One medieval turret, stone walls, and a moat that local children use for sledging in winter are all that remain of Kaunas Castle. It was built in the 14th century on the confluence of two large rivers in a borderland constantly

overrun by invading armies. By the 19th century, Kaunas was a Russian garrison town.

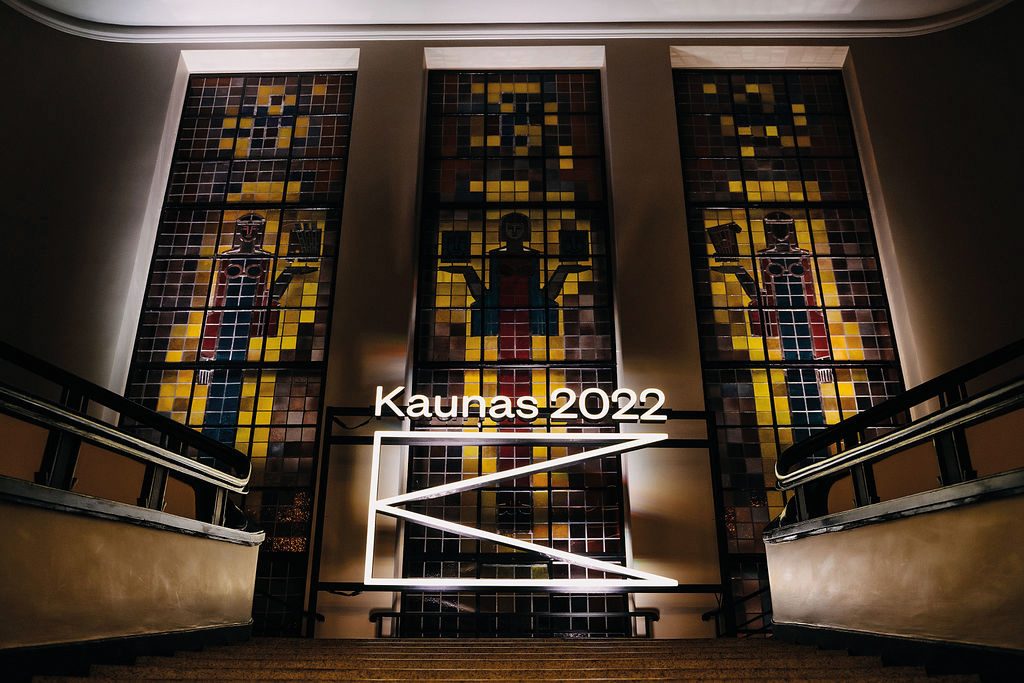

These days it is Lithuania’s second city, but it lives in the shadow of Vilnius. The capital is a one-hour journey away, but for the residents of Kaunas, the distance feels far greater. For decades it has been overlooked and forgotten, but that is changing as the city marks 2022 by becoming a European Capital of Culture with hundreds of events taking place over the course of this year.

The bid to get Capital of Culture status began almost a decade ago, when a group of art historians working at one of the local universities decided they needed to do something to stop the exodus of young people from Kaunas. Lithuania has one of the highest migration rates in the EU, driven in part by the impact of the 2008 crash. One in three Lithuanians now live overseas, 300,000 of them are in Britain. “There was an assumption that once you finished university you will leave either for Vilnius or go overseas. We wanted people to see Kaunas as a place where you have a future,” says Andrius Veršinskas from Kaunas IN. “Getting European Capital status is about the power of attraction.”

Dr Daiva Citvarienē, an early campaigner, agrees that migration was the driving issue behind the bid. “Everyone in my family, everyone in my village has left and gone overseas. It’s so sad, we have been in a long dark tunnel. The Soviets wanted to reduce us to a motorway stop-off point between Vilnius and Klaipēda” (the port city on the Baltic Sea), she says.

The striking modernist architecture that graces the city centre tells another story; of a place that once had big dreams. For a brief period between 1920 and 1940, when Vilnius was under Polish control, Kaunas was the capital of the newly independent Lithuania. This provoked a huge construction boom of government buildings, museums and universities. Six thousand modernist and Art Deco buildings were built in just 15 years, with the aim of turning Kaunas into a modern European city. But its moment in the sun was brief, ending with the second world war and the subsequent Soviet occupation. Moscow moved the administrative capital back to Vilnius and set about erasing all memories of Lithuania’s interwar independence.

Under communist rule, Kaunas became a centre for the textile industry. Brutalist concrete housing estates were built on the outskirts to house the workers. The remains of the medieval town around the castle fell into disrepair, as did the elegant modernist buildings of the interwar period. Over the past six years, there has been a great deal of restoration work done and the government has applied for Kaunas’s modernist architecture to get Unesco World Heritage status. The decision on that will be announced later this year.

But Kaunas has other, less visible scars. Before the war, a quarter of the population was Jewish; 90% of them perished in the Holocaust. Many of them were murdered in Kaunas by Lithuanian Nazi collaborators.

The ghetto in which the Jewish population was confined was burned down by the Nazis as they retreated. Thousands were shot and thrown into mass graves at the Ninth Fort, a former Tsarist barracks on the outskirts of the city. There is now a museum there and a memorial in the surrounding park.

