Some people never learn. By unhappy coincidence, many of these people are currently running the Labour Party.

After James Cleverly crashed out of the Tory leadership race, leaving only Kemi Badenoch and Robert Jenrick, one Labour MP texted the Guardian to jokingly ask if they needed to declare the result as a gift. Another told the New Statesman it was “just the news we needed to cheer us all up”.

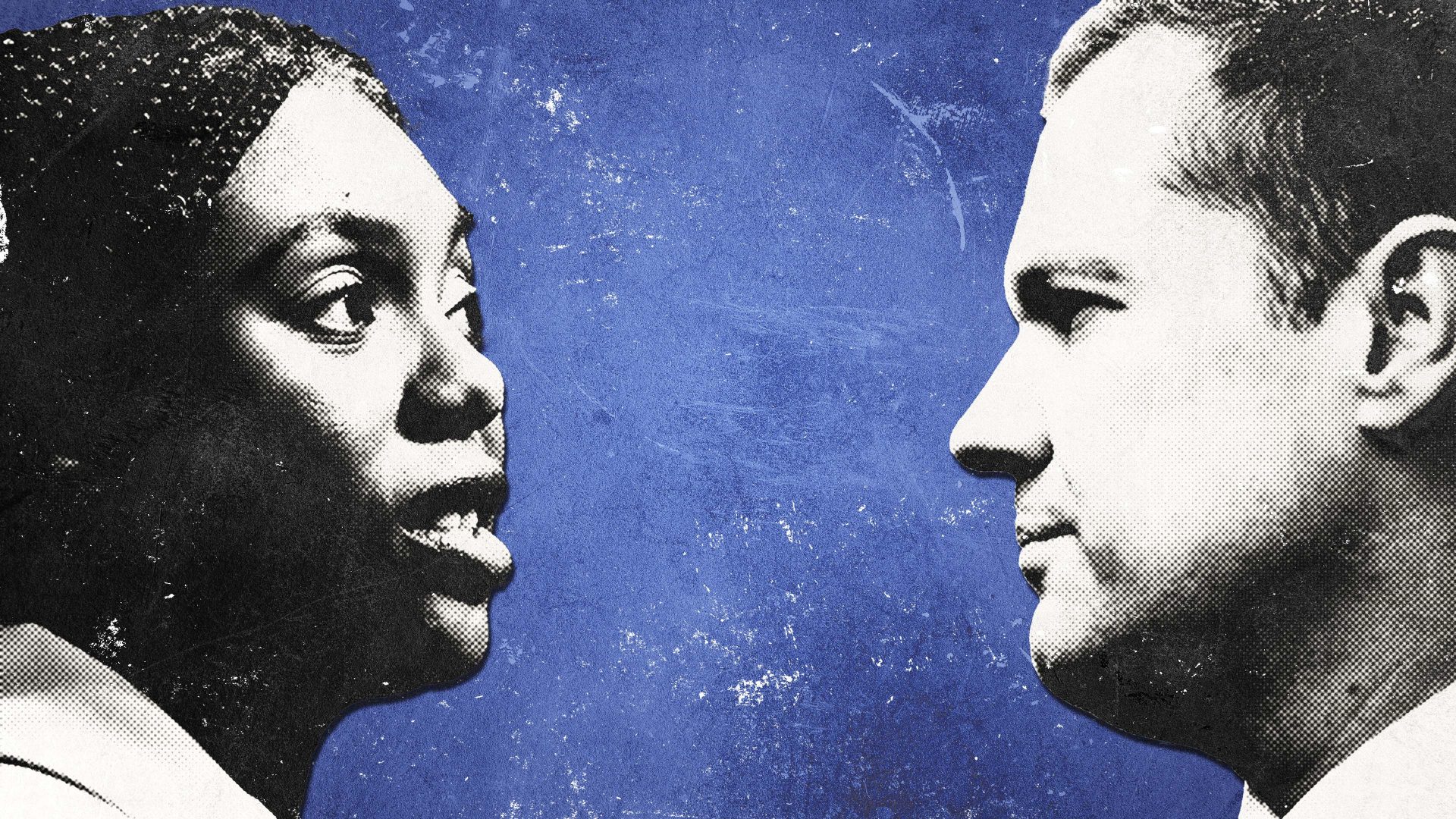

It is true that Cleverly showed signs of being a more relatable media performer. With net favourability ratings of minus 26 and minus 24 respectively, Badenoch and Jenrick are both hugely unpopular – about as unpopular as Keir Starmer.

