In February 1945, with the second world war entering its final weeks, a 16-year-old trainee teacher named Karlheinz Stockhausen stood on the station

platform at Altenberg, just south of Dresden, and bade farewell to his father.

It was the first time Karlheinz had been home for quite a while since leaving for a residential college in Xanten in 1943. Mostly he spent his student holidays working as a firewatcher, looking up as wave upon wave of allied bombers lumbered overhead before the horizon began to flicker and glow orange as Dortmund and Düsseldorf burned.

Too young for the draft, in 1944 he was transferred to a school in Bedburg, west of Cologne, that was pressed into use as a field hospital. The music student became a medical orderly and stretcher bearer, tending to horrifically disfigured victims of phosphorous bombs and piling up corpses in a chapel awaiting burial.

Simon Stockhausen had embraced Nazism with an enthusiasm that sickened his son. Karlheinz hid his distaste of the Wehrmacht officer’s uniform and watched the approaching train taking his father back to the front with a mixture of relief and deep-lying filial anxiety. Simon, knowing the war was lost, knowing exactly what he’d been part of, put down his kit bag, shook his

son’s hand, held on to it for a moment and looked him in the eye.

“I’m not coming back,” he said. “Look after things.”

It’s no surprise that Karlheinz Stockhausen, groundbreaking composer, was always looking forward. He was desperate to reach the future, to put as much distance between himself and the trauma of the war as he could.

His mother, Gertrud, had suffered from acute depression and when she attempted suicide in 1932 she was placed in an institution. Stockhausen always remembered the night a man “with a red cross and a white cockade” took her away. He was four years old.

Nine years later, in 1941, the still-institutionalised Gertrud Stockhausen

was murdered in the extermination camp at Halador as part of the Nazis’

euthanasia programme directed against the weak and infirm.

Small wonder that the musical young boy turned into one of the most

innovative and adventurous composers of the modern era, a man seeking to

hasten the future to quicker escape the past, who forged new techniques that

smashed through the boundaries of musical form and tradition. He would

even cite the military marching songs played constantly on the radio during his childhood as a catalyst for rejecting such regular rhythms in his music.

