At 8.30pm on October 25 1946, in a room misting with cigarette smoke in the Gibbs Buildings of King’s College, Cambridge, around 30 people, all men, all dressed in tweed jackets and flannels, sat facing two empty armchairs by the fireplace waiting for the weekly meeting of the Cambridge Moral Sciences Club to begin. These gatherings usually attracted barely half that number but this week promised something a bit special.

The meetings tended to follow the same pattern: a guest speaker would present for debate a philosophical argument that the chairman of the club, Ludwig Wittgenstein, one of the leading philosophical minds of the 20th century, would prove was not an argument at all, just a failure of the language in which it had been presented.

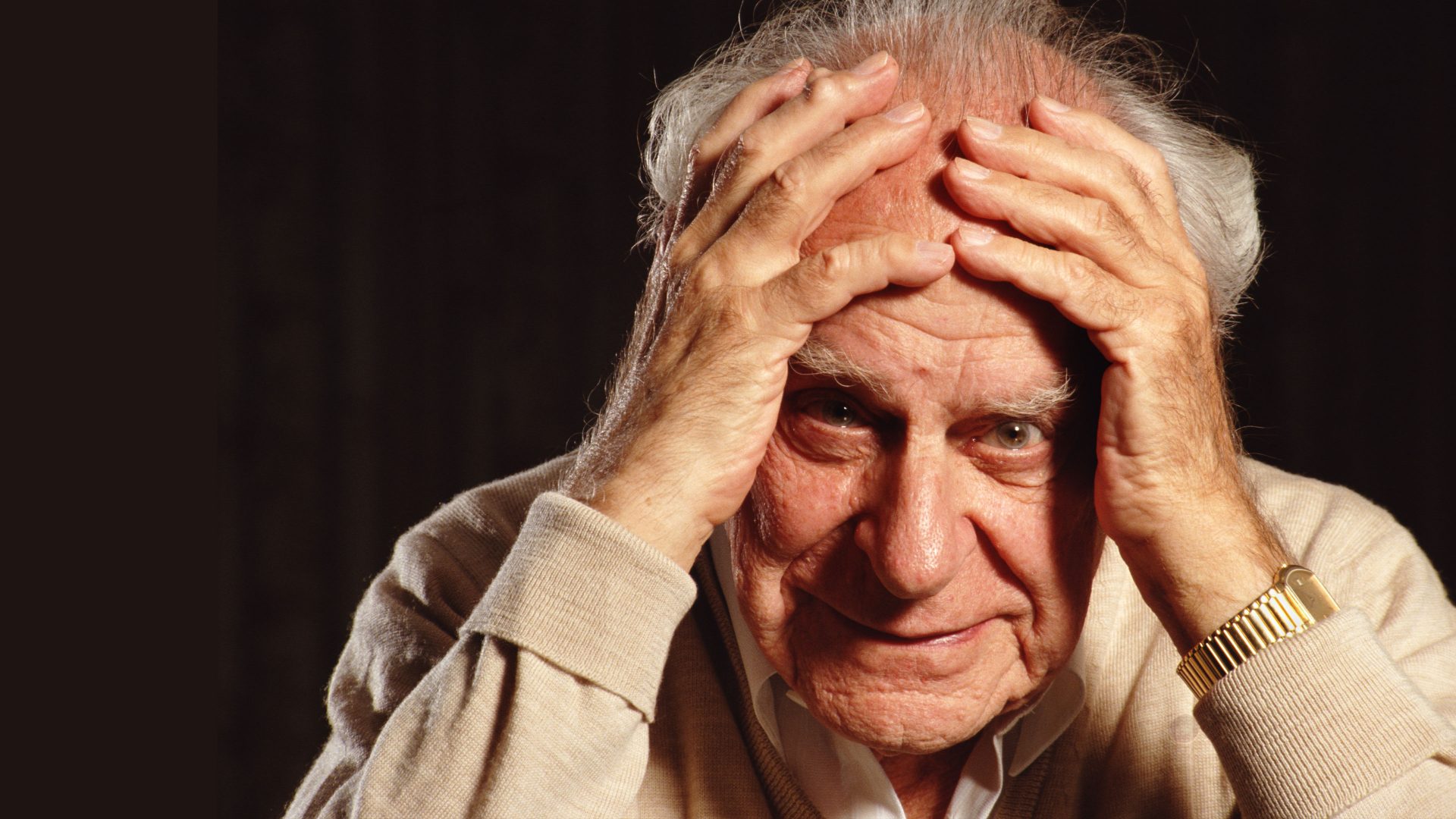

That autumn night the guest speaker was Karl Popper, a Viennese newly arrived in Britain as a reader in logic and scientific method at the London School of Economics, who had spent the war years in New Zealand after leaving Austria ahead of the 1938 Anschluss. Popper was making a name for himself thanks to his book The Open Society and its Enemies, a comprehensive philosophical demolition of totalitarian states and regimes that he’d begun on the day Germany invaded Austria. It would prove prescient – the cold war was already beginning to chill relations between east and west, even as Popper arrived in Britain.

