On Wednesday morning, the UK’s inflation rate was reported to have fallen to the lowest level since the cost of living crisis began. Predictably, Jeremy Hunt and Rishi Sunak have claimed this as evidence they have everything under control, the economy has turned a corner and brighter days are ahead. They are now pinning their electoral chances on it in the general election on July 4.

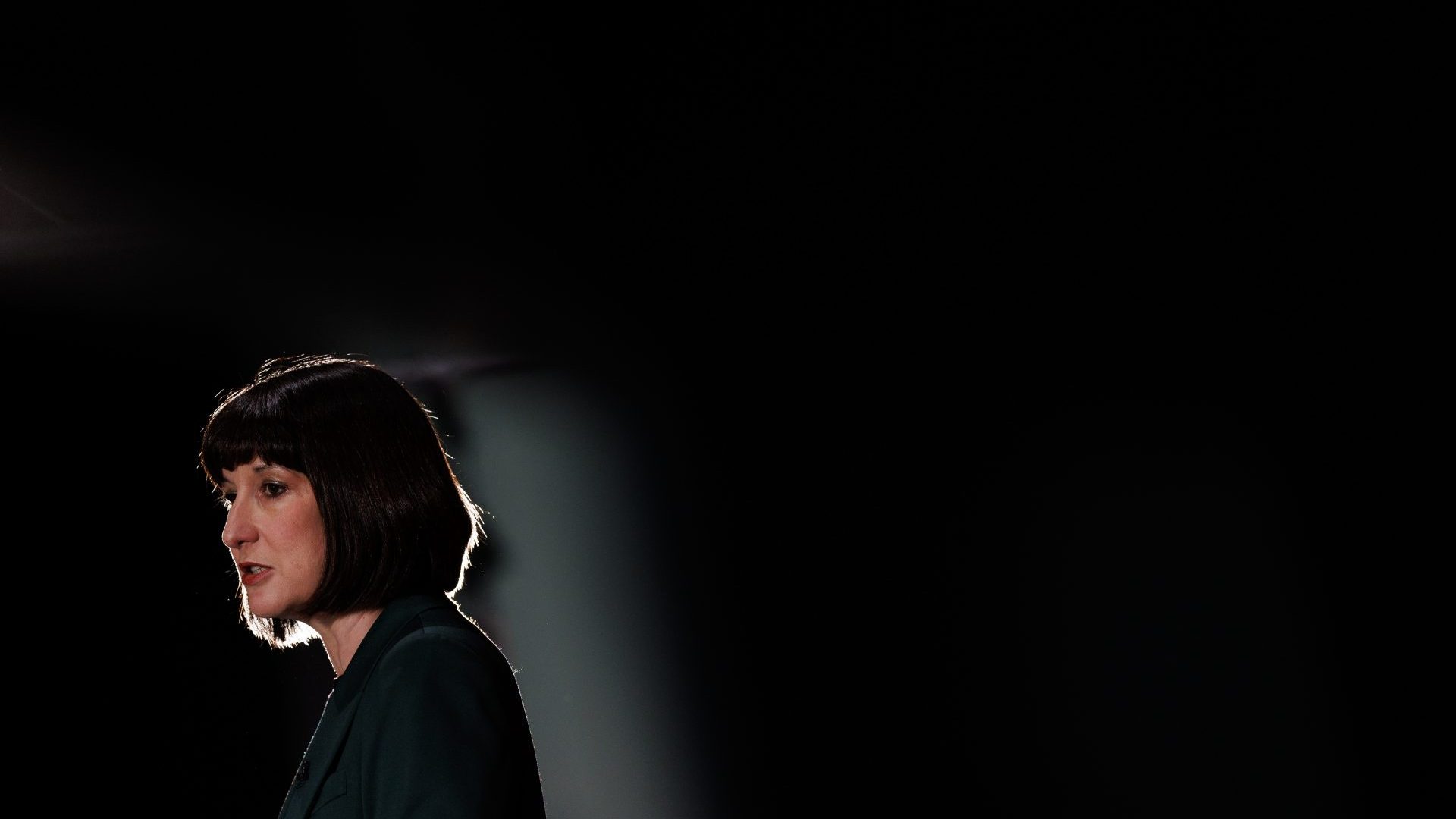

Challenging Hunt for the keys to the number 11 Downing Street, and for the chance to be the UK’s very first female chancellor, is Labour’s Rachel Reeves. Two weeks ago, in response to figures showing the UK is out of a technical recession, Reeves accused the government of “gaslighting” the British public over the state of the economy and the Conservatives’ message that their plan is working.

