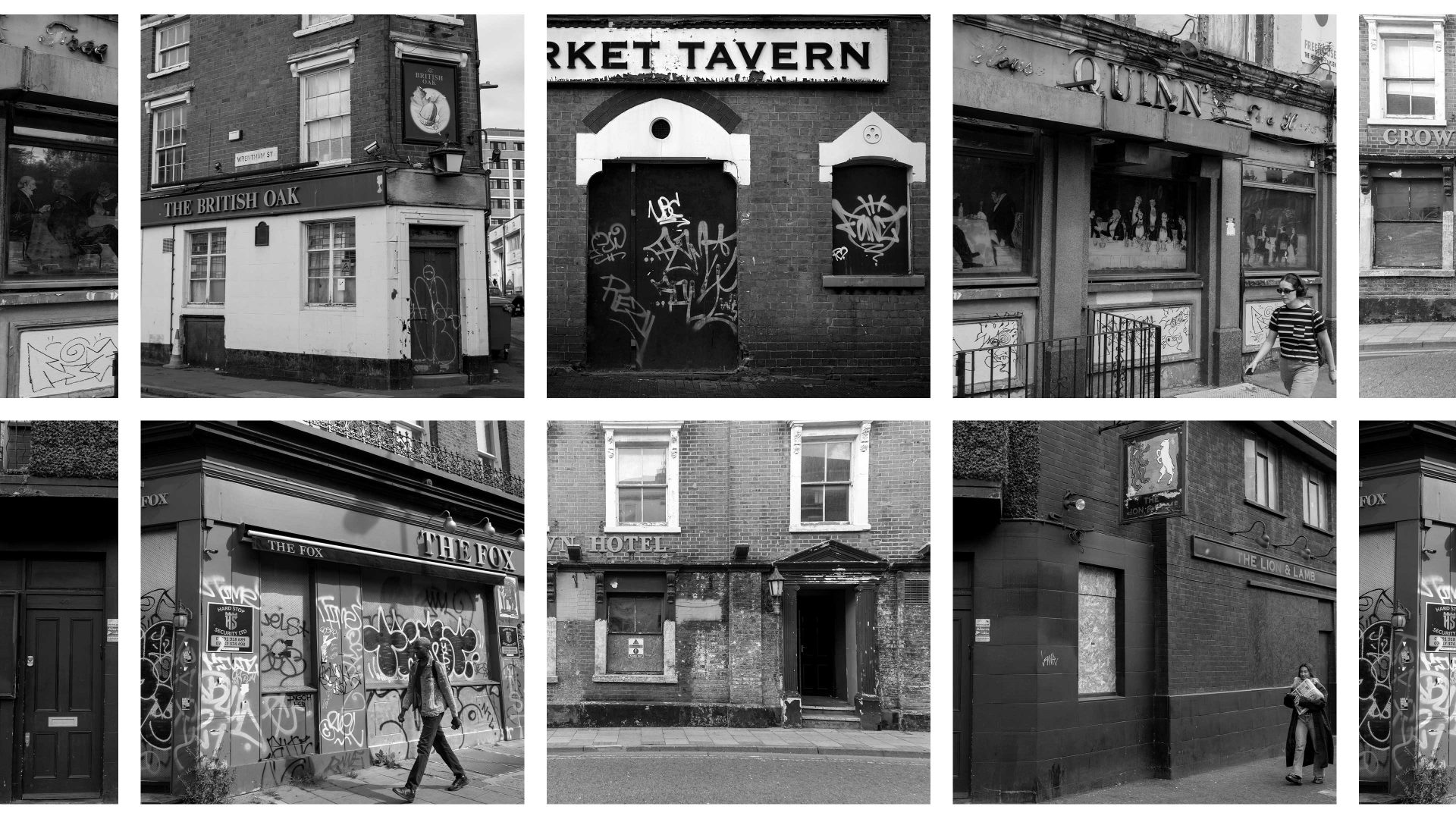

Pubs, hotels and restaurants across the country have responded by turning away events, closing earlier or not opening at all on certain days. Many have taken more expensive dishes off the menu. Margins are being squeezed and profits are down.

At this summer’s annual conference UKHospitality, the industry lobby group, presented a report showing that with the right policies in place the industry could boom and “hospitality could increase its direct contribution to the economy by £29bn and create half a million new jobs by 2027”.

It also presented a “worst-case scenario”, with the industry contracting by 1% over the same period and employing 600,000 fewer staff. Which scenario do you think current policies make more likely?

So if you are thinking of popping out for a pie and a pint, it might be best to do it sooner rather than later…