The book caused a stir in academic circles, not least for its strong criticism of philosophers, particularly Hegel and Plato, hence the heightened anticipation surrounding its author’s locking of horns with Wittgenstein. It would turn out to be a memorable evening, but possibly not for the reasons attendees might have anticipated.

Born into the Viennese intelligentsia with a lawyer father and a philosopher for an uncle, Popper grew up surrounded by his father’s library of 14,000 books. He left school at 16 thanks to the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian empire, but educated himself by attending university lectures in Vienna, taking part in intellectual discussions in Ringstrasse cafes and joining the Marxist Social Democratic Workers’ Party. He would go on to become a prominent critic of Marxism.

Popper qualified as a cabinet maker and had ambitions to be a schoolteacher before completing a doctorate in psychology in 1928 and commencing research on what would become The Logic of Scientific Discovery, published in 1934.

The book tackled the issue that would define Popper’s career: the difference between scientific knowledge and what he saw as the baseless rhetoric expressed by the likes of Freud and Marx. He argued that the laws of science are not based on the principle of verification, but of “falsifiability”. Theories like those employed by Freud in the field of psychoanalysis were too woolly to be properly debunked, Popper wrote,

whereas Einstein’s theory of relativity, for example, being grounded in fact, could in principle be disproved. This vulnerability to contradiction reinforced for Popper the superiority of science over metaphysical fields, from Marxism to astrology.

His Jewish background led Popper to leave Austria ahead of the inevitable German invasion. With his wife Josefine he sailed in 1937 for an academic posting in New Zealand where he wrote The Open Society and its Enemies, arguing that history has no hard and fast laws and is always changing, making planned societies, most notably in fascist and communist states, unviable without violence and oppression. “Instead of posing as prophets,” he wrote, “we must become the makers of our own fate.”

For Popper a truly open society was one that accepted change and recognised the opinions and choices of its inhabitants. Ignorance of a society’s flaws was no excuse; he never allowed or accepted the idea that people did not know about the Holocaust or the gulags, rather they chose not to know. Knowledge, he said, was a moral obligation.

The Open Society was fresh, opinionated and iconoclastic, dismissing Plato, Hegel and also Marx as “nauseating”, “idiotic”, “illiterate” and “imbecilic”. Distancing himself from mainstream thinking made Popper a perennial antagonist, a “pugilistic refutation machine” in the words of one obituarist. He revelled in the role, writing of how “philosophers are characterised by their pretentious wisdom; their arrogation of knowledge which they present to us with a minimum of rational or critical argument”. This guaranteed a full house for his debate with Wittgenstein. As it turned out, the encounter lasted barely ten minutes.

The history of philosophy is strewn with progressive minds who were contemporaneous with equally brilliant nemeses – Plato and Aristotle, Bacon and Descartes, Kant and Hegel. Yet rarely did two genuinely great thinkers actually face each other across a debating chamber. Epoch defining the occasion might have been, but nobody, not even those who were there – including Bertrand Russell – could agree on exactly what happened. It’s undisputed that Wittgenstein stormed out of the room and a poker from the fireplace was involved, but beyond that, nearly every version of the story differs.

According to Popper’s autobiography the two notoriously irascible figures immediately began disagreeing vehemently over the fundamental nature of philosophy. Before long Wittgenstein had picked up a poker from the fireplace and was waving it “like a conductor’s baton to emphasise his assertions”. When he challenged his guest to come up with an example of a moral rule, Popper replied: “Not to threaten visiting lecturers with pokers!”

Wittgenstein, in Popper’s account, immediately flung the poker to the ground and stormed out, gown flying, slamming the door behind him.

The fallout from the encounter has lasted for decades and has even spawned entire books dedicated to those ten stormy minutes in a shabby, stuffy college room in Cambridge. Whatever really happened, it was enough to seal Popper’s reputation as a major figure in modern thought and within two years he was elevated to a professorship at the LSE, where he packed out lecture halls for the rest of his career.

A complex man, Popper’s advocacy of the fallibility of true knowledge did not usually extend to his own and he didn’t always respond graciously when presented with counters to his arguments. He was quick to accuse others of plagiarism and, according to one biographer, “remained to the end a spoiled child who threw temper tantrums when he did not get his way”.

Despite his flaws, Popper’s work gained new traction during the fall of communism, with Ryszard Kapuściński later recalling: “Those books came as a revelation to us and to intellectuals and dissidents throughout eastern Europe. The views they expressed were as great a source of comfort as the authorities feared. Above all else, they taught us to be critical”.

For all he came to be feted by the political right – Margaret Thatcher was a disciple – Popper was never an advocate of an unbridled free market. While wary and critical of big government, he espoused tolerance as a fundamental principle of an open society and was in favour of centralised social institutions that protected the economically vulnerable.

“If there could be such a thing as socialism combined with individual liberty,” he said, “I would still be a socialist.”