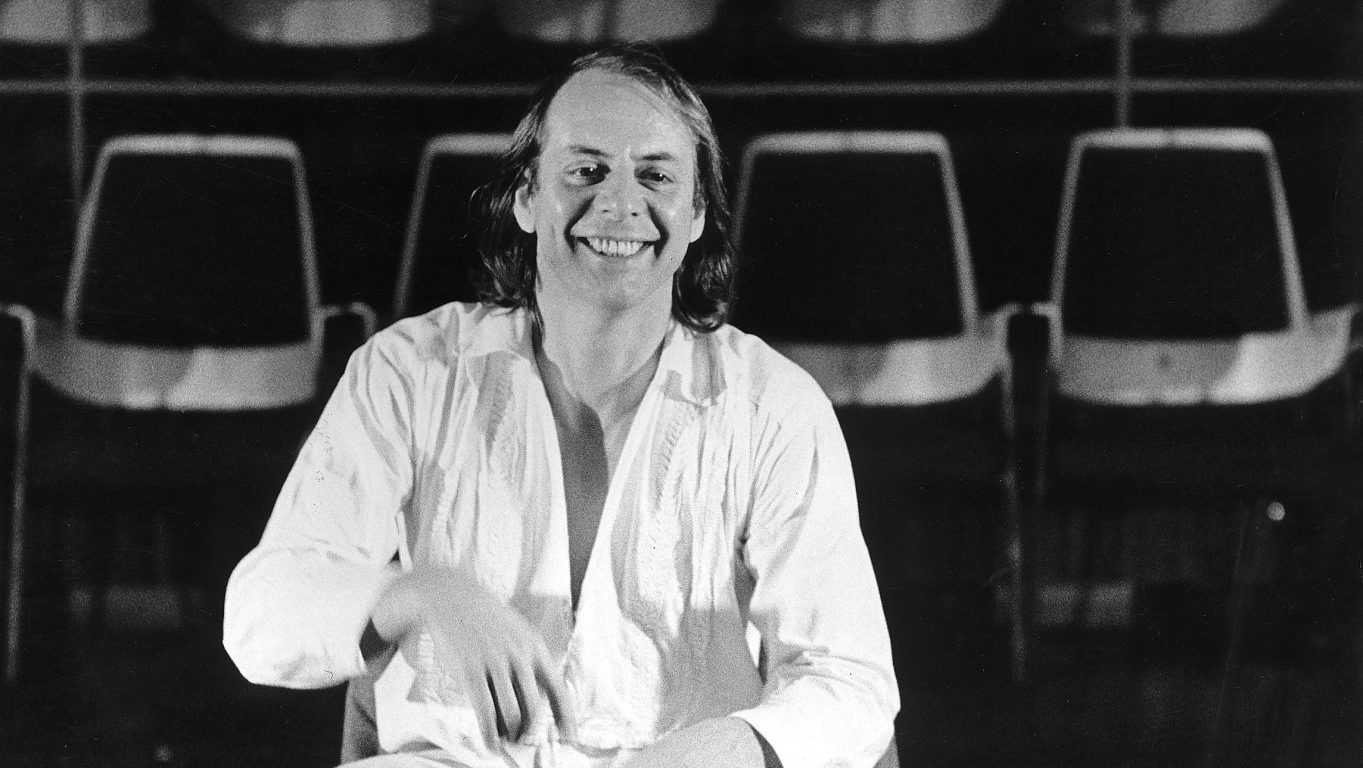

In the late 1960s he invented a spectacular new origin story, that he had been born to God on the distant star Sirius where he also received his musical education, and began dressing all in white as if pitching himself as the antithesis of the regime that destroyed his family and his country.

Miles Davis, David Bowie, Laurie Anderson, Kraftwerk, Pink Floyd, Neu!, Frank Zappa and Brian Eno would all cite Stockhausen as an influence. The

Finnish conductor Esa-Pekka Salonen called him “the rock star of my youth”

and the Beatles put him on the cover of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, in the back row peeping out from behind WC Fields. Stockhausen’s two-hour

experimental piece Hymnen, a work that used national anthems, spoken words, repetition of the number nine and snippets of audio recorded from shortwave radio – a source Stockhausen called “instant electronic music” – to create a remarkable soundscape, was a direct influence on the Beatles’ own venture into the avant-garde, Revolution 9, on the “White Album”.

“His influence has been enormous,” said Pierre Boulez in 2001. “He invented

a new kind of relationship between music’s components and has changed our view of musical time and form.”

Stockhausen’s music and flamboyant presence were not to everyone’s taste –

Roger Scruton dismissed him as “not so much an emperor with no clothing but a splendid set of clothes with no emperor” – but his effect on 20th-century music spread to all parts; jazz, classical, pop, electronic, psychedelia and rock. His music was as much at home in the concert hall as the late-night psychedelic happening.

When Karlheinz harnessed electricity into sound and showed the rest of us, he sparked off a sun that is still burning and will glow for a long time,” said Björk.