The South African artist William Kentridge, who is of Jewish Lithuanian heritage, has a major exhibition running until November at the National Art Museum called That Which We Do Not Remember. The centrepiece is a powerful audio installation with loudspeakers playing a soulful lament by South African choral singers set against the theatrical backdrop of an abandoned Jewish cemetery made with paper cut-outs.

“They are songs of comfort from South African choirs to Lithuania,” says the artist. “But they’re also saying thank you. All of those members of my family who stayed behind are dead.” His great grandparents sailed from Lithuania to Cape Town in 1900 and anglicised the family name from Kanterovich to Kentridge.

“I’m interested in countries with complicated histories. Lithuania must deal with its history of collaboration. South Africa also has a shameful past,” says Kentridge. “I’m aware of the privilege we had as whites in South Africa, but also that it was a place that gave us refuge.”

There are several other famous names in the Kaunas 2022 programme, including the performance artist Marina Abramović and Yoko Ono, who also has a Lithuanian connection. She worked with George Maciunas, founder of the avant-garde art movement Fluxus that emerged in the late 1950s. Ono has an installation in the courtyard of the former Central Bank. Titled Ex-It, the work consists of 100 coffins containing living fruit trees and loudspeakers playing birdsong. It feels resonant in the wake of the pandemic, but it could also be a metaphor for climate change, or a warning, given current geopolitical tensions. Belarus and Ukraine are in the neighbourhood and the Lithuanians feel the tension.

In the past three years, a number of young professionals and tech start-ups have moved to Kaunas from Belarus and Ukraine. Brexit, coupled with the pandemic, has prompted some Lithuanians to return home from the UK. New jobs are being created, with the biggest growth coming from IT and advertising. But young tech creatives want to live in cities that provide leisure in the form of art, culture, green spaces, cafes, bars and restaurants – which is where money for the European Capital of Culture is being invested.

I spent a happy morning walking around photographing murals. Kaunas City Council has set up a scheme called Living Walls that connects professional artists and property owners. It operates like the Tinder dating app. An artist can swipe for an appropriate wall and the city will finance them to paint it. There are now around 100 murals in the city centre. Some of them consist of huge photographs of Jewish families from the interwar period that have been blown up and transferred on to walls.

Rytis Zemkauskas, one of the curators of the 2022 programme, says many of the events are inspired by “our collective memory, successive waves of trauma, occupations followed by statehood, followed by occupation. We have things we have chosen to forget that so many of our citizens were killed and that some of our citizens were killers”. Part of the work over the past five years has been establishing a “memory office” of historians and archivists to collect stories and publish them. “It was a difficult process. There was anger on social media. People asked why are you bringing this up? Others said I don’t believe these Jewish stories. It’s been like touching a nerve.”

In May the entire city will be turned into a stage with a programme inspired by the events of 1972, when the citizens of Kaunas revolted against Soviet occupation. It began with a long-haired 19-year-old schoolboy called Romas Kalanta setting himself on fire, shouting “Freedom for Lithuania”. He died later in hospital. Thousands gathered for his funeral, which turned into a huge protest. Many of them were photographed by the secret police and punished. The communist authorities also clamped down on the local theatre scene, arresting a well-known director and shutting down a popular mime group. The Soviets began to see any form of culture as a threat.

Another form of resistance under the Soviet occupation was basketball. The first match in Lithuania took place 100 years ago in Kaunas. Under communism, the Lithuanians consistently beat the Red Army team in matches that united the entire country. Cheering their national team became an expression of protest. These days the country continues to produce international players. Kaunas has built a House of Basketball with a

restaurant, museum and exhibition space, which will host a number of events in the coming year.

So will all this investment pay off? The European City of Culture idea was started in 1985 by Melina Mercouri, the Greek actress, singer and politician who believed that culture was not given the same attention within the EU

as politics and economics. Athens was the first titleholder and Glasgow was

the first British city to get it, in 1990, with the slogan “Glasgow’s miles better”. Two large studies have investigated the impact of the scheme over the course of the last 30 years and the results are positive. On average, becoming a Capital of Culture raises the GDP of a region by 4.5% and the

impact can still be felt many years later. These results stand in sharp contrast to the hosting of mega-events such as the Olympics, which in many cases have had a negative impact on the public purse.

As a young reporter, I visited Glasgow as it prepared for European Capital of Culture status and I recall the sense of pride people felt seeing their city regenerated. Thirty years on, Glasgow’s reputation has been transformed from a depressed post-industrial city that lived in Edinburgh’s shadow to an attractive place for young people to live, with a vibrant arts scene. The title also turned Glasgow into a city capable of hosting large-scale events such as the 2014 Commonwealth Games and Cop26.

Kaunas is one of three European cities holding the European Capital of Culture title in 2022, along with Novi Sad in Serbia and Esch-sur-Alzette in

Luxembourg. All three will be hoping that, like Glasgow, their cities will become places where young people wish to stay and make a life for

themselves rather than going to seek their fortunes elsewhere. And if the tourists follow, so much the better.