Picture the scene: Köln Opera House on a cold, wet winter’s afternoon on Friday January 24, 1975. For the first time ever, a jazz concert is due to take place in that hallowed hall, and 1,400 tickets have been sold. The promoter is a precocious, but by now extremely anxious, 18-year-old student called Vera Brandes.

The star and his record producer have just turned up in the latter’s old Renault 4 after an exhausting five-hour, 350-mile drive from Zürich. And the star is refusing to play.

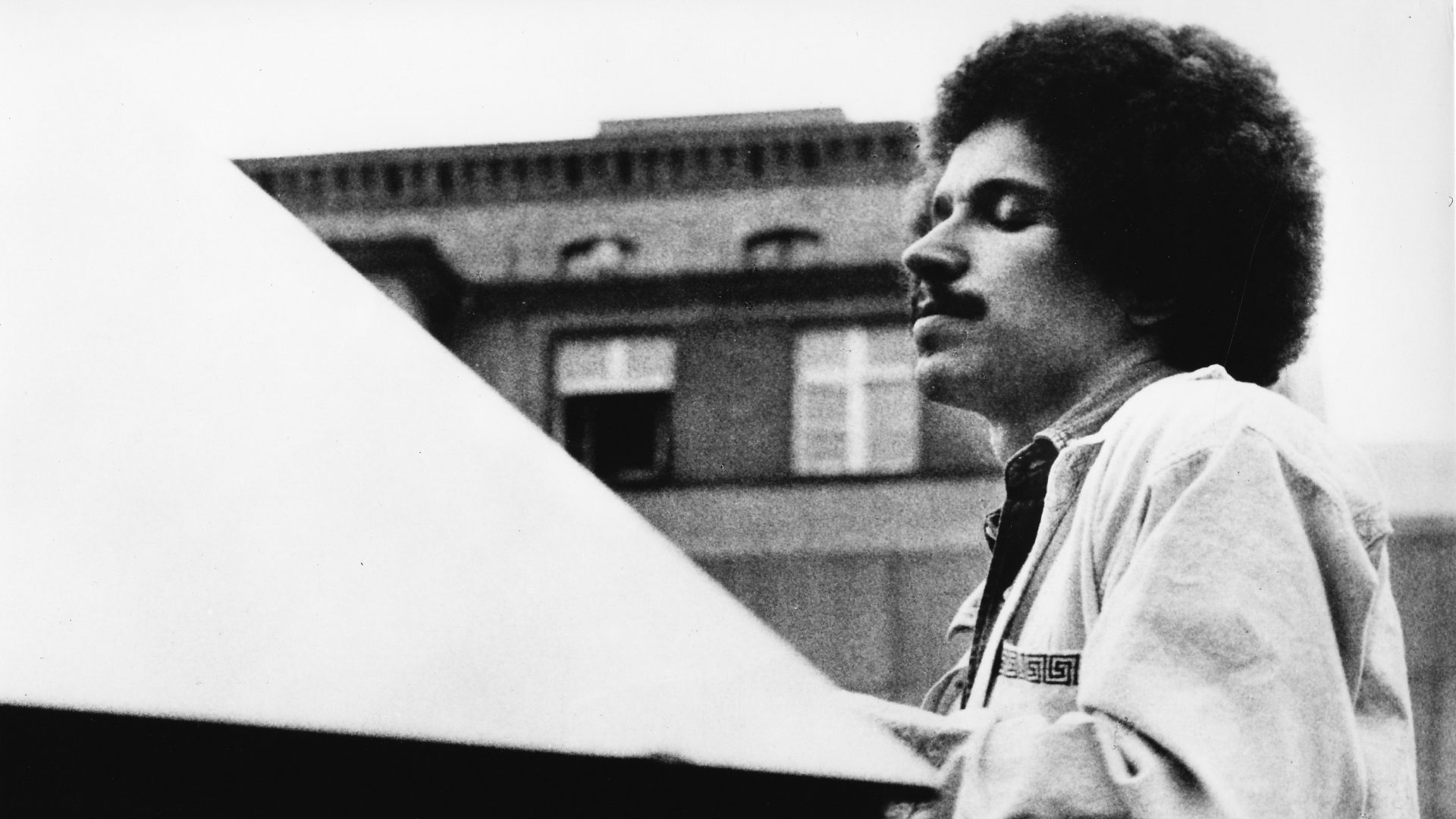

Famously fastidious and temperamental, American jazz pianist Keith Jarrett was at that time touring Europe as a solo artist. Wearing a brace due to acute back pain, which had kept him awake for several nights, Jarrett was fuming.