Reeves may be right about the government trying to mislead the public, but people simply don’t believe them. While the headline measure of inflation is improving, a recent poll by the campaign group Stop the Squeeze found that close to 90% of the public think the cost of living crisis is still ongoing. It is still a bleak picture for many people in this country. UK prices have risen by 22% over the past three years, rent inflation is at 8.9%, and the need for food banks has reached a record high.

What neither the government nor the opposition are willing to be honest about is that conventional monetary policy may have got it wrong on the cost of living crisis. If the shock to the economy is supply-driven (as is the case with our current crisis with global disruptions to supply chains because of the impact of the Russian invasion of Ukraine), then tackling the causes and consequences of the shock should mainly be the responsibility of government fiscal policy (and co-ordinating fiscal policies with monetary policy).

It was convenient for the government to absolve itself of the ability to actually tackle the causes of inflation, which could have meant much more ambitious fiscal policy than one-off payments to protect low-income households from the worst impacts of it. Disappointingly, the opposition too seems wedded to the Bank of England’s current mandate to keep inflation at around 2% using interest rates as its primary macroeconomic tool.

We have good reason to believe that hiking up interest rates has exacerbated the crisis for lower income groups, and in particular, women who had not only borne the brunt of a decade of austerity policies in the UK but had also lost out considerably during the pandemic.

Women in the UK provide 50% more unpaid care and domestic work than men. This leaves women with less time for paid work, which means they earn less per hour than men, have lower weekly incomes, are less able to save than men. This is why women are the ‘shock absorbers’ of poverty, with some groups of women including those on low incomes, lone parents, Black and ethnic minority and Disabled women even less able to afford rises in food, energy and housing costs.

A new report by the Women’s Budget Group highlights some of the alternative fiscal measures taken by five of our OECD peers, and the likely gendered impact of those measures. One of the most obviously gendered policy responses is childcare, where women make up the majority of the workforce as well as the majority of non-working or part-time working parents.

The Australian 2022 budget ushered in a $4.6 billion investment in increasing childcare subsidies alongside an increase in provision and flexibility of parental leave. The Canadian and Dutch governments also increased childcare support.

It is refreshing to see governments treat childcare as such crucial social infrastructure, but the implementation of expansions and reforms must be done properly. The UK government promised an expansion of state-funded childcare which is underway but is beset by capacity and funding challenges.

Housing inflation has been compounded by the rise in interest rates. While several countries including the UK took measures to support people through higher housing benefit in the short term, countries including the Netherlands, France and Spain intervened directly in the rental market with rent controls and freezing of evictions providing greater medium-term housing protections for their populations.

Spain saw a relatively rapid decline in inflation from its peak in July 2022, following fiscal policies aimed at inoculating households from price shocks. The centre-left Spanish government capped rents at 2%, reduced VAT on energy bills and food, reduced public transport costs and discounted fuel prices.

They also took comprehensive measures to lift incomes which, according to conventional economy theory, would be considered ‘expansionary’. The minimum wage rose by 47% between 2018 and 2023; benefits were increased by 15%, and state pensions were increased by 2.5% in 2022, 8.5% in 2023, and 3.8% in 2024.

Conventional economics would expect Spain’s fiscal interventions to result in a wage price spiral, with wages chasing prices and prices going up in response. But this has not materialised. And those on low incomes including women in Spain will have felt the benefits.

When Spain increased the minimum wage in 2023, labour minister Yolanda Diaz said the minimum wage was, “the best, most feminist tool to improve women’s social rights”.

Whoever is in government next – and in opposition – should learn from Spain and other countries’ recognition of the importance of income protection, including benefits and state pension, and consider permanently indexing them to inflation as the Netherlands, Canada and France have also done. They should also take note of the challenge to economic orthodoxy posed by Spain’s approach and ensure better coordination of monetary and fiscal policy, especially when inflation rises as a result of supply-side issues.

The global economic environment does not look like it will provide periods of economic stability any time soon, and it cannot be women who pay the price each time there is an economic shock.

Erin Mansell is head of communications and public affairs at the Women’s Budget Group, the UK’s leading feminist economics think tank, providing evidence and analysis on women’s economic position and proposing policy alternatives for a gender-equal economy.