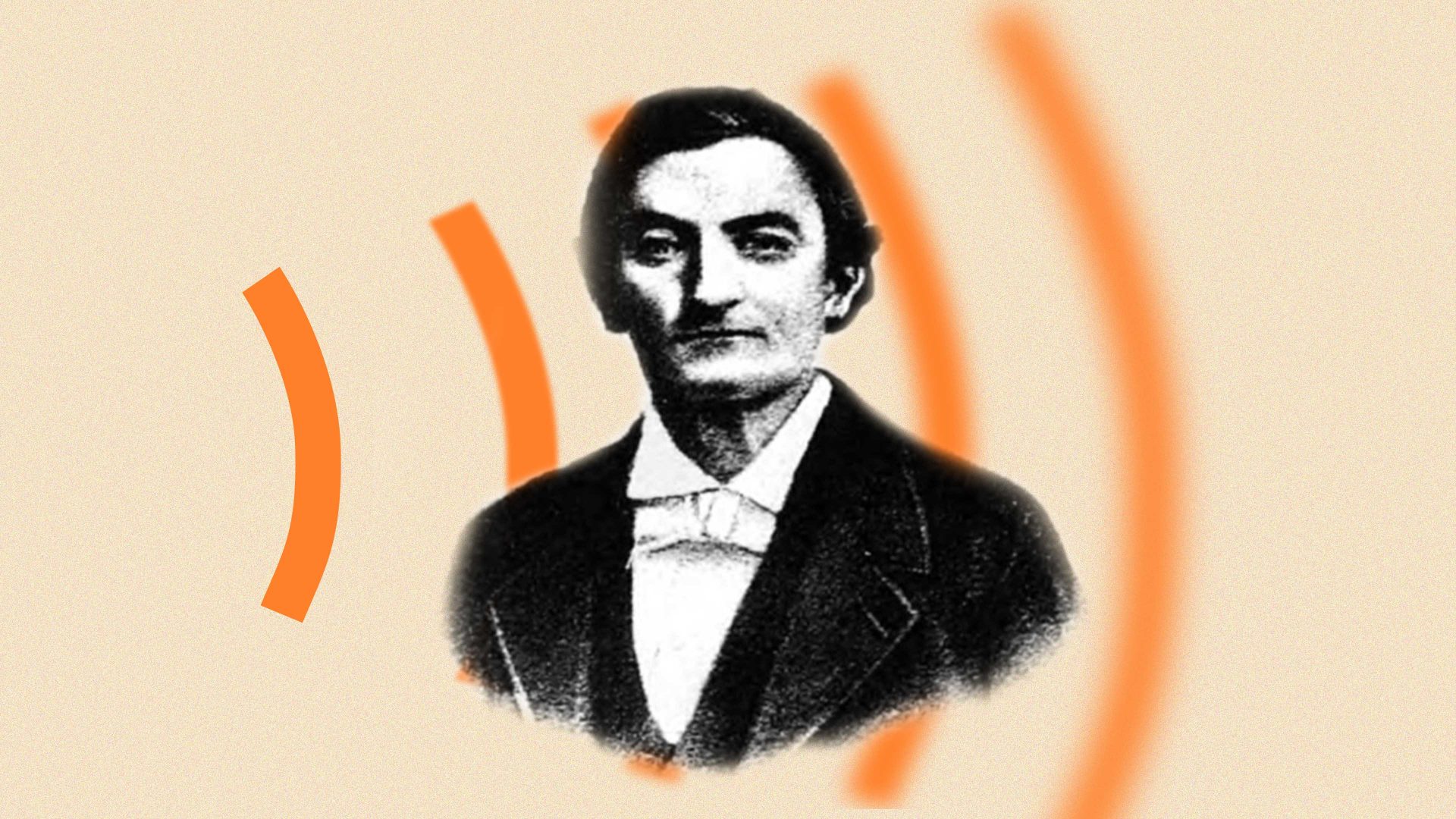

The moment that ignited that sun and fixed Stockhausen’s musical destiny

came five years after he’d waved off his father to his death on the Hungarian front. After the war he resumed teacher training and music studies at the conservatoire in Cologne, where he studied composition and piano, developing a keen interest in the atonality pioneered by Arnold Schoenberg and the Second Viennese School.

Summers were spent at the annual contemporary music festival in Darmstadt, where in 1950 Stockhausen heard Olivier Messiaen’s Quatre Études de rythme for the first time, of which the second movement Mode de valeurs et d’intensités was an epiphany. “Incredible star music” he called it, a piece that launched atonality beyond the 12 notes of the chromatic scale and into intricate serialisations that went beyond conventional pitch. Stockhausen’s first composition, Kreuzspiel, soon followed, premiering at Darmstadt the following year and, according to the composer, nearly provoking a riot with its modal dissonance and bold experimentation with pitch, time and rhythm.

By the mid-1960s he was energised by the possibilities of new musical technology and forged ahead into electronic sound, creating music by

splicing tape as much as using traditional instruments.

Having reinvented himself as a son of Sirius in the mid-1970s, Stockhausen

began work on what he regarded as his masterpiece, the extraordinary 29-hour opera cycle Licht that made Wagner’s Ring seem like the Beach Boys.

Comprising seven operas, one for each day of the week, Licht brims with

invention while walking a fine line between experimentation and self-indulgence. In one part of the cycle the orchestra is seated in the shape of a face. In another, orchestras play simultaneously in different auditoriums.

All seven operas, all 29 hours, are based around what Stockhausen termed

a “superformula” comprising just 19 bars of music that, played together, last less than a minute.

For all his musical invention and often controversial pronouncements – in 2001 he was forced to apologise for calling the World Trade Centre attacks “the greatest work of art possible in the whole cosmos” – from his early conventional atonality to the overblown theatrics of Licht, Stockhausen sought to prove his conviction that “the highest calling of mankind can only be to become a musician in the most profound sense; to conceive and shape the world musically”. This was something he’d learned from his wartime reading of Herman Hesse’s The Glass Bead Game as a teenager, a book that presents a future where the most profound music is born out of a combination of ritualised games, mathematics and philosophy.

He would spend a lifetime seeking to reach that future, a creative place as far as possible from the vivid horrors of his past.