They are tribunes of a party in which “cultural Marxism” – a far right, anti-Semitic term – has become common parlance. Both condemned this summer’s riots, but used them to argue for even harsher border controls.

It seems obvious to many commentators that Starmer’s sensible Labour Party must logically defeat a hard right Tory party. Perhaps the events of the past decade – in which the centre collapsed and the nationalist right surged – passed them by.

Exceptions are rare. Macron beat Le Pen twice, but has installed a prime minister dependent on her tacit support. It was the left wing New Popular Front that saw off the far right in this year’s legislative elections. Biden beat Trump, but only after the disaster of 2016 – and Trumpism is alive and kicking.

The centre is failing because it ran out of ideas 16 years ago and has spent the intervening period making people’s lives shorter and more miserable.

In 2008, Britain led the world in financial deregulation. The consensus established by Thatcher and continued under New Labour had de-industrialised the country, sold off social housing stock, and privatised large parts of the public realm.

Then, rather than reassess this consensus after the crash, our political establishment doubled down. Neo-liberalism became austerity.

For many communities, the most damaging Tory administration was the coalition led by Cameron and Clegg. Benefits and local government were hammered, and precarious work boomed. In 2010, the Trussell Trust handed out 61,000 food parcels; in 2015, more than a million.

In the decade to 2018, the proportion of the adult population being prescribed antidepressants doubled to one in six, concentrated in places like Blackpool, Sunderland, Skegness. In the same areas, life expectancy went down after a century of rising continuously.

This was the backdrop to the EU referendum. Running Another Europe is Possible – the left’s shoestring anti-Brexit campaign – it was exasperating to observe the complacency of fellow Remain campaigns.

George Osborne warned of falling house prices. The official campaign, Stronger In for Britain, seemed incapable of challenging the Leave campaign’s core narrative on immigration. It warned of abstract damage to “the economy” while featuring almost every prominent pro-austerity politician. They may as well have put Darth Vader on the leaflets.

We are living in a constant repeat of this moment. The Brexit project was not designed to end. As Robert Jenrick’s position on the ECHR makes clear, the nationalist right will never run out of international frameworks to withdraw from, just as they will never run out of migrants to scapegoat.

When the last government introduced a de facto ban on asylum seeking, Jenrick resigned because it wasn’t tough enough. Badenoch is the standard-bearer for the war on woke. As leader, either would reaffirm the Conservatives’ role as the British wing of the nationalist franchise now tearing through Europe’s politics.

To meet the needs of the moment, Labour would have to undo Tory cuts and privatisation as a starting point. Reeves’s claim that there will be “no return to austerity” is at odds with the government’s cut to winter fuel allowance and its instruction to departments to make billions of savings.

Once again, the nationalist right’s narratives on migration are going unchallenged. Last month, Starmer visited Rome to praise Georgia Meloni – whose Fratelli d’Italia party is deeply rooted in Italy’s fascist tradition – for her “remarkable progress” in stopping small boats.

The political project now running Labour was not built to defeat the nationalist right, but partly to hammer the left. In this it succeeded, but at a cost. A wealth tax (backed by the public by 7 to 1) could be a handy alternative to austerity now. Nationalising water (backed 9 to 1) and energy companies (4 to 1) could improve the lives of millions. Confusing Corbyn’s electoral success with the validity of his policies could prove a deadly mistake.

Labour’s top brass regard the general election as an emphatic mandate for their strategy. The 33.6 percent the party received – half a million fewer votes than it got in 2019 – now looks shaky, and could look even shakier if Reform UK’s vote consolidates, one way or another, behind the Tories.

Badenoch and Jenrick represent a politics that until recently would be recognised as far right. Via either electoral success or accommodation by the Starmer government, their ideas will become a fixture of our politics. Labour’s strategists won’t be laughing for long.

Michael Chessum is a journalist and political activist based in London. This Is Only The Beginning: the making of a new left was published by Bloomsbury in 2022.