The concert was due to be recorded. The pianist and the producer, Manfred Eicher of ECM Records, had insisted on being provided with a Bösendorfer 290 Imperial grand piano, and were now staring in disbelief at the instrument on the stage – a Bösendorfer half grand (not a baby grand, as often reported). Worse yet, several keys were sticking, the ones at the top end were jangly, the bottom end sounded tinny, and the sustain pedal wasn’t working properly.

Years afterwards, Brandes recalled it all in nightmarish detail. “When we got to the opera, the auditorium was not lit… The only light that was on the auditorium and on the stage were tiny little green light bulbs for the emergency exits. The piano was on the stage already, and Keith played a few notes, and then Eicher played a few notes. They didn’t say anything.

“They circled the instrument several times, and then tried a few keys and said nothing. Then after a long silence Manfred came to me and said: ‘If you don’t get another piano, Keith can’t play tonight.’ And it was like I fell from the sky: ‘What do you mean? You said you wanted that Bösendorfer.’ And he said, ‘Well, not that Bösendorfer…’”

They later discovered that the Imperial had been delivered, but to the wrong location in the opera house.

This half grand was normally used only for rehearsals. No professional pianist would have agreed to use it in concert, let alone a notoriously picky one who was exhausted and in pain. On the phone, Vera managed to locate another Imperial in the city, but it soon became clear that they wouldn’t get it to the Opera House in time.

Jarrett and Eicher announced that they were going back to their hotel, and Brandes knew she had to stop them. Opening the car door, she bent down and eyeballed Jarrett, begging him to play: it was too late to refund the audience, and once they discovered the concert had been cancelled, there would be a riot.

Jarrett stared silently back at her. “Never forget,” he muttered, “only for you.”

With only a couple of hours to go, a piano tuner set to work to make the half grand as playable as possible. Meanwhile, Brandes took Jarrett and Eicher to a nearby Italian restaurant. Here, the food took an age to appear, and when it finally did, there was only time to scoff down a few mouthfuls before they had to return to the concert hall.

It was a miracle that the concert took place at all that night – even more so that the recording of it made by ECM would become the label’s most successful release ever, selling four million copies worldwide and turning Jarrett into a star way beyond the world of jazz. On the Köln Concert, what we hear is an entirely improvised solo performance, in which the pianist sticks mainly to the less defective middle register of the instrument.

Along with his sublime playing, the grunts, the cries of triumph, the foot-stomping – all these accompanying noises contribute to the sense that Jarrett is indeed spontaneously creating music out of nothing but the sweat of his brow and his own genius.

In their forthcoming film documentary Köln Tracks: the Legend of Keith Jarrett’s Köln Concert, director Vincent Duceau and screenwriter Elie Elbaz put forward an interesting idea: that it was the very constraints under which Jarrett was working that dredged up such powerful music from deep inside him. Duceau decided that the piano itself should be at the heart of the film.

“The concert became what it is, not despite the broken piano, but thanks to it. And so the documentary is also a reflection on what constraint is in art, and what it brings, because we’re convinced that this concert wouldn’t have been what it is if Keith Jarrett had played on the initial Bösendorfer Imperial that he expected to play on,” he said.

Embarking on their film, Duceau, Elbaz and their colleagues soon found themselves working under equally tough constraints. To begin with, they learned that the city archives, which might have given them some background to the story, had been destroyed 30 years earlier during the construction of Koln’s subway system. Then, they say, ECM refused to grant them the right to use the music. And Jarrett himself did not want to be interviewed.

The filmmakers also asked for interviews with Manfred Eicher and sound engineer Martin Wieland, who politely declined their requests, Eicher telling them that there had probably been too much speculation over the years. Accounts are somewhat at variance, but one thing seems beyond question: the profits from the record helped to keep ECM afloat for years afterwards.

Fortunately, the production team found other people to interview, including Brandes. “And what is interesting is that they all have different memories. A lot of myths and legends were created, and most of the stories we currently hear are not completely accurate, and this documentary is some kind of detective road movie, trying to make out what is true and what is myth,” says Duceau.

Jarrett, now aged 79, is no longer able to play the piano, having suffered two strokes in 2018. But despite his disdain for the Köln Concert, it remains his most famous and lasting achievement.

With a Kickstarter crowdfunding campaign under way this month, Köln Tracks should be complete by June 2025, with release planned for November 2025 on the 50th anniversary of the album’s release, accompanied by a special concert in Paris.